Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw (115 page)

Read Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw Online

Authors: Norman Davies

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

Article 8.

The above decree comes into force on the day of its publication.

Chairman of the KRN | Bolesław Bierut |

Chairman of the PKWN | Edward Osóbka-Morawski |

Director of the Office of National Defence | Michał Rola- |

A further decree dated 31 August 1944 listed the punishments, including the death penalty, to be applied to ‘fascist-Hitlerite criminals’ and ‘Traitors of the Polish Nation’. It defined such criminals and traitors as ‘anyone acting on behalf of the occupation authorities’ and ‘anyone acting against persons present in the confines of the Polish State’.

2

The political context of these decrees may be judged from the sentiments about the Warsaw Rising expressed in an Appeal circulated on 18 August 1944 under the auspices of the Central Committee of the Polish Workers Party (PPR):

‘A band of ruffians and lackeys from pre-war

Sanacja

and ORN circles is today raising its filthy paw against the Polish Army which is pursuing a heroic and selfless struggle for the freedom of the homeland. A handful of ignorant leaders of the Home Army, acting on the orders of [General] Sosnkowski and in the name of the threadbare political games of the

Sanacja

clique, have pushed the population of Warsaw into battle.’

3

George Orwell

‘As I Please’ (from

Tribune

, 1 September 1944)

It is not my primary job to discuss the details of contemporary politics, but this week there is something that cries out to be said. Since, it seems, nobody else will do so, I want to protest against the mean and cowardly attitude adopted by the British Press towards the recent rising in Warsaw.

As soon as the news of the rising broke, the

News Chronicle

and kindred papers adopted a markedly disapproving attitude. One was left with the general impression that the Poles deserved to have their bottoms smacked for doing what all the Allied wirelesses had been urging them to do for years past, and that they would not be given and did not deserve to be given any help from outside. A few papers tentatively suggested that arms and supplies might be dropped by the Anglo-Americans, a thousand miles away: no-one, so far as I know, suggested that this might be done by the Russians, perhaps twenty miles away. The

New Statesman

, in its issue of 18 August, even went so far as to doubt whether appreciable help could be given from the air in such circumstances. All or nearly all the papers of the Left were full of blame for the

emigre

London Government which had ‘prematurely’ ordered its followers to rise when the Red Army was at the gates. This line of thought is adequately set forth in a letter to last week’s

Tribune

from Mr G. Barraclough. He makes the following specific charges:

- The Warsaw rising was ‘not a spontaneous popular rising’, but was ‘begun on orders from the

soidisant

Polish Government in London’. - The order to rise was given ‘without consultation with either the British or Soviet Governments’, and ‘no attempt was made to coordinate the rising with Allied action’.

- The Polish resistance movement is no more united round the London Government than the Greek resistance movement is united round King George of the Hellenes. (This is further emphasised by frequent use of the words

émigré, soidisant

, etc., applied to the London Government.) - The London Government precipitated the rising in order to be in possession of Warsaw when the Russians arrived, because in that case ‘the bargaining position of the

émigré

Government would be improved’. The London Government, were are told, ‘is ready to betray the Polish people’s cause to bolster up its own tenure of precarious office’, with much more to the same effect.

No shadow of proof is offered for any of these charges, though 1 and 2 are of a kind that could be verified and may well be true. My own guess is that 2 is true and 1 partly true. The third charge makes nonsense of the first two. If the London Government is not accepted by the mass of the people in Warsaw, why should they raise a desperate insurrection on its orders? By blaming Sosnkowski and the rest for the rising, you are automatically assuming that it is to them that the Polish people looks for guidance. This obvious contradiction has been repeated in paper after paper, without, so far as I know, a single person having the honesty to point it out. As for the use of such expressions as

émigré

, it is simply a rhetorical trick. If the London Poles are

émigrés

, so too are the Polish National Committee of Liberation and the ‘free’ Governments of all the occupied countries. Why does one become an

émigré

by emigrating to London and not by emigrating to Moscow?

Charge No. 4 is morally on a par with the

Osservatore Romano’s

suggestion that the Russians held up their attack on Warsaw in order to get as many Polish resisters as possible killed off. It is the unproved and unprovable assertion of a mere propagandist who has no wish to establish the truth, but is simply out to do as much dirt on his opponent as possible. And all that I have read about this matter in the press – except for some very obscure papers and some remarks in

Tribune

, the

Economist

and the

Evening Standard –

is on the same level as Mr Barraclough’s letter.

Now, I know nothing of Polish affairs, and even if I had the power to do so I would not intervene in the struggle between the London Polish Government and the Moscow National Committee of Liberation. What I am concerned with is the attitude of the British intelligentsia, who cannot raise between them one single voice to question what they believe to be Russian policy, no matter what turn it takes, and in this case have had the unheard-of meanness to hint that our bombers ought not to be sent to the aid of our comrades fighting in Warsaw. The enormous majority of left-wingers who swallow the policy put out by the

News Chronicle

, etc., know no more about Poland than I do. All they know is that the Russians object to the London Government and have set up a rival organisation, and so far as they are concerned that settles the matter. If tomorrow Stalin were to drop the Committee of Liberation and recognise the London Government, the whole British intelligentsia would flock after him like a troop of parrots. Their attitude towards Russian foreign policy is not ‘Is this policy right or wrong?’ but ‘This is Russian policy: how can we make it appear right?’ And this attitude is defended, if at all, solely on grounds of power.

The Russians are powerful in eastern Europe, we are not: therefore we must not oppose them. This involves the principle, of its nature alien to Socialism, that you must not protest against an evil which you cannot prevent.

I cannot discuss here why it is that the British intelligentsia, with few exceptions, have developed a nationalistic loyalty towards the USSR and are dishonestly uncritical of its policies. In any case, I have discussed it elsewhere. But I would like to close with two considerations which are worth thinking over.

First of all, a message to English left-wing journalists and intellectuals generally: ‘Do remember that dishonesty and cowardice always have to be paid for. Don’t imagine that for years on end you can make yourself the boot-licking propagandist of the Soviet regime, or any other regime, and then suddenly return to mental decency. Once a whore, always a whore.’

Secondly, a wider consideration. Nothing is more important in the world today than Anglo-Russian friendship and cooperation, and that will not be attained without plain speaking. The best way to come to an agreement with a foreign nation is

not

to refrain from criticising its policies, even to the extent of leaving your own people in the dark about them. At present, so slavish is the attitude of nearly the whole British press that ordinary people have very little idea of what is happening, and may well be committed to policies which they will repudiate in five years’ time. In a shadowy sort of way we have been told that the Russian peace terms are a super-Versailles, with partition of Germany, astronomical reparations, and forced labour on a huge scale. These proposals go practically uncriticised, while in much of the left wing press hack writers are even hired to extol them. The result is that the average man has no notion of the enormity of what is proposed. I don’t know whether, when the time comes, the Russians will really want to put such terms into operation. My guess is that they won’t. But what I do know is that is any such thing were done, the British and probably the Americans would never support it when the passion of war had died down. Any flagrantly unjust peace settlement will simply have the result, as it did last time, of making the British people unreasonably sympathetic with the victims. Anglo-Russian friendship depends upon there being a policy which both countries can agree upon, and this is impossible without free discussion and genuine criticism

now

. There can be no real alliance on the basis of ‘Stalin is always right’. The first step towards a real alliance is the dropping of illusions.

Finally, a word to the people who will write me letters about this. May I once again draw attention to the title of this column and remind everyone that the Editors of

Tribune

are not necessarily in agreement with all that I say, but are putting into practice their belief in freedom of speech?

Comment:

Orwell’s principled stand is all the more remarkable given the patriotically charged atmosphere of wartime, when serious criticism of Britain’s Soviet ally was everywhere inhibited. None of the leading dailies took a similar stand. Apart from the Catholic

Tablet

and various Scottish publications that were influenced by the Polish troops stationed in Scotland, the left-wing

Tribune

was virtually alone in the strength of its concern for Warsaw. On 15 September, it published a letter from the political writer Arthur Koestler, who declared that the Soviet attitude to the Warsaw Rising was ‘one of the major infamies of this war which, though committed by different methods, will rank for the future historian on the same ethical level as Lidice.’

(P. M. H. Bell, ‘The Warsaw Rising’, in

John Bull and the Bear: British public opinion . . . and the Soviet Union, 1941–45

(London, 1990), p. 164.)

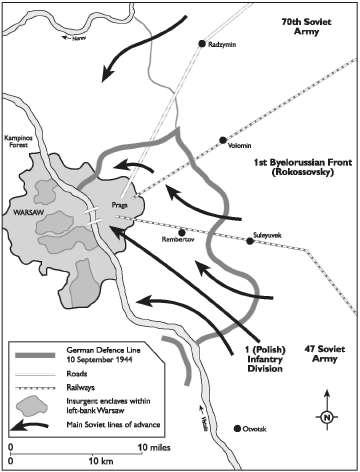

10–15 September 1944

16–23 September 1944

ymierski (General)

ymierski (General)