Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (13 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

We all gathered around as Chris showed the calculator to Steve and then held his breath, waiting for Steve's reaction. "Well, it's a start", Steve said, "but basically, it stinks. The background color is too dark, some lines are the wrong thickness, and the buttons are too big." Chris told Steve he'll keep changing it, until Steve thought he got it right.

So, for a couple of days, Chris would incorporate Steve's suggestions from the previous day, but Steve would continue to find new faults each time he was shown it. Finally, Chris got a flash of inspiration.

The next afternoon, instead of a new iteration of the calculator, Chris unveiled his new approach, which he called "the Steve Jobs Roll Your Own Calculator Construction Set". Every decision regarding graphical attributes of the calculator were parameterized by pull-down menus. You could select line thicknesses, button sizes, background patterns, etc.

Steve took a look at the new program, and immediately started fiddling with the parameters. After trying out alternatives for ten minutes or so, he settled on something that he liked. When I implemented the calculator UI (Donn Denman did the math semantics) for real a few months later, I used Steve's design, and it remained the standard calculator on the Macintosh for many years, all the way up through OS 9.

And Another Thing...

by Andy Hertzfeld in March 1982

By early 1982, the Macintosh was beginning to be acknowledged as a significant project within Apple, instead of a quirky research effort, but it still remained somewhat controversial. Since the Mac was sort of like a Lisa that was priced like an Apple II, it was seen as potential competition from both groups. Also, our leader Steve Jobs had a habit of constantly boasting about the superiority of the Mac team, which tended to alienate everybody else.

Larry Tesler, who came to Apple from Xerox PARC in the summer of 1980, was the manager of the Lisa Application Software team. He understood and appreciated the potential of the Macintosh and was very supportive of the project. He was concerned that some of the Lisa team didn't share his enthusiasm, and thought that it would be helpful for us to demonstrate the Mac to his team and talk about our plans with them. He arranged for Burrell Smith and me to give a demo during a lunch-time meeting.

By this point, we had stand-alone Macintosh prototypes that no longer depended on an umbilical cord to a hosting Lisa. We didn't have the real plastic cases yet, but we were able to house the prototypes in plastic boxes of around the same size that were a passable imitation. The demo software environment was based on the "Lisa Monitor", a simple operating system cooked up by one of the main Lisa architects, Rich Page, that I got running on the Macintosh. The monitor was based on the UCSD Pascal system Filer and offered a simple, menu-based UI. We were able to boot the Mac into the monitor from an Apple II floppy, and then use it to launch various demo programs.

Burrell and I set up the prototype in a large conference room in the Lisa building. The Lisa applications team was seated around the table, but quite a few other Lisa team members had also gathered around, standing room only, perhaps twenty-five people in all. Larry Tesler gave us a nice introduction, and then we booted up the prototype and started to run through various demos while explaining the capabilities of the machine. Everything seemed to be going well, when suddenly there was a loud, insistent knock at the conference room door.

Before anyone could respond, the door was flung open, and in strode Rich Page, the systems wizard who was one of the main designers of the Lisa. Rich was a tall, bearded, ursine engineer, equally adept at hardware and software, who was responsible for getting Lisa to use the 68000, and had personally ported or created many of the tools that both the Macintosh and Lisa teams were using. But I had never seen him looking as angry as he was at the moment.

"You guys don't know what you're doing!", he began to growl, obviously in an emotional state of mind, "The Macintosh is going to destroy the Lisa! The Macintosh is going to ruin Apple!!!"

Burrell and I didn't know how to respond, and neither did anyone else in the room. Larry Tesler gave me an embarrassed glance, trying to figure out what to do. But Rich wasn't particularly interested in a response, he just wanted to vent his frustration.

"Steve Jobs wants to destroy Lisa because we wouldn't let him control it", Rich continued, almost looking like he was going to start crying. "Sure, it's easy to throw a prototype together, but it's hard to ship a real product. You guys don't understand what you're getting into. The Mac can't run Lisa software, the Lisa can't run Mac software. You don't even care. Nobody's going to buy a Lisa because they know the Mac is coming! But you don't care!"

With that, he turned around and strode out of the conference room, as quickly as he had come in. He slammed the door as he left, with the noise reverberating ominously in the stunned silence. There was some nervous laughter, but nobody knew what to say. Larry Tesler started to apologize, explaining that Rich didn't speak for most of the Lisa team, when suddenly the door was flung open again and Rich Page was back, just as angry as before.

"And another thing...", he said, before pausing to look directly at Burrell and myself. "I don't have any problem with you, I know it's not your fault. Steve Jobs is the problem. Tell Steve that I think that he's destroying Apple!" Once again, he turned around and left abruptly, slamming the door for a second time. We steeled our ourselves, wondering if he was going to return for a third round.

But this time, Larry was able to finish apologizing, and then we finished the demo quickly and held a brief question and answer session, with everyone still a bit shell-shocked from the unexpected outburst. We told Steve Jobs about Rich Page's oration later that afternoon, and he just shrugged, "That's Rich Page for you. He'll get over it."

The next morning Bill Atkinson called and told me that Rich Page felt bad about what happened and he wanted to take Burrell and me out to lunch to apologize. So that afternoon, the four of us went out for a long lunch, where Bill explained that Rich was just trying to do what he thought was right, and he didn't intend to get so emotional. Rich told us that he really appreciates that Burrell and I were doing great work for the company, but he was frustrated that Steve was such a loose cannon, and wasn't working for our mutual success. We left on decent terms, but in the back of my mind I was still worried that such obvious resentment would be a problem for us in the future.

Rosing's Rascals

by Andy Hertzfeld in March 1982

By the spring of 1982, the Lisa User Interface was finally settling down, and the software team was working feverishly to get everything ready to ship by their deadline in the fall. Most of the applications were shaping up, although myriad problems remained, and the team could finally sense a glimmer of light at the end of the long tunnel.

Dan Smith and Frank Ludolph were working on the Lisa Filer, the key application that managed files and launched other applications. It was beginning to come together, but Dan was still unsatisfied with the current design.

The Filer was based on a dialog window that prompted the user to select a document from a list, and then select an action like "Open", "Copy" or "Discard", and then answer more questions, depending on the selected action. There was so much prompting that it became known as the "Twenty Questions Filer". Dan thought that it wasn't easy or enjoyable to use, but there just wasn't enough time left in the schedule for further experimentation, so they were pretty much stuck with it.

One afternoon, Dan mentioned his dissatisfaction to Bill Atkinson, the main designer of the Lisa User Interface. Bill suggested that they meet that evening at his home in Los Gatos for a brain-storming session to see if they could come up with a better design, even though it was probably too late to use it for the initial release.

Bill favored a more graphical approach, and wanted to use small graphical images to represent files, which could be manipulated by dragging them with a mouse. He remembered an interesting prototype that he saw at M.I.T. called Dataland, where data objects could be spatially positioned over a large area. He adapted the idea for Lisa, allowing icons representing files and directories to be positioned on a scrolling, semi-infinite plane.

After a couple of nights of fiddling around, Dan and Bill had an interesting mock-up going, with icons representing documents and folders, complete with a trash can with flies buzzing around it. The icons used a mask bitmap to define their borders, so irregular shapes could be rendered seamlessly on the gray desktop. The new design seemed to have the simplicity and elegance that they were striving for, so they began to get excited.

They were both eager and afraid to show the mock-up to the rest of the team, since the design of the Filer was supposed to be frozen, and embarking on such a major revision would surely slip the schedule, which was already precariously close to unrealizable. They gathered up their courage and approached Wayne Rosing, the Lisa Engineering Manager, and explained their dilemma.

Wayne appreciated the potential of the new approach, but wasn't ready to slip the schedule to accommodate it. He thought it was perhaps barely possible to go with both the new design and the current schedule, if they could turn the mock-up into a solid working prototype in record time. He proposed a deal: he gave them permission to work on the new design in secret for the next two weeks. If they had a robust, stable prototype by then, he promised to support it. If they didn't, Bill and Dan promised to forget it and work to finish the earlier design.

Wayne extracted one additional promise from Bill: under no circumstances was he to show the mock-up to Steve Jobs. Wayne knew that Steve would have a strong reaction and would probably wreak havoc with the schedule accordingly. He didn't want Steve to see it until they knew if they could pull it off.

Bill was used to showing off his latest advances to the Mac team, and this new, icon-based approach to file management was a particularly important one. Bruce Horn had started working on the Mac team the previous month, and he was already starting to develop our file manager, which Bud had christened "The Finder". Bruce had similar ideas about spacial filing, and he and I had created a prototype called the "micro-finder" which represented files as tabs that were spacially organized on a picture of a diskette. Bill thought it was important for us to see the new direction as soon as possible, so he left us a copy of his prototype, under strict instructions not to show it to Steve.

We had a few close calls over the next couple of weeks as we played with the prototype, frantically quitting it when we heard Steve approaching. Finally, on the last day before the deadline expired, we must have cut it too close, because Steve knew that we were hiding something from him. We explained our promise to Bill, but Steve still demanded to see it, so we had to show it to him. He immediately fell in love with it, and ran off to talk to Bill and Wayne about it, just as we feared.

Luckily, the development had gone well the last two weeks, and Wayne was ready to commit to the new approach and unveil it to the entire team. He called an all-hands meeting, to which Bill, Dan, Frank and Wayne wore newly minted T-Shirts labeled "Rosing's Rascals". Wayne explained the surreptitious nature of the two week effort to the team while Bill set up the demo. Rosing's rascals had pulled it off, endowing the Lisa with a much more intuitive file manager that quickly became a hallmark of Apple's new user interface.

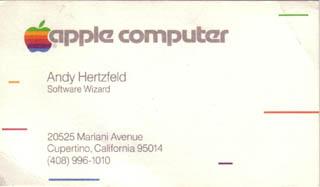

Software Wizard

by Andy Hertzfeld in March 1982

By the spring of 1982, the Macintosh project was considered more legitimate within Apple. It was beginning to transition from a research effort into a mainstream project. We had to get more organized as the team grew.

Initially, we didn't have formal titles in the Mac group, but we needed to figure out what they were in order to get business cards made. My title with the Apple II group was "Senior Member of Technical Staff", which sounded dull to me. I told Peggy Alexio, Rod Holt's secretary, who was ordering the business cards, that I didn't want any, because I didn't like my title.

The next day Steve came by and told me that he heard that I didn't want business cards, but he wanted me to have them, and he didn't care what title I used; I could pick any title that I liked. After a little bit of thought, I decided on "Software Wizard", because you couldn't tell where that fit in the corporate hierarchy, and it seemed a suitable metaphor to reflect the practical magic of software innovation.

When I told Burrell about my new title, he immediately claimed "Hardware Wizard" for himself, even though I discouraged him, since it diminished the uniqueness of my title. And, as soon as word got around, lots of other folks on the Mac team started to change their titles to something more creative. The trend persisted at Apple for many years, and even spread to other companies, but as far as I know, that's how it got started.