Reporting Under Fire (13 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

This was the worst poverty Martha had ever witnessed, and she was horrified. Everywhere she went in China, she encountered the same. Martha couldn't forget the pavement sleepers in cities, bent-over peasants in the countryside, lepers with missing noses, people hawking and spitting everywhere, and everyone stinking of sweat and “night soil.”

She and Ernest made their trips into free China escorted by a translator, Mr. Ma, who had a bright smile and a dim command of English. They rode by car and truck, up and down rivers by motorboat and sampan, overland by uncommonly small horses, and sometimes on foot. It poured rain in that cold spring of 1941, and Martha's writings spoke of mud, fleas, bedbugs, sewage, Mr. Ma's smiling but useless interpretations, and Ernest's miniature horse that slipped, only to have Ernest pick it up and carry it. Martha was miserable, and several times her new husband reminded her that coming to China was her idea.

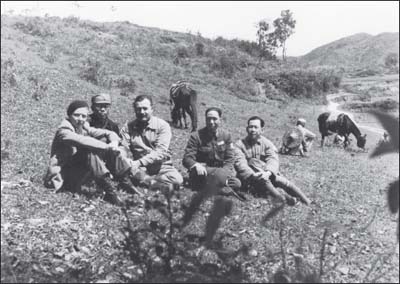

Martha Gellhorn posed with her then-husband Ernest Hemingway as she wrote about the Sino-Japanese war for

Collier's

magazine.

Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

They never saw any fightingâthe Nationalist Chinese army operated as a defensive force but didn't directly attack the Japanese occupiers. Yet they admired the Chinese soldiers they met, who earned even less than the pitiful coolies, and marveled at their endurance. Soldiers often went barefoot and lived for years isolated in the countryside far from home. There was no mail service to bring news of their families, a point that did not matter, Martha related wryly, because the soldiers couldn't read. Ernest stood in the rain to make rousing speeches to the forgotten men, whom he admired for their toughness and skill. Ernest, who had watched them stage a mock assault, had an eye for that kind of thing and knew these troops were well trained.

Ernest flattered the generals they met and engaged them in long sessions of drinking each other under the table, a show of hospitality among the Nationalist officers. Martha noticed that the generals lived in relative comfort in cities far from the camps in far-flung places where their soldiers lived and trained.

Martha and Ernest traveled into Chungking, free China's capital, courtesy of the Nationalists. They were caught off guard when a Dutch woman asked if they'd like to meet Chou En-lai, a name that meant nothing to Martha. She and Ernest gave their government escort the slip and were taken, at times blindfolded, to the man who was second-in-command to Communist leader Mao Tse-tung (Mao Zedong). Educated in France and equipped with an urbane air, Chou, though he used a translator, obviously understood the conversation. Martha liked him immediately. She felt at home with him, the first and only time she had that rapport with someone in China. But she couldn't write about Chou in an American magazine like

Collier's

âChina's politics were far too touchy, and Martha felt constrained

by the fact that she and Ernest were guests of the Nationalist government.

Quite the opposite was her introduction to Nationalist China's power couple, Chiang Kai-shek and his elegant wife Soong May-ling. Chiang had married well: Madame Chiang's father was Charlie Soong, a rich and powerful businessman who had an American education. Madame Chiang, educated at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, spoke excellent English and behaved like a co-ruler. Madame shared Chiang's utter hatred of both the Japanese, who had invaded her country, and the Chinese Communists, who threatened the Nationalists from inside. The couple kept close diplomatic ties to Washington, and most Americans viewed them as the saviors of democracy in China against the Communists.

Madame Chiang and Ernest were having a pleasant chat when Martha interrupted. Why, she asked, did China force its lepers to beg in the streets? Madame Chiang went ballistic. She retorted that the Chinese “were humane and civilized, unlike Westerners; they would never lock lepers away out of contact with other mortals.” She lectured Martha with words that bit: “China had a great culture when your ancestors were living in trees and painting themselves blue.”

Clearly, Chiang and his wife had no concern for the well-being of China's millions of people. This was no democracy; any notion of a free China was a joke. Again Martha felt that she couldn't share her opinions publicly. It would be bad manners, not to mention grossly undiplomatic, to criticize Chiang and his wife in print. It was a tough lesson for Martha Gellhorn, who felt she had compromised her integrity as a journalist.

In the end, Martha's journey to China, for which she'd had such high hopes, left her exhausted and deflated. Ernest had far more fun, and he criticized her gloom. “He saw the Chinese as

people, while I saw them as a mass of downtrodden, valiant, doomed humanity. Long ago ⦠U.C. declared as dogma âM. loves humanity but can't stand people,'” said Martha later, quoting Ernest. “The truth was that in China I could hardly stand anything.”

They took up married life in Ernest's villa in Cuba, but when the United States entered World War II that December, Martha left for Europe. Her long absencesâthis one for monthsâirked her husband, but she was not content to be simply Mrs. Ernest Hemingway. She urged Ernest to join her in England and proposed that he write for

Collier's.

Ernest stayed in Cuba as Martha kept writing.

Collier's

paid well, and she generated 26 articles between 1938 and early 1944. Ernest's mood worsened, and their marriage began to crack. When Martha finally returned home, their relationship turned into all-out war. Ernest changed his mind about going back to journalism and secured credentials as a war correspondentâfor

Collier's.

As a big-name author, Ernest overshadowed Martha's credentials. He would be higher paid, and worse, Ernest was now the

Collier's

reporter with a guaranteed seat on a seaplane to Europe. D-Day was coming, and both Ernest and Martha planned to cover the coming Allied assault on the beaches of France. Ernest had official credentials, and Martha didn't. Ernest Hemingway had upstaged Martha at

Collier's,

when any magazine would have welcomed him to write its cover story.

While Ernest few comfortably in an airplane, Martha made her way to Europe on a Norwegian freighter loaded with amphibious assault boats and dynamite. When she arrived at London's Dorchester Hotel, she found Ernest spending time with a lively blond reporter named Mary Welsh, who worked at the London bureau for

Time, Life,

and

Fortune

magazines.

When word reached London that D-Day had begun, Martha wandered the docks looking for some way to get across the English Channel to Normandy. She managed to stow away on a hospital ship, hoping to be taken for a nurse if anyone spotted her. Martha went ashore at Omaha Beach and trailed stretcher bearers recovering wounded soldiers, Americans and Germans alike. She was discovered when she went back to England, and the military banished her to a training camp for American nurses. Still, she got some satisfaction knowing that Ernest had to settle for observing D-Day from a landing craft; his feet never touched the ground in France. Their invasion stories ran in

Collier's

that summer; critics would observe later that Martha wrote the better piece. She worked steadily for

Collier's

throughout the war; Ernest also did war reporting and courted Mary Welsh.

Martha and Ernest divorced in 1946. For the rest of her life, Martha Gellhorn had little good to say about Ernest Hemingway.

After the war, maternal instincts stirred, and Martha went to Italy to adopt a little boy whom she nicknamed Sandy. The slim, chain-smoking Martha kept her weight at 125 pounds no matter what, and Sandy was a pudgy child. Martha equated obesity with laziness and never forgave Sandy for being fat. He proved to be a huge disappointment to her, and in her blunt style, she told him so. When she married again in 1963 to a

Time

editor named Tom Matthews (they divorced nine years later), she got on far better with her stepson, also named Sandy.

Martha Gellhorn became the 20th century's most famous woman war correspondent. Her best-recognized piece arose out of her visit to the Nazi death camp at Dachau in April 1945. A few days behind Marguerite Higgins and Margaret Bourke-White, Martha arrived as railroad cars had been cleared and their dead human cargo buried. But the horror lingered. “Behind the

barbed wire and the electric fence,” she wrote for

Collier's,

“the skeletons sat in the sun and searched themselves for lice. They have no age and no faces; they all look alike and like nothing you will ever see if you are lucky.” Ernest Hemingway could not have penned words any more devastating.

Martha went on to report from war zones around the world, each year more convinced that warring governments were evil. She yearned to report from Vietnam but had to wait until a British newspaper, the liberal

Guardian,

gave her credentials and a plane ticket to Saigon. Martha took things personallyâshe felt responsible for every “wounded, napalmed, amputated Vietnamese child” because the United States backed South Vietnam. Famously, she was said to scorn “all this objectivity shit” in her reporting. Sickened by what she saw as the loss of innocent life, she wrote articles so scathing that the South Vietnamese refused to renew her visa. No doubt the US government approved.

Gellhorn also held strong, pro-Israeli views about the Middle East and favored Israel in its ongoing conflict with Arab states. If Martha Gellhorn saw something that she believed was unjust, then it was decidedly wrong. She refused to look at both sides of an issue she felt passionate about. As a child, Martha had been raised on the principles of ethical culture and was an atheist, but she had two Jewish grandfathers and, after witnessing the inhumanity of Nazi death camps, an abiding love for Israel.

She equally despised Yasser Arafat, the self-appointed leader of Israel's Palestinian Arabs. Martha was quite blunt in her criticism of the Middle East's “oil Arabs” who ganged up on Israel, and the only Palestinians she liked were women. “The Muslim Arab attitude toward women is one of the reasons that Arabs remain so drearily retarded,” she wrote in

The View from the Ground,

a look back at her career as a correspondent. “The chief reason is hate. These people really love to hate.”

Martha Gellhorn relished life, and some would say she ran from death. She didn't accept old age with grace. She had a home in London, but as she aged, she withdrew to spend more and more time at her cottage in Wales. She surrounded herself with younger people; her favorites were young men whom she called her “chaps.” She smoked unceasingly, her sand-edged voice marked by the transatlantic accent adopted by Americans who lived in Europe.

Martha Gellhorn was hell-bent on staying relevant and deeply saddened when she felt too old to cover the war in Bosnia in the early 1990s. Late in life her body betrayed her, and she developed cancer in her nose. When she started to go blind, she decided she'd had enough. In February 1998, she dressed in a yellow nightgown and climbed into her bed, made up with yellow sheets. With headphones over her ears and an audio book in her cassette player, she overdosed on sleeping pills. She was just shy of 90.

A new generation of Americans was introduced to Martha Gellhorn in a made-for-TV movie that portrayed her marriage with Ernest Hemingway. She would have hated it, although she might have grudgingly admitted that Hemingway helped her through a period of writer's block during the Spanish Civil War.

Shortly after she died, Sandy Matthews, Martha Gellhorn's stepson, gave an interview to the

Guardian

to dispute a new biography that portrayed Gellhorn with “sexual scandal-mongering and cod psychology.” He'd had an affectionate relationship with her over the years, and Martha had asked him to settle her estate after she died. John Pilger, one of her “chaps” in her later years, also defended her memory, recounting how Martha, at age 75, got into her car and drove into the Welsh hills to cover a miner's strike that bitterly divided Britons.

Most of the media were then concentrating on miners' violence on the picket line, which echoed [British prime minister Margaret] Thatcher's “enemy within.” She phoned me from a call box in Newbridge. “Listen,” she said, “you ought to see what the police are doing here. They're surrounding villages at night and beating the hell out of people. Why isn't that being reported?” I suggested she report it. “I've done it,” she replied.

The German Army invaded Poland on August 31, 1939, immediately drawing most of Europe into World War II. American reporters stayed at their posts in Berlin until the United States entered the war in December 1941.

The United States fought the war in two theaters in Europe and the Pacific. American women reporters found their way to both. Experienced correspondents such as Virginia Cowles (who wrote for the London

Sunday Times)

and Martha Gellhorn, both of whom had witnessed the Spanish Civil War, turned their attention to Germany's invasion of Poland and Czechoslovakia. Sonia Tomara, a Russian exile, and Tania Long, a naturalized American of Russian-English descent, were hired by the

New York Herald Tribune.