Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (21 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

We watched the Ouachita until it began to disappear in the dusk, then Parish said, “Let me show you something else,” and led us off the deck and into a wooden cabin he’d saved from destruction and rebuilt as a guest cottage, turning the interior into a little gallery for his inventive opuscules: curtain rods made from tree branches, an American flag with stripes fashioned from old fence pickets and the union from a four-paned window with a half-dozen Gulf Coast starfish glued to the glass. He said, “Come back sometime and stay here.”

Parish was sixty-seven and retired from a local company that manufactured twine and rope products. He was smiling. “I used to have good connections.” He believed living along a river entailed responsibility, but his words for it were “Whatever we do here can keep on going downstream.” Seeing me pull out my little notebook to write that down, he added, “You put in how we take care of the end of the river.” Here was a man, were he a generation older and owner of the Great Mound, who might have made the history — the well-being — of Jonesville sweepingly different.

He went to the door. “Come on over to the house. I want you to see something in the garage, and you tell me if it’s not the only thing like it along the river.” Tuffy built his house in 1973 by incorporating where he could portions of an 1830s home originally on the site. Although the place was more than thirty feet above the usual river level, a couple of forty-foot rises had twice put water up to the windowsills. His wife, Ginger, a retired teacher of third graders, joined us in the garage while he went to a cooler to find four bottles of beer. I stood looking around for the curiosity he wanted us to spot.

When I was nine or ten and traveling the highways as my father’s navigator, I would imagine going up to selected front doors across the country and knocking and introducing myself and my assignment: a researcher with the Committee for American Curiosities whose task it was to discover all the peculiarly worthy things people squirrel away in their homes. I would show my credentials signed by Harry Truman and the Secretary of the Interior (interiors were our special domain), papers that would make a person eager to share treasures pulled from attic trunks, cartons at the backs of closets, even from a secret compartment in the chiffonier: the Mister’s cloth napkin Jackson Pollock spilled spaghetti red on, the Missus’s diary of Great-Grandmother Lavinia’s trip across the plains in 1848, Sister’s collection of roller-skate keys, Junior’s cigar box of subway tokens, Granny’s shelf of player-piano rolls. After full examination, I’d give the family a booklet of instructions on the best ways to pass along one day their troves to posterity. We would then all sit down at the kitchen table for a slice of apricot upside-down cake and a glass of apple cider. (You, astute reader, now see how so long ago this business of quests for quoz got started.)

While Tuffy opened the bottles and tried to match varieties to each of us, I looked around the garage for the something: surely it wasn’t the vehicles or basketballs or mower or the three pairs of rubber boots or the —

hold it.

What’s that thing on the wall above the Wellingtons? Something related to his picket-fence flag? Of similar size and shape, this one made of two planks, riddled with blackened nail punctures, two vertical smears of yellowed white paint, the right side with a jagged hole:

The Parishes watched me stare at it, and when I turned to them, their faces revealed I’d found the something. I said I knew I was seeing an oddity but I didn’t know what the oddity was. Tuffy said, “You mentioned an interest in river history, and that’s a piece of Ouachita history made out of cypress.”

I said I was going to need some help. He explained how in using components of the 1830s home to build his new one, he’d uncovered original planked walls, two exterior ones and two inside, all with a similar hole broken through them. The peculiarity was that the puncture in the front wall, the one facing the river, was much lower than the hole at the back; then he noticed all four breachings were in parallel walls and aligned at an ascending angle, with a base that had to be down on the water. Then he understood: the perforations marked the trajectory of a cannonball fired from river level, one likely from a Union gunboat during the Ouachita campaign. He found no other damage, so he cut out the planks around the four holes and turned them into hanging sculpture.

But why only one shot? “I think it was a warning, because a battery here did fire on the fleet,” he said. “Maybe somebody up here at the house took a potshot at them.” The cannonball reportedly ended up in a field a half mile away.

Parish passed a beer to each of us, a good thing since I’ve long believed calling-card cannonballs shot clean through a parlor a signal invitation to — if not a prayer — then at least a toast celebrating everyone who’s still alive to raise a glass. I said something along the lines of On behalf of Admiral Porter, may I tardily apologize for such an uncivil action against a domicile. And we drank to that. Then Q raised a second toast: “To that grand old Ouachita and all the wandering feet that reach her shores, long may she wave up!” And we drank to that too.

Into the Southeast

Into the Southeast

Doing What They Hadn’t Ort to Do

1. A Quoz of Conviviums

2. The Black Lagoon

3. Arrows That Flieth by Day

4. Dead Man Stream

5. Road to Nowhere

6. Bales of Square Mullet

7. A Taste of Manatee

8. Playground for the Rich and Famous

9. In There Own Sweat

10. The Truth About Bobbie Cheryl

Doing What They Hadn’t Ort to Do

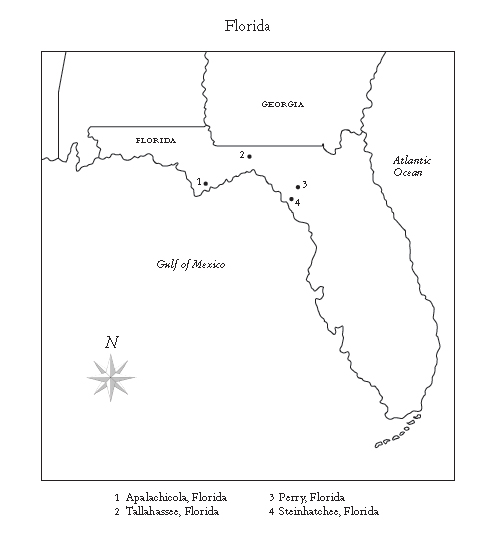

Steinhatchee has always been a close-knit community and isolated in as much as it is off the beaten path. The people are independent, resourceful, and filled with pride. All of this is a definite asset if one lives in an isolated, rough territory. But many others have taken advantage of this isolation to use it for hiding from the law or doing something they hadn’t ort to do.

Many old timers wish for better times and hope someday to be rid of the reputation that had spread far and wide. As the nation becomes over-populated, we need these off-the-beaten-path places to renew our lives and spirit from the rat race of daily living.

—Elsie Lee Adams,

Steinhatchee River Falls,

1991

A Quoz of Conviviums

T

HE NEXT LEG OF THE JOURNEY

began in 1969 in Columbia, Missouri, and the source of it was an utter concoction created by my close friend Motier DuQuince Davis. We were then undergoing the academic abuse attendant with getting a doctoral degree in English literature. As PhD candidates, we called ourselves Phuds. Mo and I were pushing thirty, married, and had served our required stints in the military — he in the Army (where he learned to do a parachute-landing fall, and with enough malted relaxant would demonstrate) and I on an aircraft carrier.

All that is to say we had experience enough to recognize professional hazing, even when disguised by tradition and open acceptance. Although the college was rich with teachers who gave meaning to the term

human studies,

we happened to fall into a cadre of inflated, neurotic, pluckless, costive-spirited literature professors who possessed a single skill: they could read artfully assembled words and spin out interpretations. If any youthful moisture of soul remained in them, it had turned to mildew. The range of their dry-hearted, withered passions ran only from annoyance to worry, with every petty stage between and nothing beyond. Genuine emotions were only topics in their lecture notes, where they could discourse safely on the rage of King Lear, the suicidal despair of Ophelia, the jollity of Falstaff. Yet it was those sciolists, those hollow Prufrocks never daring to wear their trousers rolled, who dictated our lives, and we dispiritedly acquiesced by assuming our eventual end at some quiet liberal-arts college would justify our acceptance of their means. We fools, as my friend called us, managed such delusion through spineless mutterings over mugs of cheap draft-beer.

Early one evening, several of us sat in a bar on Broadway in Columbia. Among us was an angular, sinewy student, younger than either Mo or I and innocent of military experience, full of repressed resentment and given to sudden and sometimes violent expressions of it, all of them prudently beyond the oversight of the professors. As the beer began to rile him, he said, “Tonight I’m going to find a fight or a fuck.” Mo, always of calm facade even if turbulent beneath, said, “Sonny, you got yourself there a pretty fair country-western song.” The kid shrugged. “Why not?” he said. “What are we but graduate-school rednecks? Who are we kidding?” He was working himself toward the fighting rather than the other. “What motivates us isn’t a professor. It isn’t even literature. It’s the

fantasy

of a future professorship. So here we sit in a college-boy bar when we ought to be swinging a pool cue at somebody in a Cracker tavern.”

Mo, who grew up in Macon, Georgia, said, “Bobbie Cheryl’s Anchor Inn. Outside Davidson, North Carolina. It’s an old roadhouse, falling down the hill into the creek. Men’s toilet’s got no door.” What was he talking about? “Above the bar there’s a ratty stuffed boar’s head wearing a Tar Heel necktie. The floor sags from two generations of dancing feet. There’s a fist hole in the wall above the urinal, but swinging a pool cue will get you tossed out. But you’re not going to find any doctoral candidates in there and no associate professors trying to snuggle up in a rickety hideaway with a coed their daughter’s age.”

How many words do we hear in our lifetime that are inconsequential flotsam immediately washed out of our lives to leave behind nothing, not even a residue? On the other hand, how many ordinary utterances — lacking apparent significance and free of indications they will survive beyond a moment or two — are there that seem to vanish, yet in some way resurface later, ready at last to shift a life? Bobbie Cheryl’s Anchor Inn — four words — did just that to me, but I had no awareness of its implications for a third of a century. I was blind, in nautical lingo, to Mo’s hook well-set in a hard bottom. I could recognize a metaphor on a printed page but not one in my life.

His précis of the Anchor Inn put me in it: I could see the red-neon anchor flickering in the window, and on a wall the name spelled out in a script of old ropes, and the back door held closed with barbed wire. I could hear pieces of conversations about deer hunting, women, government regulations, tractors, women, crankshafts, women, football, wives, death. I could imagine us there in front of Bobbie Cheryl herself: she in midlife, married three times and not again, missing a couple of incisors, chain-smoking, tattooed in a time when women had no tattoos, tolerating neither loud cussing nor putting your head down on the bar.

The Anchor Inn was, surely, a rendezvous of men — and a few women — wearing fertilizer and implement-company billed caps, who let fly with whatever might be going on beneath those hats, their sentences pungent and without pretense and rarely free of egregious solecisms. In the Anchor, a fellow like me would be tolerated and allowed to listen in as long as he kept his education to himself. A fair exchange.

Such a place had to be empty of vicarious life; it was an out-county dive, a crossroads tavern both in its topographical location and in its people gathered for conviviality. Despite the literariness of the High Professorhood running our lives, those men, several of them failed seminarians, would not deign to recognize the etymological relation between tavern and tabernacle. In their recently resecularized view, a trivial beer-joint could never be a house of Communion.

The ancient Romans, heathens to the new Christians, had a word for the Anchor Inn:

convivium,

a place of wine and song and conversations on matters requiring no decisions of consequence. Bobbie Cheryl’s, I was sure, was full of what our lives lacked because it wasn’t found on a written page; rather it was a place where we might find firsthand stories to put on a written page. It was the difference between secondary and primary sources.