Reporting Under Fire (19 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

Gloria fell for John “Demi” Gates, a military officer who worked for the Defense Department in a far-off country called Vietnam, a skinny band of land on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. Demi's Harvard background and suave demeanor enchanted Gloria, and when he left for the Vietnamese capital of Saigon in 1956, she chased after him. She arrived at Demi's hotel halfway around the world unannounced. He didn't send her home.

Gloria understood that Demi's status as an American military man masked his real job as an intelligence officer. Demi worked for the CIA, one of a pack of “Rover Boys” who quietly circulated through South Vietnam advising its army and carrying out select attacks against Communist interests. Demi had excellent connections, and he found Gloria a job writing public

relations pieces for a Filipino relief organization that had quiet links to the CIA.

Early on, Gloria discovered that the best stories came from people doing their jobs. She rode in trucks with Filipino doctors and nurses to care for refugees fleeing the north and Vietnamese peasants who lived in hamlets strung along the Mekong Delta. She sold one piece about the Filipinos to

Reader's Digest

and another to

Mademoiselle

that talked about the brilliant, posh young Americans who lived in Saigon, striving to make South Vietnam a shining example of democracy in Southeast Asia.

Demi returned to the United States in October 1956, ready to leave the CIA and make a fortune in the business world. At that point he and Gloria parted company, because Gloria was far too flamboyant to make a good corporate wife. Besides, she had other plans. Her dry, clever take on fashion and the world at hand had made her friends among other New York fashion writers, and in 1957, her friend Nan Robertson helped find her a job at the

New York Times.

She was also briefly married during this time, though it ended in divorce within a year.

This was the top, what she'd been hoping for, though once again, Gloria was slotted in the women's section in a remote office far from the male staffers who ran the newsroom. In 1957, that's what a girl didâuntil policy loosened up and some of her coworkers went on to bigger jobs at the

Times,

one as fashion editor, another to the foreign desk and as business editor. (Nan Robertson wrote a book about these newspaperwomen after they sued the

Times

for sex discrimination in 1974 and won, when the case was settled out of court.)

Gloria left her job in 1960 and moved to Belgium where she was married for a year, but like a first marriage in New York, this one also failed. She returned to the

Times

and worked out of its Paris and London offices. Somehow she finagled hard news

assignments, especially when the Vietnamese were involved. Through it all she still had the fashion beat; her final

Times

story before she left Europe was the “Lowdown from Paris” about the spring collections of Chanel, Givenchy, and Yves Saint Laurent.

She always campaigned to get to Vietnam, but men who ran the

New York Times

took a dim view of assigning women to cover the war. The prestigious newspaper already had a stable of male war correspondents to call upon. One, an upstart named David Halberstam, had won the Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his Vietnam reporting.

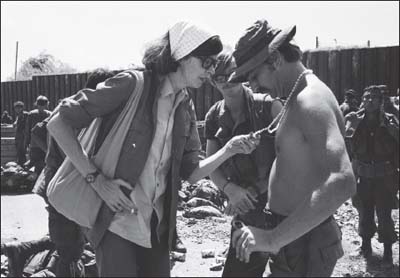

Gloria Emerson wrote about ordinary US soldiers during the Vietnam War.

Nancy Moran

Then the bosses changed their minds and sent Gloria to Vietnam, “allowed to go,” she believed, “because the war was supposed to be over so it didn't matter if a female was sent.” In March 1970, when she stepped off the plane and rode to her hotel, she was appalled. Gone was the lovely city that she

remembered from her days as a reporter in 1956, when Saigon's streets were lined with trees and its buildings and shops still bore the mark of French culture. Now Saigon was overrun with American soldiers. Its bar and brothel business thrived, sure of steady business from the Americans who were fighting against the Communist North.

In the coming weeks, Gloria filed stories that ranged wide and ran deepâhow war disrupted South Vietnam's middle class, and how the American officials destroyed black market marijuana because soldiers could buy it cheaplyâtwo bucks for a 10-joint pack. She was impressed by Vietnam's 1,000-year history of fighting for independence from any and all outsidersâ from China, from France, and now from the United States.

By now Gloria was 40 years old, and her instincts, opinions, and writing were sharper than ever. She caught the small details of war in the field and life in Saigon that other

Times

reporters had missed. Soon after arriving, she spotted a rack of postcards in a Saigon shop that sported scenes from the war that GIs liked to mail home. The bizarre notion of picture postcards with war photos was something that others hadn't picked up on. In her usual two-fingered way, she typed up the story:

E

VEN THE

P

OSTCARDS IN

S

AIGON

D

EPICT

G.I.'s I

N

B

ATTLE

S

AIGON.

S

OUTH

V

IETNAM.

March 6âIt is a curious war. There are even colored picture postcards showing scenes of it.

They are sold in the lobbies of some of the expensive hotels and on the sidewalks of the downtown streets, where crowds of Vietnamese stroll and shop on weekends. Not many seem startled by the postcards, which are printed in Hong Kong and have captions such as “Direct hit” or “Mine detecting.” There is one called “Night

convoy moving cautiously” and another showing three American soldiers investigating a Vietcong trap, with a big arc of barbed wire in the foreground.

The Vietnamese prefer postcards with more sentimental themes and those that cost less money. But some American soldiers on leave in Saigon and the occasional visitor find it fun to send the war postcards home.

They usually show American soldiers in action, but one of Street fightingâone of the few depicting Vietnamese soldiersâhas a fairly brisk sale, according to a 14-year-old boy who works in a shop on Le Lol Street. He is not sure why, his own preference being for pictures of large cats or of fat, smiling, white babies. The Americans do not like them.

Gloria Emerson chose her words carefully to convey that bleakness she saw and felt. She was the best kind of writer, one aware that her words, though in print, must ring in readers' minds. Sometimes chunks of her work read like poetry when she repeated a phrase that established a rhythm. To read the opening lines of each paragraph was to grasp the whole story, as in her article about a medevac crew that helicoptered injured soldiers to the hospital, titled “On Med-Evac Copter, Faces and Pain.”

“Last Thursday was a typical day for the crew,” one paragraph began.

“The first radio call for help was at 8 a.m.,” read the next paragraph opener.

“It was the day on which Specialist 5 John H. Parham died ⦔

“I was trying to stop the bleeding, but it was, like, say, hopeless ⦔

“It was the day when 40 South Vietnamese soldiers were mistakenly shot and wounded by an American aircraft ⦔

“It was the day when two Americans, one 21 and one 19, tripped their own anti-personnel mine ⦔

“The younger man had been given morphine ⦔

“The other man was conscious but did not make a sound ⦔

“At the hospital, surgery was performed almost immediately. The younger man's legs were amputated below the knee and the older one's right leg was amputated below the knee ⦔

Gloria interviewed peasants, refugees, captured soldiers, bar girls, and street kids. She wrote about “Sister 5” (of six children), the 11-year-old who sold Christmas cards because making money was more important than going to school. She talked with a Buddhist monk who, hoping to “build a truly sovereign nation, a democratic nation,” quietly campaigned against the reelection of South Vietnam's corrupt president, Nguyen Van Thieu. She interviewed imprisoned Vietcong, including women who fought for the Communist North. Once a Vietnamese woman looked at Gloria in her street clothes and ponytail and asked, “What is it?” She'd never seen an American woman.

Gloria also examined the lives of ordinary American GIs, the soldiers and airmen in Vietnam mostly because they'd been drafted. She went on patrol with the “grunts,” as soldiers were tagged during the war. She rode with troops in helicopters on their way to the jungle to engage the enemy, and she returned in UH-1 “Huey” utility choppers loaded with gravely injured young men. She watched one 20-year-old chopper pilot fly while keeping an eye on his precious, wounded cargo and talked with a broken-hearted medic whose best friend had been killed a week earlier.

There were others, the GIs who sported peace symbols and “FTA” (“fuck the army”) on their helmets, and those who used heroin openly in front of their officers. Some hated Asians, calling them by the racist term “gooks.” Another, a bitter 20-year-old

communications specialist, bore a “warrior sense of revenge” for his six buddies killed in “'Nam.'” All had stories to tell, and Gloria Emerson made it her job to get those stories out.

The United States had begun drawing down the number of troops in Vietnam a year earlier, a massive figure that had swelled to 543,000. The fighting seemed endless, and to many, pointless, but there was plenty of action for a war-weary military. In 1970, when Gloria got to Vietnam, the press was war-weary as well. Every afternoon, as they had for five years, newsmen and the handful of women reporters working out of Saigon gathered for the “Five O'Clock Follies,” the military's daily briefing. Few believed that the press conference was anything more than a joke without any kind of credibility. Frequently they tossed barbs and made fun of the hapless information officers tasked with the briefings. Highly skeptical that the army was going to say anything useful or unembellished, veteran reporters preferred to gather news themselves. They depended on their own sources to get the story straight.

In July 1970, Gloria's

Times

article revealed that the South Vietnamese government crammed political prisonersâeditors, students, and the likeâinto cramped “tiger cages” made of stone on the prison island of Con Son. Newsmen were refused entry, so Gloria got her story from a church worker who accompanied two US congressmen on a fact-finding tour of Vietnam. The news caused an uproar, embarrassed President Thieu, and added to antiwar sentiments in the United States. A few days later, Gloria interviewed one of the prisonersâhe'd been released, but his legs had withered to the point that he could not walk. Even later, she reported the news when the Thieu government expelled the man who had revealed the tiger cages in the first place.

Late that October, Gloria broke the news that an American general had received the army's Silver Star, a top honor, based

on a made-up story. Her lead, the opening paragraph to a damning report, gave the truth straight up:

F

ACTS

I

NVENTED FOR A

G

ENERAL'S

M

EDAL

By Gloria Emerson

Special to the

New York Times

S

AIGON,

S

OUTH

V

IETNAM,

O

CT.

20âThe United States Army has awarded a Silver Star for valor to a general in Vietnam based on a description of acts of heroism in Cambodia that were invented by enlisted men under orders.

The decoration was presented last Thursday to Brigadier General Eugene P. Forrester, who was then assistant division commanderâ¦.

An Army spokesman has said that General Forrester had not seen the citation and that the general did not know that enlisted men had used more imagination than facts to write it.

In December, Gloria journeyed to Nnhokat Ridge near the DMZâthe demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnamâto interview brand-new American soldiers who had been drafted into the army. Their armored vehicle had run over a mine, and now the raw newcomers had a superstition:

T

O

C

OMPANY

B, A

PRICOTS

S

UGGEST

D

EATH.

Private Hobbs has stopped eating the apricots in the C-rations because he wants to stay alive and unhurt. Most of the other enlisted men in his squad do the same. Nor will they let anyone who has eaten apricots ride on their vehicle.

“The day we hit the mine, a sergeant ate apricots,” Private Hobbs related. “If a guy eats apricots, he's not coming with us.” â¦

Because the men rarely see the enemy, a feeling of hopelessness has grown in the company. The ground is old ground, covered by other Americans in the same huge, heavy machines years ago, when some of the current crop were boys in school.

“It seems so futileâthese guys are not even fighting for a cause,” Specialist 4 Edmund Burke, a medic, said. “And I've only seen three dinks in six months.” “Dink” is slang for the enemy.