Reporting Under Fire (14 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

Helen Kirkpatrick fought her own battle to win a spot reporting from London for the

Chicago Daily News.

In September 1940 she and her friend Ginny Cowles observed the Royal Air Force from the White Cliffs of Dover as Spitfires and Mustangs fought the Battle of Britain. They both endured the Blitz in London

when the German

Luftwaffe

dropped bombs night after night on Britain's cities.

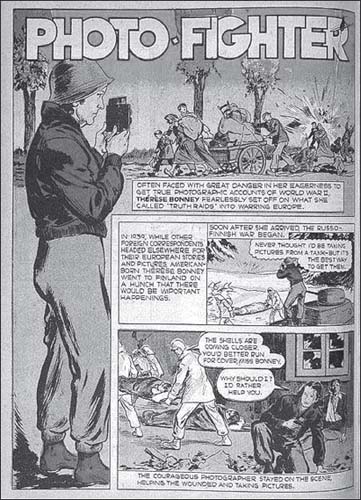

Photographer Therese Bonney became a comic book hero during World War II.

Library of Congress LC-USZC4-9007

There were others in Europe: Ruth Cowan, Eleanor Packard, May Craig, Ann Stringer, Patricia Lochridge, Marjorie Avery,

Catherine Coyne, and Betty Murphy Phillips, the nation's first African American war correspondent, who had the bad luck to get sick before she had a chance to get to the front. Four had cameras: Toni Frissell, a high-fashion photographer for

Vogue

and

Harper's Bazaar;

the flamboyant Lee Miller, also of

Vogue

; Therese Bonney, who focused on the plight of children and adults left homeless by war; and

Life

magazine's Margaret Bourke-White.

Later, American women gained credentials from the US Navy to cover the fight against Japan. As the Battle of Iwo Jima unfolded in the Pacific in 1945, Patricia Lochridge and photographer Dickey Chapelle worked aboard hospital ships. Old-timer Peggy Hull reported from a land-based hospital on the island of Saipan.

REPORTING FROM MOSCOW, TUNIS, AND BUCHENWALD

We climbed over the rail and into lifeboat No. 12. Even though we knew the torpedo splash was there, it was a shock to find ourselves sitting in water up to our waists. As we started slowly downward, I hugged my musette bag to my chest, hoping to keep my camera dry.â Margaret Bourke-White

“Wait,” Father said, and then in a rush the blackness was broken by a sudden magic of flowing metal and flying sparks. I can hardly describe my joy. To me at that age, a foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty.

Pure joy. That visit to the foundry to watch the first steps in building a printing press was a treasured memory for Margaret White. She cherished those few hours when her father, a brilliant but distant man, came out of his usual trance and paid attention to her. Joseph White was an inventor who happily spent most of his waking hours pondering the best way to design printing presses and glorious color images.

While Father “thought,” Margaret's mother, Minnie Bourke White, busied herself with her three children, partly to keep them from distracting Father and partly because Minnie White raised her children to be fearless. Together they explored the wide outdoors, and Margaret returned home with masses of pollywog eggs and leaves to feed the hundreds of caterpillars that lived on a dining room windowsill. A budding herpetologist, she kept a menagerie of pet turtles and snakes, including a baby boa constrictor that lived in a blanket and a “plump and harmless puff adder.” (Margaret never explained why that puff adder, a deadly, venomous snake, was “harmless.”)

When Joseph White broke away from mulling over his latest patents, the family took outings and vacations. When Margaret was a little girl in the early 1900s, amateur photography was a novelty among American consumers. Always the inventor, Joseph White played around with camera lenses and 3-D images; he was fascinated with how light played through lenses, prisms, cameras, and projectors. For those who could not see at all, Joe White invented the first Braille printing press.

Margaret didn't think she fit in with the other girls at Plain-field High School in New Jersey. Inner-directed, she had a strict conscience and far more self-control than others her age. Her mother had taught her never to take the easy way out of anything and to always tell the truth, and Margaret didn't question

being punished even for childish carelessness. Margaret and her sister had to be content with wearing cotton stockings when the other girls wore silk, and colorful Sunday funnies were yanked from newspapers before they read them.

Margaret adored dancing, and though she had plenty of boys around for picnics, canoe trips, and steak roasts, she never was asked to dance at school parties. When she took the top literary prize her sophomore year, she still stood neglected at the dance that followed, a dejected and dismal wallflower until an older girl volunteered to dance with her. Margaret was sure the older girl felt the same way she did, “that we both could be stricken invisible.”

Margaret enrolled to study art at Columbia University in New York City. Though she was unaware of it then, it was a stroke of luck when she signed up for a weekly two-hour photography class with Clarence H. White (no relation), whose innovative images were the talk of the avant-garde. Professor White and his crowd of protégés strove to elevate photography as an art form at a time when critics relegated “art” to painters, sculptors, and architects.

Margaret wasn't especially interested in taking pictures, but White's class offered her a chance to explore design and composition in a new medium. What was more, she took the class while nursing a broken heart; her beloved father had died during Christmas break. Sometime thereafter, Margaret's mother bought her a camera, a 3¼-by-4¼-inch Ica Reflex, modeled after the much pricier Graflex camera. At $20, the Ica still was a costly purchase for her mother, and Margaret's new camera came with a cracked lens.

Margaret set her camera aside as she pursued new paths in her education. She moved on to Rutgers University for the summer session and then to the University of Michigan for the fall

term. There she met a tall, attractive graduate student named Everett Chapman. “Chappie” saw Margaret as they passed through a revolving door and wouldn't stop circling until she said yes to a date.

Margaret the wallflower had begun to bloom. It was love at first sight for her and Chappie, and they married quickly. Chappie planned to teach at Purdue University as Margaret resumed her studies, now in herpetology.

Their marriage was short-lived, thanks to an unbroken “silver-cord entanglement” that held Chappie to his mother. The elder Mrs. Chapman had wept all through his marriage ceremony to Margaret. Chappie departed for Ann Arbor, Michigan, and left them both at the family cabin. Mrs. Chapman took advantage of his absence to tell Margaretâthrough a wallâ “You got him away from me. I congratulate you. I never want to see you again.”

Margaret left and walked the 17 miles to Ann Arbor to find Chappie, thinking that would make things right. However, though they loved each other, neither Chappie nor Margaret had the life experience to deal with his dominating mother. Their marriage lasted two years, until Margaret left Chappie and went back to school.

By now Margaret had attended six different colleges, and her interests ran wide. She had studied art, herpetology, and paleontology. For her senior year she picked Cornell University in upstate New York, attracted to its lovely photos of waterfalls and Cayuga Lake. Just about penniless, she enrolled in the fall of 1926 to study biology, planning to get a job to help pay her expenses. But jobs were gone by the time Margaret arrived in Ithaca, so she picked up her camera. With such scenery all around, she thought, surely she could sell her photographs, and for a time she did, as holiday gifts.

Margaret got her marketing lesson when sales dried up in January and she was left with piles of her photos on her dorm room floor. She found a different customer, this time Cornell's

Alumni Review,

where her shots appeared on the cover. When Cornell alumni advised Margaret to become an architectural photographer, they “opened a dazzling new vista,” and she made herself a plan.

Margaret graduated and took the Great Lakes night boat from Buffalo, New York, to Cleveland, Ohio, her legal residence. She went to the courthouse, got her divorce, and took back her maiden name, adding a hyphen between “Bourke” and “White.”

Margaret started her photography business in the Flats of Cleveland, a gritty industrial area along the Cuyahoga River. She didn't mind the dirt and stench of mills and was captivated by “smokestacks on the upper rim of the Flats rais[ing] their smoking arms over the blast furnaces, where ore meets coke and becomes steel.” She longed to get inside to photograph the fires and sparks and giant cauldrons of molten metal. But steel mills were no place for a woman, she was told, and it took weeks before she was permitted to enter one. First she had to prove herself.

Margaret befriended a kindly camera shop owner, Alfred Hall Bemis, who became her mentor. He helped her build a developing lab in her apartment, shared all kinds of technical advice, and taught her that it was easy to make a “million technicians but not photographers.” When competition showed up, “Beme” counseled Margaret, “Don't worry about what the other fellow is doing. Shoot off your own guns.”

With hard work, talent, and the “luck” that came after endless rounds of picture taking and networking, Margaret finally got into the Cleveland mills. She faced long weeks of technical problems, because the mills' cavelike interiors, lit only by the glowing blast furnaces, played all sorts of light tricks on the

camera lens. Margaret experimented this way and that until she got the shots she was looking for. Her girlhood fascination with flowing metal and flying sparks blazed in her photographs of stark, raw beauty.

In the next two decades, Margaret Bourke-White earned her reputation as one of the nation's most skilled photographers. In 1929, she was hired to take photos for a brand-new project,

Fortune

magazine, the weekly brainchild of a young New York publisher named Henry Luce, who had launched

Time

magazine four years earlier.

Fortune

lived true to its name, highlighting the news of American business and industry where “pictures and words should be conscious partners.” Luce had spotted Margaret's compelling photographs of the Cleveland mills, and he expected her to bring the same eye for detail to her work at

Fortune.

Margaret's spare, black-and-white photographs captured American industry in a novel way. She saw industrial products as objects of beauty. Giant pieces of machinery, electrical lines, tiny watch parts, a row of perfectly positioned plow bladesâall of these were worthy subjects for Margaret's cameras.

Architectural photography continued to intrigue her. As the wind blew through Manhattan's streets in the winter of 1929â30, she photographed the rise of New York's Chrysler Building, a steel-shelled ode to Art Nouveau beauty. Margaret herself was portrayed in a famous photo when she crawled out her studio window onto one of the building's steel gargoyles, 800 feet above the ground, to take a picture.

Though the United States was deep into the Great Depression, Luce launched yet another magazine in 1936, this one called

Life,

a large-size weekly that featured more pictures than words. Margaret shot its first cover photo, of the massive concrete Fort Peck Dam, which appeared on November 23, 1936. The shot reminded readers of an imposing Egyptian temple, but

this was an American achievement, revered as a marvel of Yankee engineering.

But the despair of the Depression now overwhelmed Americans as no national crisis ever had. On assignment for

Fortune

in 1934, Margaret flew to Omaha, Nebraska, to photograph the Dust Bowl, dried-up farmland than ran from North Dakota all the way south to the Texas panhandle. Her pilot ferried her in a beat-up, two-seat Curtiss Robin, and they crash-landed on Margaret's final day of shooting. She took the crash in stride when she thought back to the bleakness she'd seen from the air. The land was a “ghostly patchwork of half-buried corn, and ⦠rivers of sand.” Its human occupants tore at her heart: “They had no defense and no plan. They were numbed like their own dumb animals, and many of these animals were choking, dying in drifting soil.”

Something new rose up in Margaret's soul. She began to think of people as subjects for her camera. “Here in the Dakotas with these farmers, I saw everything in a new light. How could I tell it all in pictures? Here were faces engraved with the very paralysis of despair.”

In the midst of a very successful career taking pictures for advertising agencies and doing magazine work, Margaret took a different path. She agreed to collaborate on a book with an author named Erskine Caldwell, who had made the headlines with his book,

Tobacco Road,

about southern sharecroppers who led lives of desperation and depravity. Caldwell wanted to prove that

Tobacco Road

was a realistic portrayal of sharecropping, and he needed photographs to help him do that.

Not sure at first whether they liked each other, Margaret and Erskine took off on a road trip through the Deep South and, somewhere along the line, fell in love. Erskine Caldwell, Georgia-bred, taught Margaret about his southern ways. Margaret

grew both personally and professionally as she realized that a photographer must put “more heart and mind into his preparation that will ever show in any photograph.” Her portraits of weathered, beaten women and men in

You Have Seen Their Faces

reflected her maturity as an artist when it was published in 1937. She and Erskine Caldwell married two years later.