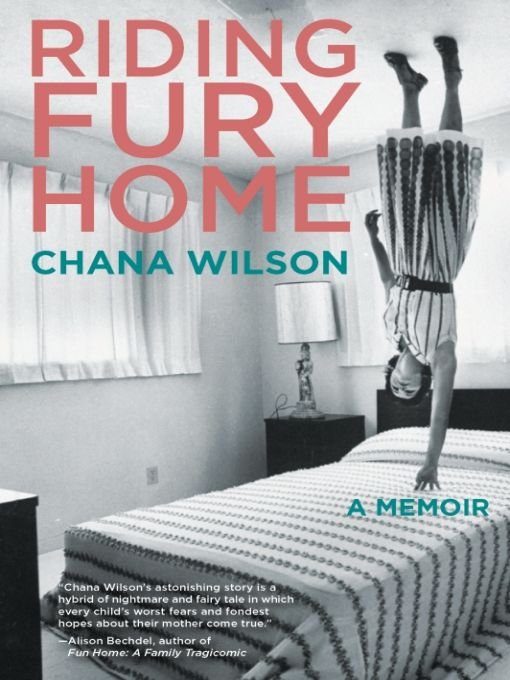

Riding Fury Home

Authors: Chana Wilson

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

For Danaâbrilliant thinker,

advocate for justiceâmy love always.

advocate for justiceâmy love always.

“Whatever is unnamed, undepicted in images, whatever is omitted from biography, censored in collection of letters, whatever is misnamed as something else, made difficult-to-come-by, whatever is buried in the memory by collapse of meaning under an inadequate or lying languageâthis will become, not merely unspoken, but unspeakable.”

âAdrienne Rich,

On Lies, Secrets, and Silence

On Lies, Secrets, and Silence

Â

Â

Until I was twenty five, my first name was Karen. Chana, my Hebrew name, in English is pronounced Hah-nah.

PART ONE: MILLSTONE, NEW JERSEY

Chapter 1. White Plains

I WAS THE FIRST CHILD ever allowed to visit a patient at the private mental hospital where my mother was being treated. Before our first trip there, Dad said, “The doctors think your mother will get better if she can keep seeing you.”

Visiting hours were on Sundays, so I had to drop out of Jewish Sunday school, which I had just begun six months earlier. Though I was seven, they had put me with the six-year-olds because I didn't read any Hebrew. The odd-shaped letters blurred before my eyes, and I made no attempt to decipher them. But I loved the singing, humming along to the guttural language. On the easy songs, like “Hava Nagila,” I belted the words. After songs, we got to eat exotic treats: dates, figs, and rugelachâbuttery spirals of dough with raisins and cinnamon.

My father and I sang on the two-hour drive to the hospital, up the New Jersey Turnpike, over the Tappan Zee Bridge. He taught me his favorite:

“I'll build a bungalow, big enough for two, big enough

for two my honey, big enough for two, and when we're married, happy we'll be, under the bamboo, under the bamboo tree.”

Dad and I sang and sang: ballads, show tunes, and spirituals, as our old brown Hudson lumbered along.

“I'll build a bungalow, big enough for two, big enough

for two my honey, big enough for two, and when we're married, happy we'll be, under the bamboo, under the bamboo tree.”

Dad and I sang and sang: ballads, show tunes, and spirituals, as our old brown Hudson lumbered along.

Going to see my mother who was not a mother. My need of her was frozen, clamped down against any thaw. But she needed me. Maybe if I loved her enough, my mother would heal.

Â

Â

I REMEMBER THE GROUNDS, the front lawn an expanse of green with a curving drive. The visitors gathered outside the front entrance, waiting for the appointed hour. The gates were locked until then, and there was a quiet hush among us, the waiting families. Dad held my hand. In my imagination, the buildings are dark and gothic, hovering like some dragon ready to pounce.

That first timeâand every Sunday afterwardâI met my mother at the foot of a stairwell. As she came down the stairs, I looked up at her face, puffy and sallow. She leaned over to hug me, and I reached up my arms, willing myself not to pull away, but I flinched a little. She took my hand and we ambled onto the back lawn, my father trailing behind. Mom moved slowly, and she stumbled now and then. We walked past the tennis courts. “Fancy schmancy, huh?” Mom said. Then she laughed, but it didn't sound happy. I knew Mom tried to play. She told me that all the patients were on so many drugs that they missed a lot of balls.

I always brought Happy, my favorite stuffed animal, with me. One day, Mom and I were sitting on some steps outdoors, when another patient came over. He leaned over and put his face close to mine. I could smell his foul breath. He pointed at Happy. “What a nice bunny!” Happy's long, floppy ears must have misled him.

“He's not a bunny, he's a dog!” I protested, in an outburst of anger that was taboo to express around my mother. She was sick, it was not her fault, and I knew I must not get angry at her.

Mom put her hand on my back. “It's okay, honey,” she said. The man scowled at me, turned abruptly, and stormed away.

Â

Â

ONE TIME, MY FATHER had a meeting with my mother's psychiatrist while I waited in the car. I watched him walk back, hands in his pockets, head down. He got in, sat behind the steering wheel, put his face in his hands, and wept. Then, finally, he said, “The doctor says your mother will never get well. He says she is incurable.” I looked down at my hands. Happy had dropped to the floor. Somewhere inside I knew I must not be doing a good enough job.

On winter days the hospital gave my mother a pass, and we went into town. We always went to the movies. I remember seeing Peter Sellers in

The Mouse That Roared,

a zany film about a tiny country that invades America

.

In that dark cinema, I could enter another world and forget the bloated stranger called Mother who sat beside me.

The Mouse That Roared,

a zany film about a tiny country that invades America

.

In that dark cinema, I could enter another world and forget the bloated stranger called Mother who sat beside me.

After the movies, we always went to a local steak house, and the three of us ordered the same thing: T-bone steak with french fries. How I lived for the dessertâparfait in a tall glass, layers of vanilla ice cream and frozen strawberries in syrup, gleaming red and white. I would spy the parfait on other diners' tables, anticipating its soft, tart sweetness in my mouth.

Chapter 2. Before She Left

BEFORE SHE LEFT, MY MOTHER read to me. Hundreds and hundreds of my mother's books lined the shelves of our living room in the house we'd moved into when I was five. Mom would pull the book of Greek myths down from the shelf. How I loved those stories: Arachne in the guise of a spider weaving her web, Icarus flying toward the sun until his wings melted. Sometimes, she would read me a paragraph in Latin. I loved the cadence of my mother's voice, first the Latinâwhich seemed so foreign and mythicâand then her English translation.

My mother sprinkled her speech with bits of other languages: the Yiddish primal cry of woeâ

Oy gevalt!Vay is mir!

âdelivered with a melodramatic wringing of hands; the German she had learned as a scientist; and her love, French. She had a French ditty that she often said to me, declaimed in a low alto with one hand fisted on her breastbone, one hand gesturing outward: “

Je t'aime, je t'adore. Que veux tu?Depuis encore!!!”

(She translated this for me as: “I love you. I

adore

you. What do you want? What more

is

there?”) Somehow,

even at five, I understood this wasn't about me, and wasn't about my father, but was directed to some mysterious, unnamed person.

Oy gevalt!Vay is mir!

âdelivered with a melodramatic wringing of hands; the German she had learned as a scientist; and her love, French. She had a French ditty that she often said to me, declaimed in a low alto with one hand fisted on her breastbone, one hand gesturing outward: “

Je t'aime, je t'adore. Que veux tu?Depuis encore!!!”

(She translated this for me as: “I love you. I

adore

you. What do you want? What more

is

there?”) Somehow,

even at five, I understood this wasn't about me, and wasn't about my father, but was directed to some mysterious, unnamed person.

My mother adored song: Opera was her first love, musicals second.When she played opera on the hi-fi, sometimes I felt like covering my ears, but after Mom took me to my first operaâ

Carmen,

at New York's City CenterâI would sing along with her, “

Toréador, en garde!Toréador! Toréador!”

imagining myself a bullfighter in a fancy gold-and-red jacket and that funny hat, waving my capeâ“Olé!”âas the bull charged.

Carmen,

at New York's City CenterâI would sing along with her, “

Toréador, en garde!Toréador! Toréador!”

imagining myself a bullfighter in a fancy gold-and-red jacket and that funny hat, waving my capeâ“Olé!”âas the bull charged.

In the afternoons, I would come home from kindergarten, and then first grade, filled with stories of my day. I chattered to Mom over a snack, showed her whatever I'd created in class. Then, I got to pick out one of our musicals,

My Fair Lady, Oklahoma,

or

South Pacific

, sitting at the dining room table, crayoning in my coloring book. Together, Mom and I would croon: “I'm gonna wash that man right outta my hair and send him on his way.”

My Fair Lady, Oklahoma,

or

South Pacific

, sitting at the dining room table, crayoning in my coloring book. Together, Mom and I would croon: “I'm gonna wash that man right outta my hair and send him on his way.”

All the words that were spoken, that my mother read and sang to me, left so many words unspoken. The silence of what was happening to her. The grief that was pulling her under. It wouldn't be until I was twenty that she would tell me the secret of her anguish, a secret whose impact would shape both our lives.

Â

Â

ONE DAY IN MAY OF 1958, just after my seventh birthday, my mother was gone. I didn't know that while I was at school she had gone into the bathroom and held my father's rifle to her head. I didn't know she'd pulled the trigger, and that, by some fluke, the rifle had jammed. All I knew was that my mother had been taken from me.

Years later, when I was an adult, my father told me about that day.

“I was in the kitchen, home from work for lunch, when I heard the clank of metal hitting the floor and your mother yelling, âShit! It didn't work!'”

My father ran to the hall outside the bathroom. My mother was no longer there, but his rifle lay on the floor. He knelt down and opened the gun. A round fell out. He picked it up and stared at where the firing pin had left a dent in the case.

“I thought,

Oh my God, she pulled the trigger!

I put the rifle down and called out, âGloria?' She didn't answer. But then I realized we were beyond talking now. I went to the phone and called her psychiatrist. âTake her to Carrier Clinic, Abe,' he told me. âI'll call ahead and arrange her admission.'”

Oh my God, she pulled the trigger!

I put the rifle down and called out, âGloria?' She didn't answer. But then I realized we were beyond talking now. I went to the phone and called her psychiatrist. âTake her to Carrier Clinic, Abe,' he told me. âI'll call ahead and arrange her admission.'”

After that, my father took over storytelling. At night, he lay next to me in my bed, mesmerizing me with his made-up tales. There were no Greek myths, but I loved his stories, too. One was about a white butterfly who is lonely and longs for friendship. He sees a white fluttering shape far away in a distant field and is drawn toward it, searching and searching. After a long journey, he reaches the shape. Ah, it's a lady butterfly. They fall in love and are both very happy.

A few days after my mother left, Dad explained, “The doctors are fixing Mom. It's her head, not her body, that is sick. She's in a special hospital for people just like her, called a mental hospital.”

Other books

The Brides of Chance Collection by Kelly Eileen Hake, Cathy Marie Hake, Tracey V. Bateman

The Bride Hunt by Jane Feather

Eyes in the Fishbowl by Zilpha Keatley Snyder

A Question of Upbringing by Anthony Powell

Hawk's Haven by Kat Attalla

Mindworlds by Phyllis Gotlieb

Her Warrior for Eternity by Susanna Shore

The Dead-Tossed Waves by Carrie Ryan

Devil's Playground by Gena D. Lutz