Riding Barranca (26 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

We learn that Neemsha is one in a long line of horse trainersâhis father and grandfather before him had been the horsemen of the palace. This little man with bad teeth

and shining eyes plays polo and races and trains. “I can do anything with horses,” he tells us.

At the hotel desk, I ask the concierge if we can get a tour of the palace stable nextdoor. “I am writing a book about riding,” I tell her, and that does the trick. Within minutes, Neemsha returns in a long, clean white shirt and crimson turban, instantly transformed, ready to give us a tour right from the front of our hotel. Lizbeth and I both climb into the back of the carriage, and off we go through the now open gate. As we cover the grounds on a soft dirt path that circles the gardens, our driver points out various trees and plants along the wayâfragrant jasmine and formal roses. Peacocks roam, and palm trees sway.

Neemsha then suggests that I climb up front into the driver's seat and take the reins, calling out

“Chella!” (let's go)

to his stallion. The horse begins to pace and then breaks into a canter. Still, he is not difficult to hold. We pull up beneath the

porte cochere

of the Palace Hotel where we are invited to enter. As we cross the marble entryway, there seem to be more servants in traditional attire than hotel guests.

You can arrange to have a private dinner for two on the massive expanse of lawn and watch your own private fireworks display. But with over four-hundred festivals a year in Varanasi, it hardly seems necessary to add to the

diwali

excitement where the cacophony of explosions is enough to set off anyone's startle response. The Varanasians appear to have a bubbling sense of joy, harmony, and balance, coupled with amazing immune systems, able to survive and flourish amidst the unsanitary conditions.

Driven back to our lesser hotel in this regal antique carriage, the white stallion imperiously takes a big dump at the front door as we jump out and tip our smiling driver.

The Stadium

Camels and fabulous horses are spread out amongst this primitive tent city, covering acres and acres of rolling pasture. We meander through a herd of water buffalo with their low-moaning calls, until we come to the horses, many of them tethered by all four feet so they can't kick out. Most of the horses look well cared for, with the exception of the occasional emaciated mare. There are a lot of young Marwaris for sale, often standing by their mothers' side. Camel-cart taxis pass us everywhere, and feral gypsy children try to get money from us, cursing us when we do not produce a coinâ

unnerving.

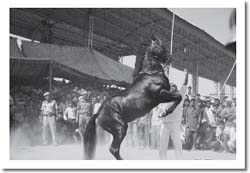

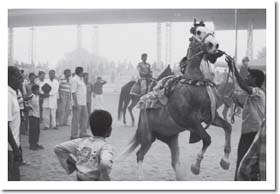

We finally come upon the big arena where a few men are trying out horses on thick, cloth pads set very far back, making their horses go into high-speed running walks, at least as fast as a flat-out gallop. The riders sit perfectly still. This four-beat

revaal

gait is incredibly smooth, even at this speed.

One magnificent pinto stallion is the most remarkable creature, very high strung, not used to all this commotion, but his handler is managing him somehow. Undoubtedly there are

plenty of mares in heat in the surrounding area, and it must be making him crazy.

We buy several colorful cotton halters with dangling strips and pom-pom top-knots, haggling over the price of each item. But carrying a plastic bag marks me for other people hawking stuff. These young men persist, trying to bargain with me over something I clearly don't want. I am forced to be rudeâ“NO, I wouldn't want that even if you gave it to me!”

Pinto

Excited about our trail ride on the following morning, we walk back to Camp Bliss and relax before dinner. The dining tent is lovely, made out of a warm amber-colored Indian print material. The food is all vegetarian, delicious, but there is no alcohol allowed in the holy city of Pushkar. I could use a glass of wine.

Tiny lights are strung all over the gooseberry trees, which makes the place especially magical at night. Two comfortable canvas lounge chairs are placed outside of each sleeping tent. You can sit and listen to the evening drumming and watch the nightly entertainment of dancers, fire eaters, and jugglers

who perform around the bonfire. We go to bed early, all set to rise for our ride, so long in the planning.

The equestrian tent camp, ten minutes away, is a rather miserable setup compared to the relative luxuries we have been enjoying at Camp Bliss. The horses are tethered out in individual spots, and I am curious to know which horse I will get. They all seem relatively small and thin. I just hope there is a good saddle left for me as all the other riders arrived the afternoon before and they have already gotten their horses and tack and taken a preparatory ride. We sit around a grubby, bare table with a few other womenâmostly Germansâone of whom asks in a heavy accent, “Do you like to gallop?”

“Well, sometimes,” I respond.

“Goot,” she says, “then you are accepted.”

There is one pleasant, young woman who is going to ride the owner's horse that morning, because the mount she'd originally been given was not appropriate for her. I wonder if my scrawny little mare, Angelie, will be comfortable, for she is as narrow as a skiff, and the saddle I receive is much too small. The metal rim embedded in the low cantle hits me at my coccyx, and while this does not seem to be a problem at first, it soon becomes painful. I try to remedy the problem by lengthening my stirrups, which could be a mistake.

Red ribbons are tied to most of the mares' tails, indicating they are kickers. I am told that Angelie is a “lead horse” and very fast despite her size. The leader of the morning ride is a handsome twenty-nine-year-old named Manu.

We go out into the desert where the landscape is strangely similar to Arizona, but very hot and humid. The trail we take is deep with soft, golden-brown earth. At least if anyone falls, they will be received by fortunate footing. But all of the horses seem to ride together in a clump, and while Manu keeps

waving me back, indicating that I should stay away from his mare, I soon find that my horse has a very tough mouth and is extremely difficult to restrain. Undoubtedly, she has had so many riders pulling on her, trying to stop her from racing, that she has become unresponsive. Even while walking, the iron-rimmed cantle is jamming into me as Angelie bounces up and down, prancing sideways, wanting to go. I don't want to be a complainer, but the stirrup leathers are pinching the insides of my knees and it's beginning to seriously hurt. But this discomfort is nothing compared to what I feel once Manu suddenly gives the signal to

GO!

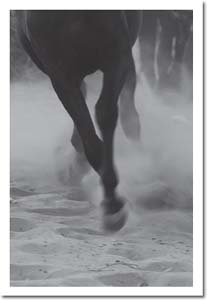

Then, the whole tight pack lights out at a dead-bolt run.

Desert Dust

Trying to hold my horse back from ramming into his, Angelie goes into a very choppy gait that makes me bounce in the saddle so that the stirrup leathers, snapping open and shut, are cutting into me like razors. We take several turns at full

speed, and she almost slips. If she fallsâI thinkâI will get trampled by the horses flying so close behind. I cannot believe the pace we are going with little preparation for this.

I worry about Lizbeth, who is somewhere toward the back of the pack. She must be riding in a cloud of dust, unable to breathe. Once we stop for a moment, before another burst of speed, some of the other riders request that we change order so that they can ride farther up front, out of the dust.

I'll change places with you, I think, if you'll trade horse and saddle!

I wonder if I can ride like this for days. It feels as if there is nothing between my legs. When I mention the stirrup leathers, Manu seems unconcerned. We soon take off on another high speed tear. I try to relax, but the stirrup leathers are really eating into me. When we stop, I turn toward the back of the group and ride up to Lizbeth, saying in a whisper, “I think we should cancel.”

“I'm so glad to hear you say that,” she exclaims. “I was definitely going to drop out, and I was wondering what I would do, as I figured you'd just plow ahead.”

“I've never been so uncomfortable on a horse in my life,” I respond. “I feel like we might get seriously injured. It's just not worth it.”

“Plus, it's not good for the horses,” Lizbeth adds, “Flat out racing, everyone out of control.” Lizbeth is a terrific rider who has been in dressage training for fifteen years. She recently imported a fabulous young Andalusian from Seville, Spain. Her final words on the subject of this rideâ“I

am so out of here!”

We both agree that we should call our travel agent, and try to do something else.

On returning to the disgusting tent-camp bathroom, I look at the inside of my legs and see that I am covered in raw, bruised marks. If I were to continue, I would probably end up bleeding.

I think about my tendency to always “plow ahead.” I guess that had always been my way, to keep on going, to overachieve, to try and be the fastest and the best, partly my temperament and partly the way I was brought up. “I don't care what you do,” my father once told me, “as long as you are number one.” That was a heavy requirement to put on a small child.

We were expected to be self-reliant, independent, resilient in the face of torment, getting back in the saddle after being knocked off. Our father would lead across whitewater, down muddy embankments, even down the middle of railroad tracks, as if our uneasiness was titillating for him.

Once Popi even went so far as to spray bug repellent in the face of Cia's horse while she was holding baby Abigail. The horse reared and Abigail fell. I'm sure he felt remorse, but why was he being so careless?

My father often put me in uncomfortable situationsâ riding into a bull pasture with a bull whip in hand while I rode my pony. That created anxiety in me, an anxiety that is still beginning to surface, as I try to control situations so that I won't be late or panicked, having a somewhat compulsive need for daily ritual, becoming more reliant on habit.

My friends think of me as a fearless rider, but that is no longer true. As a child, one goes along with the program, rarely questioning, but now as an adult, I can weigh the risks and say, “No, I do not want to do this.”