Red Star Rogue (15 page)

Authors: Kenneth Sewell

The Navy’s spy-scientists were already involved in a deep-sea intelligence project, code-named Sand Dollar, with the mission of finding and recovering Soviet technology that routinely crashed into the oceans during missile tests, shipwrecks, and plane crashes.

The search for K-129 thus began as a small operation assigned to a highly specialized group of submarine officers and civilians.

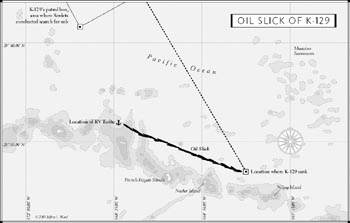

Before the investigation could get underway, another incident involving the lost submarine came close to exposing the secret operation to the public. Soon after the sinking, a University of Hawaii oceanographic research ship accidentally came upon an oil slick hundreds of miles south of the Soviet search site. This large pool of pollution was floating on the surface and drifting slowly away from any landmass as it dispersed.

The oceanographic research vessel the university operated in early 1968 was the R/V

Teritu,

a ninety-foot converted yacht, with a rounded bottom that restricted it to working close to land. The

Teritu

was not suited for deep oceanographic work, which required carrying a considerable amount of heavy equipment on the upper deck. A much older research ship at the university, the

Neptune,

was past its time for retirement from service, and in 1968 was probably used only for minor projects in the immediate vicinity of the main islands.

At the time the

Teritu

discovered the oil slick, it was conducting studies along the Hawaiian Leeward Islands. The university research ship was operating in an area north of Necker Island, Gardner Pinnacles, and French Frigate Shoals. The

Teritu,

because of its limited size, stayed fairly close to the long chain of low and submerged islands that runs from Oahu to Midway Island. The chain consists of more than a hundred volcanic islets, atolls, and coral reefs. The uninhabited islands, some less than two hundred acres in area, and others completely submerged beneath the ocean surface, contain one of the world’s richest ecosystems.

In the midst of a routine expedition in March, the research boat accidentally sailed into the large oil slick, probably in the vicinity of the Gardner Pinnacles. Quickly taking samples and testing them in the boat’s small chemical laboratory, the scientists on board were horrified to discover the oil slick was heavily radiated. Later analysis of the oil slick identified Chinese fissile material and light diesel oil. The oil was of a type used by submarines to lessen the amount of smoke exhausted during snorkeling. The diesel engines of Golf submarines used a high-grade, nearly smokeless fuel called D-37. Attack submarines burned a different grade fuel called solar oil.

The scientific crew aboard the research boat was so disturbed by the discovery of radioactive waste that it radioed its finding to the university’s research center before returning to Honolulu. The alarm was relayed to the head of the university’s oceanographic and geophysics department, Dr. George P. Woollard. Dr. Woollard, who was working with the U.S. Navy on securing a number of research grants, called his contacts at Pearl Harbor to determine if the military was aware of a radiation-laced oil spill in the Leeward Islands.

Before anyone could make the information public, “government representatives” (probably from the Office of Naval Intelligence) moved in. Mysteriously,

Teritu

’s deck logs for that period of time—the legal documents normally kept as a routine part of a ship’s history—were lost, deliberately misplaced, or seized by the DIA.

The records and eyewitness accounts had to be immediately embargoed, otherwise the exact location of the sinking of K-129 could have been quickly pinpointed by anyone reviewing the widely available charts of winds and currents in the vicinity at that time. If an announcement about the discovery and location of an oil slick had been made public, the Soviets could have easily linked it to their lost boat and determined the site of the sinking.

The general location of this oil slick, carried by ocean waters to a point near the Leeward Islands, proved that K-129 had gone down close to the islands and approximately three to four hundred miles northwest of Honolulu. Sea charts of this area for March 1968 revealed that the prevailing currents and winds would have carried the oil spill in a southwesterly direction almost parallel to the islands. Had K-129 sunk farther to the north, where the Soviets were centering their search, or where American intelligence falsely claimed the sub had sunk, the currents would have carried the oil spill into open ocean waters in a northerly direction.

It can also be determined that the

Teritu

crew discovered the oil spill soon after the submarine sank, because the light D-37 diesel fuel carried by K-129 would have been broken up by sea surface motion and evaporated in a few days. The heavy plutonium particles mixed in the oil would have then dropped to the seabed. Thus, the oil slick had not moved far from the wreck site when it was discovered.

This dangerous radioactive waste would have completely dissipated from the surface into the ocean before making landfall. There probably never was a great risk of contamination from the oil and fissile material, because the fishery in that area was inhabited by schools of pelagic fish that did not feed or spawn on the ocean floor. The long-term effects of radioactive contamination were not as well documented in 1968 as they are today. The University of Hawaii probably believed the contamination posed no health risk to the local human population or the ecology of this pristine wildlife area. Moreover, it is unlikely the oil slick could have been contained, even if its presence had been known by the public.

However, there is evidence that the U.S. government appreciated the university’s cooperation. Almost immediately after the incident, the university’s oceanographic programs began receiving Navy research grants and contracts it had long sought. Within two months of discovering the oil spill, the school had acquired the kind of research ship it had always wanted. A remodeled Admiral-class Navy minesweeper was outfitted as a research ship and rechristened the R/V

Mahi.

The 184-foot ship, twice the size of the university’s small research yacht, was leased from the Dillingham Corporation. Dillingham Corporation, with extensive facilities in the Hawaiian Islands, had performed work under numerous contracts for the Navy and other government agencies. Within three years, the university’s oceanographic research program was able to acquire, again through a charter with a private company, the modern 156-foot research vessel

Kana Keoki.

This deep-sea research ship was specially designed for ocean expeditionary work.

It was imperative that the

Teritu

’s discovery of the oil slick be kept secret for the DIA’s clandestine search and exploitation of the Soviet submarine. It was equally important that the location of the Soviet submarine’s wreckage remain hidden from the searching Soviet navy. The research vessel’s sampling of the radioactive oil slick, if publicized, would have jeopardized the secret recovery operations before they were launched.

This vital piece of intelligence proved that the K-129 sank far closer to Hawaii than the government was ever to reveal. The oil slick sample returned by the

Teritu

proved that the source of the radiation could only have been from a smashed Soviet ballistic missile warhead. Thus, the boat’s logs had to be suppressed, and its crew sworn to secrecy.

More than thirty years after the incident, spokespersons for the University of Hawaii claim they have no idea what happened to the ship’s deck logs. The

Teritu

’s crew and scientists who were aboard at the time refused to be interviewed about their discovery. The crew members of the research ship were compelled by federal agents to sign confidentiality agreements, never to discuss the voyage that discovered the radiated oil slick off the Hawaiian Islands.

I

N THE EARLY MONTHS OF

1968, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency was already reeling under crushing caseloads resulting from North Korea’s seizure of the USS

Pueblo

on January 23, and North Vietnam’s unexpected massive Tet Offensive launched at the end of February. The new K-129 assignment was added to its intelligence-gathering burden because the mysterious behavior and sinking of the Soviet missile submarine near Pearl Harbor set off alarm bells in Washington.

The Pentagon wanted to know why a Soviet submarine went missing so close to America’s strongest Pacific asset, and the DIA was tasked with providing answers without delay. With its operatives and analysts already overextended, the agency reached into the U.S. Navy’s pool of scientific talent to draft a small team of deep-sea experts for the job. The man named to head the team was one of the Navy’s best and most experienced civilian underseas experts, Dr. John Piña Craven.

The Navy had recently established a special unit known as the Deep Submergence Systems Project (DSSP). The unit’s mission was to develop underseas surveillance equipment and systems for the exploration and exploitation of the deepest parts of the sea. Dr. Craven, an oceanographer and engineer who had served as chief scientist on the highly successful Polaris submarine missile program, was the unit’s director.

The expertise of the DSSP members selected for the K-129 project was tailor-made for the challenge at hand. Dr. Craven was immediately called to Washington for a consultation. The project would be coordinated by Admiral Philip A. Beshany, one of the Navy’s top submarine sailors.

The team’s first task was to find the wrecked K-129 without the Russians or anyone else knowing that the U.S. Navy was even looking for it. When a quick review of the scanty information about the submarine revealed its peculiar behavior before sinking, U.S. naval intelligence had reason to be concerned about its mission. The ballistic missile submarine had been operating far too close to vital American defense facilities. This latest incident was too similar to some aspects of the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor to be ignored.

The fact that the Soviet search-and-rescue ships were in the wrong place—coming no closer than four hundred miles from the general vicinity where the U.S. Navy believed the submarine had sunk—only added to the Americans’ worries. In the atomic age, a navy with nuclear warships was supposed to know exactly where its submarines were operating at all times. The very idea that a nuclear-armed submarine was lost was cause enough for an urgent response.

As the Soviets’ futile search stretched into weeks, the admirals of two great navies grew increasingly worried, but apparently did not notify each other or ask for assistance. The Soviets in Vladivostok and Moscow were heartsick at the prospect that one of their submarines might have carried nearly one hundred sailors and officers to their deaths. Beleaguered American admirals feared the worst about the odd behavior of an enemy missile carrier in their own backyard.

But the American and Soviet admirals’ unease and frustration over the fate of K-129 were no doubt dwarfed in comparison to the rising fears of a small group of men in the Kremlin with no obvious connection to naval matters. The lost submarine had not done what it was expected to do, and a monstrous scheme with potentially earth-shattering ramifications had begun to unravel on the day K-129 was reported missing.

Another incident, which at first seemed unrelated to the K-129 loss, further complicated the developing life-and-death drama unfolding in the North Pacific. A Japanese spy, operating undercover near a U.S. Navy facility on Honshu Island, observed a damaged American submarine put into port on March 17. The American attack submarine USS

Swordfish

sailed into the huge U.S. Navy base at Yokosuka, needing repairs. The submarine was apparently not attempting to hide the damage to its conning tower, since it entered the navy yards at the mouth of Tokyo Bay, on the surface, in broad daylight.

At first, the spy’s report to his KGB handlers in the Soviet embassy in Tokyo was passed off as another piece of routine intel. The Soviets received reams of daily reports from spies working the scores of American bases and camps in the Japanese Islands. Japan’s openly democratic society provided a plethora of intelligence opportunities for the Soviets during the years of the Cold War. A large Communist Party organization flourished in Japan, fueled by growing anger with the American occupation since the end of World War II. While it was no longer billed as an occupation, America maintained a huge army, navy, and air force presence throughout the island nation.

What finally grabbed the attention of the Soviet intelligence agents about the

Swordfish

report was the timing: The American submarine had entered port only a few days after K-129 went missing. Soviet naval intelligence quickly seized on this tidbit to make the erroneous assumption that the Americans were complicit in the loss of their submarine. This fallacious interpretation of human intelligence became one of the enduring myths of the K-129 incident and may have led to a horrific act by the Soviet navy—the revenge sinking of an American submarine two months later, in another part of the world.

Retired admiral Ivan Amelko, commander of the Soviet Pacific Fleet in the late 1960s and early 1970s, was the first high-ranking Soviet naval officer to make the charge that the U.S. Navy had caused the sinking of K-129 and the deaths of ninety-eight Soviet seamen. He claimed an American submarine had crashed into the Soviet sub while shadowing it in the North Pacific. He said he had learned that the American attack submarine

Swordfish

had made “entry to the Japanese naval base at Yokosuka for cosmetic repairs” from a local Japanese newspaper. This was obviously a clumsy attempt to hide the fact that Japanese spies were active in the area.

The widely held theory that K-129 was sunk by an American submarine became gospel for Soviet mariners, who still cling to this story today. Another former Soviet officer, Admiral Viktor A. Dygalo, claimed to have seen wreckage photographs showing an opening in the bottom of the doomed Soviet boat that could only have been caused by the

Swordfish

’s conning tower ramming and punching a hole in its hull.

In reality, the ramming of K-129 by the American submarine as the cause of the sinking is not only implausible, but technically impossible.

Had the conning tower of a submerged submarine come in forceful contact with the hull of a Soviet Golf-type submarine, both boats would have suffered severe damage. When 12.5 million pounds of steel—the approximate combined weight of the two submerged submarines—crashed together in the high-pressure environment of the sea, the damage would have been catastrophic to both boats.

The Golf’s hull along the central section of the boat was heavily reinforced with a huge steel keel to support the weak section created by extending the design of the German U-boat to accommodate the missile tubes. The reinforced bottom of the K-129 was its strongest area.

On the other hand, the conning tower on the USS

Swordfish

was the weakest and most vulnerable part of that submarine. It was not designed to take the force of an impact. Such a collision would have caused far more damage to the

Swordfish

than was reported by the Japanese spy.

A second fact refutes the Soviet theory about the involvement of the American boat in the K-129 disaster. The USS

Swordfish,

which was based at Pearl Harbor, would certainly not have sailed thousands of miles from the site of the K-129 to Yokosuka, Japan, for emergency repairs, when its home port was less than four hundred miles away.

The

Swordfish,

commanded by Captain John T. Rigsbee, had slight damage to its periscope housing and upper conning tower. Captain Rigsbee had the repairs done at Yokosuka so he could quickly return to his mission. The U.S. Navy will not reveal exactly what that mission was, but it is reasonable to surmise it had something to do with surveillance of Communist activities surrounding the recently pirated intelligence ship, USS

Pueblo.

The Americans had assigned every available asset to determine what the North Koreans were doing with the captured ship.

The

Swordfish

was regularly assigned to monitor Soviet and North Korean naval activity in the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk north of Japan. The Americans claimed the damage to the submarine resulted when it struck a small iceberg during one of its routine patrols.

“While on patrol on March 2, 1968, the USS

Swordfish

collided with pack ice,” an American diplomat informed the Russian government in an official communiqué, years later. “She returned to Yokosuka on March 16 and subsequently entered dry-dock for repairs. However, on the eleventh [sic] of March when the Golf class submarine sank, the

Swordfish

was over 2,000 miles away from the Golf’s position.”

At the time there was ample reason—beyond merely looking for someone else to blame—for the Soviet admiralty to suspect U.S. Navy involvement in the disappearance of its boat. By the late 1960s, American and Soviet submarines routinely challenged one another for dominance of the deep in deadly games of hide-and-seek. Frequently the games turned more aggressive and became tag matches.

“There have been numerous near collisions involving ships of the U.S. Navy and the Soviet fleet,” complained a CIA intelligence report, dated January 27, 1968. “The harassment tends to be more severe when U.S. ships are operating in areas the Soviets feel are ‘their’ waters, such as the Sea of Japan.”

In a few cases, the games turned even more dangerous, when boats deliberately came too close and roughly collided. The American equipment was stealthier and the American crews more cocky. Their tactics enraged the Soviet submarine officers. At one point in the Cold War, the Soviet navy commander in chief, Admiral Sergey Georgievich Gorshkov, became so irate at a U.S. sub tailing one of his submarines that he reprimanded his boat’s skipper for not ramming the brazen American. The incident took place in the Barents Sea between the K-19 and the USS

Nautilus.

The American boat was caught in a vulnerable position. It would have sunk if the captain of the K-19 had rammed it, while the Soviet boat would have only been damaged.

Admiral Gorshkov was a strong proponent of the underseas competition between American and Soviet submarine crews. The dangerous contests were not all games. These aggressive maneuvers were considered valuable practice for real underseas warfare when and if the Cold War turned hot. The admiral would not have hesitated to demand an eye for an eye if he believed that one of his submarines had actually been sunk by an American in the course of playing this deadly game.

A hard-line survivor of Stalin’s purges of the military, Gorshkov was nevertheless a pragmatic naval disciplinarian, not a political fanatic. He would not have tolerated a submarine commander in his elite corps who dared make a decision to launch a sneak attack on an American city without authorization. Though the gruff-speaking admiral would have ordered a total launch against scores of American targets at once, he would never have conspired in or countenanced a rogue attack without specific and verifiable orders from his superiors in the Kremlin.

Gorshkov was in charge of General Secretary Brezhnev’s massive naval buildup, particularly the rapid expansion and upgrading of the submarine force. Under the admiral’s leadership, the Soviet navy built the largest submarine force in the world, with nearly five hundred underseas craft of all types.

Neither the Americans nor the Russians had forgotten the troubled months following the Cuban Missile Crisis. It had been fewer than six years since that near-nuclear confrontation. Many Soviet naval leaders believed their politicians had blinked and brought shame on the Red Fleet. Ballistic missile submarines, including Golf-type submarines, had been ordered to Cuba. But the crisis was resolved by Khrushchev’s withdrawal of nuclear missiles from the Cuban island before the Soviet boats could leave their bases. Only attack submarines reached Cuban waters, and these crews were forced to the surface by constant American antisubmarine warfare harassment.

The Americans had won every encounter in the seas surrounding Cuba, and the Soviet submarine force—which consisted entirely of attack submarines—had tucked tail and run for home. Admiral Gorshkov never forgot or forgave the American Navy for this humiliation, and like many military leaders in the Soviet Union, he was particularly angry with Khrushchev for caving under American naval threats.

This lingering hostility toward the U.S. Navy in the top ranks of the Soviet admiralty was further inflamed by the loss of K-129. The growing animus could well have led to another maritime tragedy involving an American sub in the Atlantic, a few weeks after the K-129 disappeared.

Dr. Craven’s team had barely begun the hunt for K-129, when they were ordered to shift attention from the Hawaiian waters to a more urgent priority—finding another submarine that had gone down without a trace. This time it was an American attack submarine, and the site of the disappearance was an ocean away.

The USS

Scorpion

had been sailing from a lengthy deployment in the Mediterranean to its home port at Norfolk when it was diverted to investigate a strange assembly of Soviet warships near the Azores in the eastern Atlantic. The

Scorpion

disappeared on May 24, 1968, while returning from that clandestine mission. Speculation was rampant among submariners in both the United States and the Soviet Union that the

Scorpion

had been sunk by a Soviet torpedo.