Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (51 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

If the total population of the Starrucca Valley for the initial 150 years of the viaduct was — and I’m just guessing a number to make a point — ten thousand, then Young is the only one of ten thousand people who has had enough concern to dedicate himself toward preserving knowledge of the span, which, after the structure itself, is the most important aspect of its survival.

Years ago a civil suit was brought to tear down the Brooklyn Bridge as a navigational hazard on the East River. If such a beloved icon can be threatened, then what future perils await an isolated viaduct — never mind its beauty and historic significance? It’s possible one day, the sturdiest thing standing between those massive bluestone arches and a wrecker’s ball will be the forty pages of Young’s pamphlet. After all, America is not Italy where the great Claudian aqueduct has been allowed to remain for two-thousand years to inspire generations of engineers, architects, artists. For two millennia it has bridged not just the two sides of valleys but two sides of time, one of them the future. If William Young’s niche in American history is narrow, it also is deep.

No More Than a Couple of Skeletons

T

RAVELERS BOUND FOR RURAL NEW ENGLAND

can see they’ve arrived when villages fill with houses having front-door fanlights and Palladian windows, churches near a green are pedimented, porticoed, and pilastered, ferns grow just about anywhere untrodden by man or beast, and dry-laid rock walls enclose a burying ground having two or three slate markers attesting

MY GLASSE IS RUN.

Q and I made our way toward Mount Washington and the North Maine Woods via a hot-dog wagon in Connecticut, plates of clam fritters and steamers along Narragansett Bay, and bowls of chowder in Massachusetts. We passed through Franconia Notch where, until just four years earlier, the Old Man of the Mountain, that famed profile in rock, the Great Stone Face, kept watch over things.

After a night of heavy rain, it — he — broke loose and fell from the sheer cliff to get smithereened several hundred feet below. Up on the mountain, the yet-fresh scar — pink like a healing wound — was a sorrowful thing to see; the New Hampshire route markers, still depicting his silhouette, were continual reminders of mutability, even for men of stone. Said Q, “A regrettable loss of face.”

Never by any method — foot, horse, auto, rail — had she made the ascent of Mount Washington, the tallest peak in the Northeast, a six-thousand-foot-high rocky island of arctic plants and home to some of the worst weather on earth. Over the course of a year, the summit will average hurricane-velocity winds two out of three days, and at least once a month, they hit 150 miles an hour; one night it was 231. Beneath the crest, permafrost reaches down two-hundred feet to hold ice unthawed since before the last continental glaciation. Not many visitors, of course, make the trip up for violent winds and ancient ice — it’s the view or climb they want. When I was on the mountain a few years earlier, visibility was three feet, but under a rare clear sky, you can see the Atlantic seventy-five miles east. So I’ve heard.

Train buff that Q is, she was elated to take the antique cog railway to the summit. Few are the places in America where you can cover

exactly

the same route as travelers of 140 years earlier, and even fewer are those (at the moment I can’t think of another) where the conveyance is by the same vehicle, or one nearly so. Behind our coach, the little coal-fired, steam locomotive pushing us up was 135 years old, albeit replaced piece by piece over those years; perhaps somewhere in it was still an original brass knob or lever. After a few hundred yards of ascent, as I looked down the steep trestles that carry the entire track once it starts climbing, it was comforting to think not of antique bolts and gears but of replaced parts. Less reassuring was to see that the coach was unattached, except by gravity, to the engine, had only the locomotive and tiny tender between it and the bottom of the mountain.

Judging from the other passengers, one of whom refused to look back down the cogged tracks, the little pufferbelly was either “decrepit” or “cute,” the latter more commonly heard

after

we reached the summit about an hour later — a rise of 3,600 feet over three miles. The angle of climb in one place was nearly thirty-eight percent (in a hundred feet forward, you rise thirty-eight feet; only a cog line in the Swiss Alps was steeper, and merely by a degree or so). At that pitch, a seat at the front end of the small coach is fourteen feet higher than one at the rear, although the difference didn’t appear that great. The plump boiler sat tilted so that during ascent it was parallel to, say, the Atlantic Ocean but not to the mountain slope, thereby keeping water from draining off the steam tubes. One of the delights of passage was to notice how one’s brain began to adjust to the extreme incline by seeing the world beyond the tracks as horribly slanted: I was certain several spruces — in truth growing perfectly vertically — were leaning almost forty degrees toward Vermont. On a disturbingly canted maintenance shed — one appearing ready to slide down the mountain — was a sign:

THIS BUILDING IS LEVEL.

In the 1860s, the plan to get up to the top on slick steel-tracks got mockingly called the Railway to the Moon, in part because it was the first cogger in the world to try to climb the face of a mountain. Today, the ascent up the rails begins with great remonstrance from a smoky locomotive — seemingly of a size to fit a kiddie zoo. As the engine starts up, it whistles and spouts, sputters, shakes, shivers, shudders, knocks, and rattles in racketing, clanking, clanging, groaning, grinding, screeching, squealing, squeaking, spewing, hissing, smoke-belching protestations suggesting you have just boarded a train that can only transport you to singing hymns in the Angelic Choir. Although the little, green engine looked like something out of a child’s illustrated story, no one could possibly hear in its puff-puff-chug-chug,

I think I can, I think I can.

The noise was more the classic lament of seniority:

Oh, not again! Not Again!

After Q entrained, she said with some expectation, “This is better than a carnival ride. We’ll actually get somewhere. We’ll arrive in another place.” Jerkily, snortingly, blowing hot cinders, the locomotive began pushing us up. If years before I’d seen only as far as thirty-six inches will allow, the legendary Mount Washington weather fulfilling itself, for Q the sky opened, and from the summit — if we didn’t see quite to the Atlantic — we did see deeply enough to get an aerial sense of the White Mountains, sometimes called the White Hills. Below in the forest it had been almost too warm; but on top, the wind — no breeze, that gusting — required a jacket or a run for cover. Mount Washington rises near a nexus of three major storm paths, and their collisions often produce weathers so unendurable only a polar ice cap in winter can equal their vehemence. If the wind blows at two-hundred miles an hour and the temperature is twenty below, what’s the windchill? Lethal.

When the time came to go back down, I looked down the winding cogs (I mean to give some emphasis to the

down

s in that sentence). I’d read about a method used by nineteenth-century trackmen to return to Base Station faster than ambulation allowed. Sitting on a narrow three-foot-long board straddling the cogs centered between the rails, relying on the crudest of friction brakes, workers could toboggan toward home on what they called a Devil’s Shingle. One fellow reached the station, a descent an engine requires about an hour to make, in two minutes and forty-five seconds. Not everyone did it quite so fast, and not everyone did it without injury, and Devil’s Shingles were outlawed in 1906.

But what I found most remarkable about the cog railway had to do not with speed but with distance: even in living memory, a traveler could once board a coach in beachy San Diego (to pick a place) and just by changing trains disembark two days and more than three thousand miles later into the arctic world atop Mount Washington.

The portion of the northern Appalachians called the White Mountains, square mile for square mile, may have the most extensive shelf of relevant books of any range in America, a literature beginning in the late eighteenth century. The nearest comparable topography around is the Green Mountains in Vermont, but for every word they have evoked over the years, the New Hampshire range can show, so I’d guess, five times that. It’s as if some travelers come into the country through one of the three great notches and thereupon get imbued with an urge to describe the territory, to tell

its

tales or tell

their

tales about it. Were the White Mountains in the South, that land of natural tale-tellers, the stories might fill American literature and leave little room for the rest of us. And perhaps a reverse is true: were the range in Minnesota, we would not yet have heard about them.

Beyond beauty and their proximity to a populace of generally well-educated citizens — Harvard Yard is only 120 miles away — the bookish attention to the White Hills is much the result of a national forest established there in 1918, a protection that helped keep out early-day rapacious, liquidating, timber operations to create a future of tourists, hikers, climbers, hunters, skiers, and artists who replenish themselves somewhat faster and spend more on lattes than a stand of spruce. That wisdom of long-lasting prosperity for the many over short-term profit for the few set up my expectations for the North Maine Woods lying, geologically at least, not far from the tail end of the New Hampshire range.

We left the mountainous forest and followed broken hills northeast to Skowhegan, Maine, where one cool and gloomy morning we came upon the Empire Grill. We were drawn to it not so much by the old red-neon Indian glowing in profile as by two simpler signs also suggesting another era:

HOT MEALS. BOOTH SERVICE.

Inside was that unmistakable and memory-releasing scent unique to an American breakfast café: vaporing coffee, toasting bread, hot maple syrup, a wisp of eggs-over-easy. On a morning of thorough Maine dismals, I suddenly had reason — beyond eventual necessity — to have gotten out of bed. I heard, as if an addendum to my remark: “A reason to get out of bed? How about why you’re alive? When is it you don’t hear the Empire Grills of America calling?”

Before going again to the road, we walked worn Water Street with its shop windows of dusty merchandise. In one hung a sign:

WE GOT ’EM! BUG SUITS!

(Q: “Roaches dressed fit to kill?”) If you’ve ever put yourself near trees or water in northern Maine in early summer, you know the reference is not to bug toggery but to a collection of winged things, from the invisible (midges) to the whining (mosquitoes) to the silent (blackflies) and on down to crawlers (ticks). Some people refer to the North Maine Woods as “uninhabited,” but an estival stroll anywhere near water or timber will disabuse anybody of that description, for the place is fully inhabited, and the habitants are nature’s first line of defense against the sprawling of humanity into one of the last great, forested realms in the Northeast. To be sure, Americans owe a debt to the blackfly, for without it we might have Six Flags Over Moose World and its attendant parking lots, tract housing — well, you know the story.

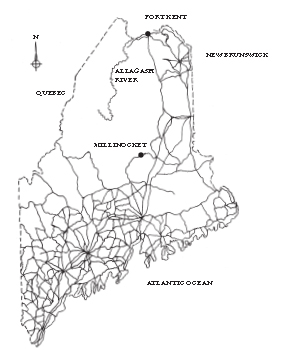

As we rolled on northward, the territory thinned of humanity and its contemporary disfigurements. At the old mill towns of Millinocket and East Millinocket, the highways at last shied away from the northwest corner, the so-called Unorganized Territory, the North Maine Woods still largely owned by timber companies feeding paper mills, although ownership was changing (about that I’ll say more shortly). From Route 11 on the east and south, the Woods lay unintruded upon except by privately owned logging roads and some fish and hunting camps. With the exception of Baxter State Park, for a hundred miles west and more than that north, there was no entry without permission of the corporations calling themselves the North Maine Woods, Inc., as though they were the forest itself. (I’ll use that term to refer to trees, not companies.) In area, imagine New Hampshire without pavement and population. An expanse that size in the Far West would draw scarce attention to private enterprises controlling open access to it, but in New England, a million square-miles is a significant piece of realty to lie beyond unrestricted public purview.