Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (16 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

The next draft was just as bad as the previous one, and I felt even worse, given all the effort that I put into it. Chris was defensive, and I began to despair of ever getting decent documentation for the toolbox. So I was suprised when he entered my cubicle a couple of days later, with a smile on his face.

"We've just made an offer to a new writer", he told, "someone who I think will do a much better job on the technical side of things, since she used to be a programmer. Her name is Caroline Rose. I'm going to assign her to the window manager documentation and see what you think."

The next week I sat down to meet with Caroline for the first time, and she couldn't have been more different than the previous writer. As soon as I began to explain the first routine, she started bombarding me with questions. She didn't mind admitting it when she didn't understand something, and she wouldn't stop badgering me until she comprehended every nuance. She began to ask me questions that I didn't know the answers to, like what happened when certain parameters were invalid. I had to keep the source code open on the screen of my Lisa when I met with her, so I could figure out the answers to her questions while she was there.

Pretty soon, I figured out that if Caroline had trouble understanding something, it probably meant that the design was flawed. On a number of occasions, I told her to come back tomorrow after she asked a penetrating question, and revised the API to fix the flaw that she had pointed out. I began to imagine her questions when I was coding something new, which made me work harder to get things clearer before I went over them with her.

Initially, we distributed the raw documentation to developers piecemeal, as it was written, but eventually we wanted to collect it into one definitive reference called "Inside Macintosh". It was almost 1000 pages long, spread across three volumes, mostly written by Caroline with help from Bob Anders, Brad Hacker, Steve Chernicoff and a few others. Steve Jobs insisted on very high production standards for the first edition, naturally, using only the best binding and paper available. But high quality printing takes time, and the evangelists were impatient to get the definitive documentation out to developers as soon as possible.

I'm not sure whose idea it was, but a compromise was finally reached. Apple would publish a free, soft-bound "promotional" edition of Inside Macintosh on low quality paper as soon as possible, and send a copy for free to every developer. It was about as thick and flimsy as the Yellow Pages, so it became known as the "phone book" edition. Most developers still bought the high quality, beautiful hardback edition when it came out a few months later, anyway.

Invasion of Texaco Towers

by Jerry Manock in June 1982

Joan Baez

The Macintosh Team was sworn to the utmost secrecy about our project. We were moved to the top floor of a non-descript two story office building about two blocks from the established Bandley Drive Apple complex. There was no identification on our door. Our view west was of a Texaco gas station... thus the name "Texaco Towers" spontaneously evolved for the new Macintosh-in-development headquarters (see

texaco towers

). Steve Jobs would come over to visit us several times a day to stay on top of our progress. On these visits he alternated between "cheerleader" and "strict parent." Ever-present was his enthusiasm, his dedication to excellent design, and his exhortation to keep our project confidential.

The Jef Raskin Macintosh hardware concept was of a "portable" computer with a keyboard that rotated up to cover and protect a small rectangular CRT screen next to the floppy disk drive. One day Steve came bounding through our Texaco Towers door to announce that the overriding theme was now "minimal footprint on a desk" instead of "portability." He had been to a mall over the weekend and had been looking at "appliances." This term was to have considerable marketing usage in the next few years. Terry Oyama and I immediately started sketching a design that had the CRT above the floppy disk drive and motherboard, which gave the desired smaller footprint. To avoid a boxy look with sharp edges we felt would be intimidating to the user, we employed radiuses on the side corners and a large chamfer on the back. Another goal of ours was to make the back of the computer (which we realized could, in fact, be facing a visitor to user's office) as aesthetically pleasing as the front. Terry and I had traveled to the Hanover (Germany) Fair previously and determined that this would be a radical departure from current practice. For a similar reason we always tried to deal with "cable management" in an aesthetic way instead of the common "rat's nest" still seen today behind EDP equipment. But I digress.

One afternoon, when the project was in its advanced stages, Steve burst through the door, unannounced, in an exuberant mood. He had two guests... Joan Baez and her sister, Mimi Farina. Steve had been to lunch with them nearby and apparently could not contain himself when Joan asked him for advice on which computer to buy for her son, Gabe. Not only did he tell them about our Macintosh-in-development but he decided to SHOW it to them too. We sat there doubly dumfounded at the disclosure of our secret project to an outsider... who happened to be a huge celebrity... that we actually got to meet! Hopefully Steve had them sign a non-disclosure agreement, but I never saw it.

This was not the last time we saw Joan Baez. Steve invited her to an Apple Macintosh Black Tie "Christmas" party one February at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. I have a vivid memory of being on the dance floor with my wife, waltzing between dinner courses to the music of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, and bumping into Joan and Steve as they went swirling by. Apple sure knew how to throw a party!

Alice

by Andy Hertzfeld in June 1982

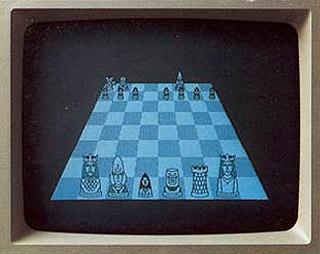

Alice's initial screen

Even though Bruce Daniels was the manager of the Lisa software team, he was very supportive of the Mac project. He had written the mouse-based text editor that we were using on the Lisa to write all of our code, and he even transferred to the Mac team as a mere programmer for a short while in the fall of 1981, before deciding that he preferred managing for Lisa. He would sometimes visit us to see what was new, but this time he had something exciting to show us.

"You've got to see the new game that Steve Capps wrote", he told me while he was connecting his hard drive up to my Lisa. He booted up into the Lisa Monitor development system, which featured a character-based UI similar to UCSD Pascal, and launched a program named "Alice". Steve Capps was the second member of the Lisa printing team, who started at Apple in September 1981. I had seen him around but not really met him yet.

The screen turned black and then, after a few seconds delay, a three dimensional chess board in exaggerated perspective filled most of the screen. On the rear side of the board was a set of small, white chess pieces, in their standard positions. Suddenly, pieces started jumping into the air, in long, slow parabolic arcs, growing larger as they got closer.

Soon there was one specimen of each type of piece, all rather humanoid looking except for the tower-like rook, lined up on the front rank of the board, waiting for the player to click on one to start the game. The player would be able to move like the piece they chose, so it was prudent to click on the queen, at least at first.

The pieces jumped back to their natural positions on the far side of the board, and an image of a young girl in an old fashioned dress floated down to the front row, which represented Alice from Lewis Carroll's "Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass" books, drawn in the style of the classic John Tenniel illustrations. The player controlled Alice and viewed the board from her perspective, facing away from the player so you only saw her from the rear.

A three digit score, rendered in a large, ornate, gothic font, appeared centered near the top of the screen, and then the game began in earnest, with opposing chess pieces suddenly leaping into the air, one at a time, in rapid succession. If you stood in one place for too long, an enemy piece would leap onto Alice's square, capturing her and ending the game.

It didn't take long to figure out that if you clicked on a square that was a legal move, Alice would leap to it, so it wasn't too hard to jump out of the way of an enemy piece. And, if you managed to leap onto the square of another piece before it could move out of the way, you knocked it out of action and were rewarded with some points. You won the game if Alice was the last one standing.

I was impressed at the prodigious creativity required to recast "Through The Looking Glass" as an action-packed video game that was beautiful to behold and fun to play. Alice was also addicting, although it took some practice to be able to survive for more than a few minutes. Obviously, we needed to have it running on the Mac as soon as possible.

Bruce Daniels seemed pleased that we liked the game. "Capps could probably port Alice to the Mac", he said, anticipating what we were thinking. "Do you think you could get him a prototype?"

Everyone agreed that we should get Capps a Mac prototype right away. I accompanied Bruce Daniels back to the Lisa building (where the rules required that non-Lisa employees be escorted by a Lisa team member), and I finally got to meet Steve Capps, who seemed easy-going and friendly, with a self-deprecating sense of humor. Later that afternoon, he visited Texaco Towers and I gave him the prototype and answered a few questions about the screen address and the development environment. He assured me that it wouldn't take that long to port.

Two days later, Capps came over to present us with a floppy disk containing the newly ported Alice game, now running on the Macintosh. It ran even better on the Mac than the Lisa, since the Mac's faster processor enabled smoother animation. Pretty soon, almost everybody on the software team was playing Alice for hours at a time.

Alice's packaging

Within a few weeks, I must have played hundreds of games of Alice, but the most prolific and accomplished player was Joanna Hoffman, the Mac's first marketing person. Joanna liked to come over to the software area toward the end of the day to see what was new, and now she usually ended up playing Alice for longer and longer periods. She had a natural talent for the game, and enjoyed relieving work-related stress by knocking out the rival chess pieces. She complained about the game being too easy, so Capps obliged by tweaking various parameters to keep it challenging for her, which was probably a mistake, since it made the game much too hard for average players.

Steve Jobs didn't play Alice very much, but he was duly impressed by the obvious programming skill it took to create it. "Who is this Capps guy? Why is he working on the Lisa?", he said as soon as he saw the program, mentioning Lisa with a hint of disdain. "We've got to get him onto the Mac team!"

But the Lisa was still months away from shipping, and Capps was needed to finish the printing software, so Steve wasn't able to effect the transfer. One weekend Capps ran into Steve Jobs in Los Gatos and was told, "Don't worry, the Mac team is going to nab you!" Finally, a compromise was reached, that allowed Capps to transfer over in January 1983 after the first release of the Lisa was completed.