Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (18 page)

Q and I live less than a mile from the valley of the lower Missouri River where high bluffs of limestone are sprinkled with small mounds fifteen-hundred years old — that’s to say, structures from the time of Visigoths sacking Rome and Saxons doing similarly in Celtic Britain. In one place, before it got overtaken for a hunting tract owned by an outsider, was a mound I would visit to sit nearby and look across the two-mile floodplain toward the Missouri. When the mound was built, probably for a burial, the river flowed at the foot of the bluff.

Those mounds are where they are — I’m again speaking as a probabilist — because the people who made them believed a river could carry the great mystery within a human to another place on a presumed journey reflecting the provable one. Specific places lie at the heart of every Indian cosmology I know because human genesis arises from the land —

from a place.

To the indigenous people who lie within those mounds of earth and stone along the Missouri, a sense of the sacred began and ended with an earthen quoz pushing reverence into recognition of mystery.

While probabilists can do little more than postulate the possibility of a post-corporeal journey along a river, they can unquestionably make a verifiably veritable one (in what some “believers” consider our

pre

-afterlife). Over the years, from that mound above the river, I’ve imagined voyages departing there for distant shores, and I’ve even actually taken a few. From it, I could set my canoe upon the Missouri and — until the last few miles — using no power but what resides in rivers themselves, reach the Ouachita, a voyage of eleven-hundred miles. Wherever you are reading these words — Sydney, Nebraska, or Sydney, Australia; Florence, Oregon, or Firenze, Italy — the nearest floatable stream could start you too on a voyage to the Ouachita.

Once again, nimble reader (you who are so often ahead of me), you catch the drift. We belong to the land; the territories are one because the waters are one, and nothing so reveals that oneness as the courses of rivers. You know the old analogy: arteries and veins in a single body. I believe the ancient minds of America also understood this, and that’s the reason sources and junctures of waters were important to them, for it is, perhaps above all else, sources and junctures that create not just quoz but the sacred in any cosmology. I believe those intellects, like ours, comprehended existence, if a human is to comprehend it at all, through the discovery and honoring of connections and continuums.

These notions came into play soon after Q and I arrived in Catahoula Parish on a late-March Saturday afternoon in quest of, if you will, the “bottom” of the Ouachita at Jonesville, Troyville, Trinity — the last league of the river. The Louisiana state road dumped us onto U.S. 84 at the edge of town and its spread of outskirt businesses, perhaps only one older than Daffy Duck. It was the kind of place I call a ZONE: Zoning Ordinances Non-Existent. But the homely strip was somewhat ameliorated by Sonny’s, Home of the Italian Burrito, a rolled tortilla plump with fourteen ingredients more appropriate to a pizza than anything Mexican. For a five-spot, on two occasions, Q and I made a shared meal of one of them.

As we tried to reach the heart of Jonesville, population 2,700, my usually reliable seat-of-the-pants compass somehow went awry and caused me to misguess enough directions to create a tour of the village and its de facto, semisegregation. In the Negro section (we were soon to hear it called “Over the Tracks”), the citizens were outside in the mild air, gadding about, jollifying, getting ready for Saturday night; barbecue smokers scented the afternoon, voices called from porch to porch, coolers got stocked with ice and beverages. But in the white section, the doors were closed, shades drawn, stoops empty, and gadding about was nil; it could have been a January afternoon in northern Michigan.

By eliminating one direction after another, a brief task in such a small place, I eventually fumbled us into the historic center of Jonesville, the spot where it began. I am obligated to report what we saw, and that was considerable evidence of one of the poorest parishes in one of the poorest states. It reminded me of Gus Kubitzki’s description of another town to be unnamed here, “an agreeable place once it’s well behind you.”

The impoverished commercial buildings had a lone saving grace: there weren’t many of them. But those yet standing ranged from the crumbling, collapsing, and crippled to the decaying, deteriorated, and derelict. Remodeling meant boarding up a window and painting

KEEP OUT

across it. Here was another wreckage of that ship of state, the

U.S. American Dream,

that merchantman which founders and comes to grief whenever the winds in its sails — voracity without limits, profit without responsibility — inevitably slacken. Of the endeavors an impartial observer might honestly term “prosperous,” I saw only two: Catahoula Bank and, behind it, the Addictive Disorder Clinic, a proximity a novelist of Main Street America would have to avoid to keep from being accused of clangingly obvious symbolism.

As we walked, neither Q nor I said anything for some time. At last she broke the numbed silence. “It looks like a place that lost its soul.” Catahoula perish.

[

READER ALERT:

Although there is no bloodshed or vileness in it, this Huey Long Bridge story is only going to get darker, so I pause here for readers with heartstrings easily tightened to seek the refuge of chapter 20.]

A Grave History

T

HE DILAPIDATIONS

in the old mercantile heart of Jonesville could not entirely overcome — I don’t know how else to term it — an aura. Over several hours of trying to define it, I finally realized it arose from

what had been

— I don’t mean crumbling bricks and decaying wood; rather it came from something much older, something not yet fully eradicated. A long and deep human past will stain the land in ways beyond discolorations of soil and will leave a scent perceptible not to the nose but to the imagination.

My interest in Jonesville may have been similar to John Milton’s indubitable absorption with powers of destruction and evil in the face of salvation, an interest fully evident in his great, paired epic poems: not only is

Paradise Lost

a greater work, it’s five times longer than

Paradise Regained.

Or consider Dante’s unmistakable captivation not with the beatific souls in his

Paradiso

but with the tormented dead whirling in the

Inferno.

I hope you will tolerate — those of you who have not gone on to chapter 20 — my use here of the word

evil,

because what happened in Jonesville was wrong, although it was a wickedness having nothing to do with the more usual — to judge from our popular entertainments — murder and mayhem, knives and napalm. It was not an evil of weapons but of tools: spades, scoops, scrapers, steam shovels. It’s a tale of a past and a future that got, you could say, abridged.

On its ascent of the Ouachita in 1804, the Forgotten Expedition passed by what is today the historic center of Jonesville, and William Dunbar wrote in his log about a lone resident, a Frenchman whose “house is placed upon an Indian mount with several others in view: There is also a species of rampart surrounding this place and one very elevated mount, all of which I propose to view and describe on my return, our situation not now admitting delay.” In late January 1805, Dunbar did return to make the first record of one of the most spectacular constructions in the entire region of Mississippi Valley aboriginal earthworks. Even Hunter, usually attracted more to resources of future profit, said, “If one may judge from the immense labor necessary to erect those Indian monuments to be seen here, this place must have once been very populous.”

A couple of hundred yards below the crotch of the big Y that is the juncture of the Tensas with the Ouachita, at about the place where the little Catahoula River joins, once stood more than a half-dozen (observers gave varying numbers) prehistoric mounds protected on two sides by a large, defensive, L-shaped earthen embankment about a mile long running from the Black River to the Catahoula, with a pair of water gaps allowing dugouts to enter the enclosure. The right-angled rampart inversely reflected the juncture of those two rivers and protected the center. Rising near the middle was, to use a later name, the Great Mound, its height and structural design then unmatched among the large earthworks of the United States.

When the expedition came through, the Indians — both builders and later denizens — were long gone, and the only resident was the Frenchman who operated a ferry across the Black River. At the time, although Dunbar wouldn’t have known, the Great Mound was more than a thousand years old, an age commensurate with the First Crusade. It was also the second-highest native mound in America; only the huge Monk’s Mound at Cahokia, Illinois, across the Mississippi from St. Louis, stood taller, but just by a few feet. Because the Great Mound rose from a far smaller base, its steeply angled upper portion, Dunbar’s “cone,” created steep and high architectural lines probably found nowhere else in the United States. Despite being heavily overgrown with cane, the thing was unique — the Empire State Building of prehistoric America. (Its complex of stacked, geometric shapes makes a single term for it difficult, but the structure was clearly much more than a “mound”; recognizing the simplification, I’ll refer to it now and then as a pyramid.) It was a giant earthen exclamation point, a grand monument fitting to a grand river at its terminus.

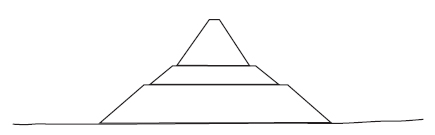

I fear my words will fail to show the pyramid precisely, so I’ll resort to a diagram I’ve taken from a theoretical one that Winslow Walker, the archaeologist who conducted the fullest investigation of the Great Mound, made in the early 1930s. The apex of what you see in the figure, all of it made of clay, rose to the height of an eight-storey building; when Dunbar visited, the pyramid was the tallest native structure in the South.

Diagrammatic reconstruction after Winslow Walker of the Great Mound as William Dunbar would have seen it in 1804.

Walker established the footprint of the structure, and then, combining Dunbar’s 1805 vertical measurements with his own horizontal ones, he was able to reveal through geometry the upper portion, the truncated cone, had to rise at a fifty-degree angle from its base atop the double terraces, or tiers, below. The angle of repose (angle of slide) for dry earth is thirty-nine degrees, but for damp clay, of which the mound was made, the angle can decrease to seventeen degrees; with that in mind, you might consider the engineering of the Great Mound in a rockless, fluent land as at least the equal to the stone pyramids in Egypt, Mexico, or Central America.

Referring to the edifice as a “mound” denigrates and did not help its survival. The tenacious soils of what the usually unimpassioned Hunter called a “stupendous turret” were packed down hard and perhaps locked in by buried cane mats. That peerless work stood for more than a thousand years in a climate notorious for hurricanes and for saturating downpours lasting all day. The pyramid would be there now for you to witness had a couple of decisions, otherwise of little significance, turned out differently. Although many archaeologically rich native mounds and middens around the country have been destroyed for simple road fill, nothing as splendid as the Great Mound has fallen for that mundane purpose.

Dunbar wrote that because the “ascent is extremely steep, it is necessary to support one’self by the canes which cover this mount, to be able to get to the top.” (The Indians may have used a narrow spiral ramp, perhaps one of timbers, but the answer to that mystery is now also lost.) Assuming hundreds of years of erosion must have reduced it, Dunbar thought the tower was originally even higher, although with the diameter of the crest only eight feet, the pyramid could not have held much more packed soil or had space at the top for a large structure.

The Ouachita River in southern Arkansas.

So what was the purpose of that extraordinary quoz at the heart of what may have been the “capital” of a region blessed with the conjoining of three rivers? Dunbar guessed a watchtower, but that function could have been more easily accomplished in a tall cypress. A signal station? A monument to a deity or person? A ceremonial pyramid? A giant gnomon for astronomical observations? Apparently, like most of the truly large Mississippian earthworks, it was not a mortuary, at least not initially. Then what was it?