Red Star Rogue (12 page)

Authors: Kenneth Sewell

MARCH 5 (Day Twelve)

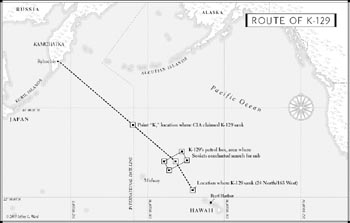

There is now no doubt that the submarine has departed from a routine mission schedule. For the second time K-129 fails to send a scheduled report to fleet headquarters. This signal is the mandatory announcement that the missile boat is on station and patrolling in range of its assigned target.

The submarine is checking its baffles more frequently now. On occasion, it rises and sinks through the ocean thermoclines, trying to catch any trailing American attack sub off its guard.

K-129 is traveling a course that lies between two converging seamount chains. To the northeast lies the Musicians Seamount, one of the largest collections of underwater mountains in all the oceans. Here are submerged massifs bearing such names as Hammerstein, Mahler, Rachmaninoff, Paganini, Ravel, Haydn, Chopin, and Mendelssohn. To the southeast lies the Hawaiian Ridge.

Sonar contacts from shipping and fishing activity are frequent. Surface vessels are identified by their unique sounds as freighters, tankers, and the occasional American warship (destroyers or light cruisers traveling fast out of Pearl Harbor for Southeast Asia, Japan, or Korea).

K-129 has traveled approximately 2,309 nautical miles.

MARCH 6 (Day Thirteen)

K-129 rigs for silent running, engaging its single electric auxiliary motor. It creeps along at two knots. All unnecessary equipment is secured. By late in the day, the sub is approximately seventy miles north of the Hawaiian Leeward Islands. To the east lies the western edge of Blackfin Ridge, a long, narrow, and steep plateau that runs east to west in the Northern Hawaiian Seamounts. K-129 frequently checks for trailers, often changing depth and course.

The submarine has traveled a total 2,363 nautical miles.

MARCH 7 (Day Fourteen)

The submarine is quiet as it continues slowly toward its secret destination. The air in the boat is becoming stale. Cruising at two knots draws a minimum of power from the massive batteries, extending the time between snorkeling cycles and the intake of fresh air.

On the surface, five hundred feet above, a beautiful sunset ends the tropical day. Below, in the darkness, men hurry about their tasks, readying the submarine for its mission. During the night, the order is finally given to surface the submarine.

K-129 has traveled approximately 2,396 nautical miles.

Exactly what occurred aboard K-129 after sailing from Rybachiy Naval Base can never be known to a certainty, unless American intelligence officials recovered written documents from the wreck and someday declassify them for public release. But an examination of what can be pieced together about the final journey reveals at least three major clues that something indeed went terribly awry aboard the submarine. First, the K-129 missed sending a routine, but expected, message to fleet headquarters that it had safely crossed the International Date Line on March 1. Then, on March 4, the eleventh day of the voyage, K-129 trespassed outside the boundary of its normal mission box and proceeded on a dangerous course that would take it closer to enemy waters than a normal assignment allowed. Finally, on March 7, a more ominous harbinger of trouble came with the submarine’s failure to transmit the mandatory message to headquarters that it was on regular station and prepared to carry out its patrol.

It is also known that the submarine’s commanders, Captains Kobzar and Zhuravin, in their long careers in the Soviet submarine service, had never before failed to follow all procedures to the letter. The K-129’s

zampolit,

Captain Lobas, who was central to any decision to divert from an assigned mission, likewise had always been a model of Communist discipline. Yet these key command officers aboard K-129 did not follow standard procedures, whether by choice, coercion, or incapacitation.

Had K-129 been seized while en route to the mission box? The inexplicable presence of the extra men who were placed aboard the submarine a short time before sailing takes on new significance when the missed radio communications and deviant maneuvers of the boat are considered.

Later, the presence of these strange crew members became a key part of the mystery of K-129. Had these mysterious figures taken over the submarine? If so, was the takeover an outright mutiny? Or was control usurped with convincing orders from some higher command? In the latter case, these bogus orders would have had to originate in Moscow, because admirals of the Pacific Fleet and Kamchatka Flotilla later claimed they had no knowledge that K-129’s mission was anything other than a regular combat patrol.

By the end of March 5, K-129 had sailed out of its regular patrol box and was heading toward Oahu Island, Hawaii. With no indication that orders for a special mission had been given by fleet headquarters, and failure to transmit periodic and mandatory radio signals to home base, the submarine had become a rogue boat.

Another baffling fact about K-129’s journey is the absence of reaction to its aberrant behavior. At that moment, no one in either the Soviet fleet headquarters in Vladivostok or the U.S. Navy Pacific Fleet headquarters at Pearl Harbor raised the slightest concern over the missed signals or the deviation from course. It seems that K-129 had slipped through the cracks in the security systems of both navies.

The only sign that something terrible had happened aboard K-129 was not in the form of hard evidence at all, but rather in the premonition of a person thousands of miles away, on the other side of the Date Line, at Vladivostok.

Irina Zhuravina, wife of the submarine’s deputy commander, had taken their young son, Misha, to her office at the Ministry of Economics. It was March 8 in Vladivostok (March 7 in Hawaii) and one of the most festive days in Soviet society—International Women’s Day. This was the day the Russian-style socialist system honored the role of women in the proletarian revolution. The office party was filled with celebrating professional women, most with their children. Irina was feeling especially good, with the party taking her mind off the troubling departure of her husband two weeks before.

Years later, Irina recalled what happened next, and despite the cynical realism that came with her Communist education, claimed that she experienced a once-in-a-lifetime, extrasensory perception of doom.

“I know exactly the day and the hour they died,” Irina Zhuravina said. “We were celebrating International Women’s Day at work. I was there with my son, and we were having a good time. All of a sudden, I went into hysterics. I broke down, went crazy—I didn’t know what was happening to me.”

Irina’s coworkers put her in a car and drove her home. Several friends remained with her throughout the night, but she was inconsolable. The following day she quit her job, left Misha with her mother, and took the next available flight to Kamchatka and the Rybachiy Naval Base.

The submarine was not due to return to port for another two months. No word that anything was awry with K-129 had been received by any of the other wives of the submarine’s crew. Irina could not explain her overwhelming grief and physical breakdown to the families she stayed with near the base. She recalled that the friends and wives of the sub’s officers stayed up with her, looked after her.

“My friends did not leave my side, day or night,” she said. “They were always with me. What the other wives thought about it, I do not know.”

Irina was eventually told by Soviet navy officials that her husband’s submarine had been lost on the very day she experienced her premonition. As odd as it seems, Irina’s foreboding may have coincided with real events aboard the submarine.

S

OVIET SUBMARINE COMMANDERS

needed to become as adept at circumventing the Americans’ superiority in antisubmarine detection technology as they were at compensating for the flaws built into their own equipment. Veteran captains had learned a few tricks to help even the odds.

The ocean contains layers of water with different temperatures and salinity called thermoclines. Using sonar or other acoustical gear in one layer to detect a target submarine in another layer could be difficult. The layers act like screens, deflecting noise that might otherwise be picked up hundreds of miles away. Soviet submariners learned to use the thermoclines as audio camouflage by skimming from one layer to another, then cutting their engines to “ultraquiet.” By drifting silently through a new layer, a Soviet submarine could also increase its chances of detecting any U.S. sub lurking in the area.

By March 6, K-129 was nearing the end of its journey. It made the last leg entirely on its auxiliary electric motor. With the sub in this silent mode, Americans monitoring the SOSUS listening devices were having difficulty tracking the submarine as it left its normal mission box.

K-129 continued slowly until late into the night on a direct course toward Pearl Harbor at a speed of two knots. To avoid being followed, the boat’s operators swung to starboard, then to port, allowing the butterfly pattern of its sonar to bear on the blind spot directly aft of the boat. The sonar detected nothing.

On March 7, fourteen days after sailing from Rybachiy, the Soviet submarine arrived at an area north of the Hawaiian Ridge. To the east was the westernmost edge of Blackfin Ridge. Still moving at approximately two knots, the submarine neared its final destination, just to the north of 24° N latitude and 163° W longitude. It had traveled a total distance of 2,396 nautical miles since leaving the base on February 24.

In the dead of night, this mechanical predator prowled six hundred feet beneath the surface of the North Pacific, unseen and unheard by its prey. It moved at a deceptively slow speed toward an exact confluence of invisible lines appearing only on a navigational chart. The boat’s destination had neither name nor tangible features. It was, however, a fateful place in the vast sea that was to take on huge significance in the grand schemes of the Cold War superpowers.

K-129 was longer than an American football field and weighed more than six million pounds. Despite its mass, the high torque of its 180-horsepower, silent electric motor connected to a single five-blade propeller was more than enough to push the submarine smoothly through the water. The deliberate, unhurried forward momentum seemed almost leisurely, but whoever was in command of the boat was determined to reach a specific destination at an appointed time, without being detected.

No visible land above sea level lay in its path for more than three hundred miles. The submarine was maneuvering at its most efficient operational depth above a broad, deep plain more than three miles below. It could have safely dived a couple of hundred feet deeper if an enemy challenged. But there was no need to put such strain on the pressure hull, since there appeared to be no other warships of any navy for miles around.

The submarine’s charts revealed that the only terrain breaking the monotonous sea floor ahead was a pearl-like string of submerged islets known as the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and called the Leewards by local mariners. Two of these, Nihoa and Necker islands, lay less than seventy-five miles to the south. Rock masses formed the islets’ subterranean bases, making them natural barriers between the submarine and the main islands of Hawaii to the southeast. These submerged islets were only a marker on the boat’s charted course—they were not its destination.

K-129 moved forward as silently as a living sea creature, until suddenly the boat’s commanding officer broke the carefully maintained quiet with an order:

Prepare to surface.

That order, barked over the intercom, pierced every compartment of the submarine and every heart of the ninety-eight men aboard.

The steps required to surface a diesel submarine, which had not changed in the navies of the world since the beginning of the century, were certainly followed by whoever was in control of K-129 on that fateful day.

The man giving the order stood at a chart table in the control center in sweat-streaked, navy-blue coveralls. With the submarine now sailing in tropical waters, it was miserably hot in the confining vessel.

It took only a matter of minutes for the crew to begin bringing the boat up from its cruising depth to a precautionary position. The boat commander directed the helmsman to level off just below the surface, at a depth of thirty-two feet. The officer in charge and a designated deputy scampered up the steel rungs of a ladder from the control room into the attack center in the conning tower, where periscope monitors were housed. On the way up, the officer ordered the ESM mast and navigational equipment antennas deployed, but only passive systems would be used. If K-129 turned on its active radar systems, the Americans could immediately identify the submarine as a Soviet and pinpoint its location.

An antenna was raised to receive radio-navigational signals. The submarine’s destination had been carefully chosen. It was located along the most direct route from a Chinese navy base to Pearl Harbor and deliberately positioned at a precise intersection of longitude and latitude.

In the general area where K-129 maneuvered, four signal pairs of Loran-C coordinates also intersected. The navigator had four direct radio-navigation signals to verify his location, thus making it relatively easy to plot a target for the submarine’s missiles.

By 1968, Soviet submarines in the Pacific were equipped with Loran-C and Omega radio-navigation receivers. With this much data coming into the command center, it did not require a navigator with advanced skills at working out complicated formulas to get an accurate fix on a target within the approximate eight-hundred-mile range of the boat’s Serb missiles.

The advanced missile fire-control system, installed when K-129 was upgraded to a Golf II, allowed the submarine to target and launch its missiles accurately while traveling at low speeds, and without having to pause at an exact intersection of latitude and longitude. The older-model Golf I submarines, like the ones in the Chinese navy, still relied on earlier navigational systems. They

did

have to be positioned at exact longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates to accurately target their missiles.

As K-129 cruised just beneath the surface, the two officers in the action center above the control room scanned the dark horizons through the attack periscope and the navigational periscope. The officer on the navigational periscope elevated the instrument to search the night skies for antisubmarine aircraft. The periscopes visually confirmed the reports by the electronic receivers and passive sonar: The boat was alone in that vast, empty part of the Pacific Ocean.

The senior officer was satisfied by his personal reconnoitering of the waters immediately surrounding the conning tower. He slapped shut the handles of the periscope and slid down the ladder to return to the control center. Only the top edges of the fin were protruding above the surface at that point.

The next order was to “full surface,” which, when relayed to the engine control room, created a stir of activity. Two crewmen began systematically turning levers to blow ballast tanks with compressed exhaust air from stored cylinders. Normally, K-129 would start up its massive diesel engines and use the exhaust to blow the ballast tanks. The precious reserve of compressed air was hoarded for emergency use. Since, to avoid detection, the commander had not started the diesel engines, the compressed air was the only source of pressure to force water from the ballast tanks and provide the buoyancy needed to surface.

The boat’s bow broke the surface, rising in a geyser of sea foam. Before completely surfacing, the officer in charge had ordered the crew to prepare everything for an emergency dive. The commander would have had another reason not to engage the big diesel engines. He probably planned to spend only a few minutes on the surface, to avoid a retaliatory strike by any American ASW craft in the area.

Since the diesels were not being used, the sweltering crew had to wait for the cherished first blast of fresh air the diesels usually sucked into the boat through the snorkel tube.

The wait for fresh air was not long. Once the submarine was riding smoothly on the surface, the duty officer and a sailor wearing an officer’s storm raglan sheepskin jacket, quilted pants, and heavy fleece-lined boots scaled the last ladder through the conning tower to open the hatch leading from the action center to the bridge. Some residual seawater sloshing on the bridge floor always poured through the opening into the living space. The splash of cold water dripping down two levels was a minor discomfort. To the men in the control room, after two weeks submerged in increasingly foul air, the rush of clean ocean air was exhilarating.

The dozens of officers and crewmen confined behind the guarded hatch separating the control room from the forward two compartments could not have felt the splash of fresh air. Even if they had, their anger or fear would have eclipsed any feeling of relief. After the intention of their captors had become clear from the staccato orders crackling over the intercom, a state of near-bedlam must have raged in the tightly packed compartments one and two.

These veteran submariners knew, from years of missile-launch drills, exactly what such deadly orders portended. The senior seaman and officers could also estimate from time elapsed, direction of turns, and speed of the boat, that their commandeered craft was dangerously close to the huge naval base at Pearl Harbor.

Soviet men who, just days before, might never have dared display any hint of religious feeling came to that place nearly all men in combat confront at such a time. Some likely prayed aloud, without regard for what their comrades would think. Those who had sailed away leaving wives, children, and sweethearts near the bases that would now most likely become ground zero for American retaliation would have loudly lamented the fate of their loved ones.

If K-129’s top officers remained true to their rigorous naval academy training, they kept cooler heads and tried to maintain discipline, as long as there was any chance to change the situation unfolding on the other side of the metal bulkhead from their improvised prison. These officers probably clung to a last hope that intruders dressed in sailor attire were not technically expert enough to carry off such a doomsday act.

A rigidly enforced protocol was imposed on Soviet missile submarine commanders, which was designed to prevent accidental or unauthorized launch of a nuclear missile. The Soviet General Staff in Moscow had to transmit orders to a submarine that a red-alert situation existed. A transmitted order to prepare for missile launch implied that a nuclear strike against the motherland was imminent or in progress, and the Soviet sailors were trained to obey without further question.

Under the protocol, only at that point would the submarine commander open a prepackaged set of orders directing the sub to a target. These sealed instructions would define the course to coordinates at an appropriate launch site located near the sub’s general patrol area.

Once the submarine had been positioned near the proper location for a launch, the captain and political officer normally waited for the confirmation order from fleet headquarters to launch the missiles. This final signal from headquarters included a set of codes to be added to the captain’s codes, thereby completing the information required to conduct the launch sequence.

Another package kept in the safe of the submarine commander would then be opened. This package contained the codes to be entered into the nuclear missile control and guidance systems. The combined codes would also unlock the missile’s fail-safe system.

The next critical step in the launch procedure required close coordination among the three ranking members of the submarine crew—the submarine commander, the deputy commander, and the

zampolit.

This step was to be taken only after each of these officers independently verified that the General Staff transmission was authentic and produced an individual key to the launch console.

On that night, this carefully designed procedure was not followed. But how could this have occurred when the stakes were so high? Had the first captain and second captain been overpowered, or were they obeying forged orders? Could lower-level regular officers assigned to the boat have been induced to participate in some mad scheme?