Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (54 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

After she brought our supper, she asked what we were doing so far from home, and I explained how we’d taken the entire longest day of the year to drive the hundred-and-some miles from Millinocket up through the Allagash to arrive at her table. “Why would you do that?” she said, then, catching herself, “Oh, by accident — you got lost.” Q said, “That’s half right.”

The next morning when I was transcribing notes from my memoranda pad into my logbook, I came upon a notation I’d made in Maine two days earlier when I saw a sign in front of a house where dilapidation was about to yield to collapse:

GOD STILL PLANS TO MAKE FARMINGTON HIS NEW J£RUSALEM.

Reading my note, I realized I’d been remiss in not stopping to talk with someone who knew the mind of God. I might have learned whether the Divine Plans include a review of the original purpose of the North Maine Woods. If not, it looked like it would be up to us. I think that’s what Raven whispered.

Into the Northwest

Into the Northwest

“May No One Say to Your Shame

All Was Beauty Here Till You Came”

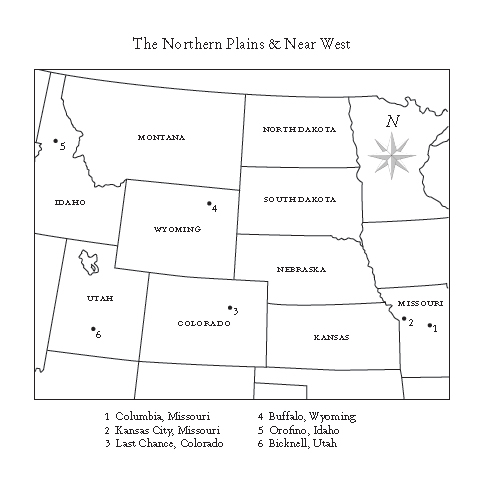

1. Out There Beyond Last Chance

2. The Widow’s Man

3. How Max Oiled the Hinges

4. Querencia

5. What the Chatternag Quarked

6. A Smart Bike

7. Railroad on Stilts

8. Printer’s Pie

“May No One Say to Your Shame

All Was Beauty Here Till You Came”

Beautiful as the transparent thin air shows all distant objects, we have never found the great western prairies equal to the flowery descriptions of travelers. They lack the pure streamlet wherein the hunter may assuage his thirst, the delicious copses of dark, leafy trees; and even the thousands of fragrant flowers, which they are poetically described as possessing, are generally of the smaller varieties; and the Indian who roams over them is far from the ideal being — all grace, strength, and nobleness in his savage freedom — that we from these descriptions conceive him. Reader, do not expect to find any of the vast prairies that border the upper Missouri or the Yellowstone rivers, and extend to the Salt Lakes amid the Californian range of the Rocky Mountains, versant pastures ready for flocks and herds, and full of the soft perfume of the violet. No; you will find an immense waste of stony, gravelly, barren soil stretched before you; you will be tormented with thirst, half-eaten up by stinging flies, and lucky will you be if at night you find wood and water enough to supply your fire and make your cup of coffee; and should you meet a band of Indians, you will find them wrapped in old buffalo robes, their bodies filthy and covered with vermin, and by stealing or begging they will obtain from you perhaps more than you can spare from your scanty store of necessaries; and armed with bows and arrows or firearms, they are not unfrequently ready to murder, or at least rob you of all your personal property, including your ammunition, gun, and butcher knife!

—John James Audubon & the Reverend John Bachman,

The Quadrupeds of North America,

1854

Only to the white man was nature a wilderness and only to him was the land infested with wild animals and savage people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessing of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families that we loved was it wild for us. When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was for us the Wild West began.

—Ota K’te (Luther Standing Bear),

Land of the Spotted Eagle,

1933

Out There Beyond Last Chance

A

S A PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGION,

the Great Plains are — by an archaic description — a land of little topographical relief; but for me, as a topography of the mind, they are forever a place of considerable relief. Entering from the east, I come into them relieved of ever-increasing human congestion, and entering from the west, I reach them pleased to leave behind horizons congested by mountain roads impeded with twisted curves. When I see the grand openness lying immensely ahead, my response is: And now for some

plain

sailing! Crossing the Plains is like reading a nineteenth-century Russian novel: you begin hopefully only to reach the end (if you do) muttering weak huzzahs and vowing once is enough.

So, as always, I looked forward to the Great Plains when Q and I set out a few days before the arrival of autumn. We made a stop in Kansas City to attend the fiftieth reunion of my class of ’57, one event held at Southeast High School where I’d not set foot for half-a-century. It was happenstance during my teenage years that Gus Kubitzki lived only a couple of blocks away and directly in line with the front doors of the school. Having heard on our excursions enough about Gus to feel she had met him somewhere along the way, Q wanted to see his hand-built bungalow in order to have a sense of the man beyond my stories of him. I have waited until this moment to tell you, road-worthy reader, a few facts about him so that he might first emerge in your imagination fleshed out with your colorations. All I want to do now is top those off, perhaps expand and refine them a smidgen for you and let you see that he is not an anonym.

Gus Kubitzki in 195.

To clarify any misperception of his Slavic surname, he described himself — unequivocally — as of Prussian descent. Although born in Ohio, he often tossed at me simple old-world phrases, a bold thing in the ’40s, when the Third Reich was still fresh enough in all our minds for German words to send a chill. He was tall for his time, broad-shouldered, with strong arms and large hands. In the early years of the twentieth century, he was a pitcher for a semiprofessional baseball team in Cleveland, if I remember correctly. When he was born, home plate was not a pentagon but a simple square, a batter got four strikes, a base on balls counted as a hit, and catchers wore no shin guards.

As we would toss a baseball back and forth, Gus often told me about games he played years earlier, about crazy plays, lucky bounces, a “home run” he hit no farther than three feet but that the catcher pounced on and threw into a cabbage patch beyond right field. Especially, he talked about striking out a pitcher named George who swung a good stick: “He never got the bat off his shoulder on the first strike. Strike two was a big curve the catcher couldn’t even handle. And, on the third pitch, down he went on a slow ball right over the plate.” I knew each throw, and I’d mouth the result along with Gus, but I wasn’t smart enough to pick up why he kept retelling the story, especially since the kid, a pitcher, was eight years younger. But after a while I began to suspect there was something behind the repetitions, a detail I was supposed to discover. One day he called the player Herman, and I said I thought his name was George. “George Herman,” Gus said.

On a warm August afternoon in 1948, as he threw me a few dawdling curves, his Sunday cigar in a holder clenched between his teeth, he once again told the strikeout story but concluded it this time with “Herman died yesterday. It made the front page.”

Yeah, yeah,

I thought. That evening I pulled a

Kansas City Times

from the box where we kept them for the annual Boy Scout newspaper drive. On the front page was a small headline, something like:

BABE RUTH DIES.

Great Scott! I’d been catching curves from an arm that once whiffed George Herman Ruth.

Perhaps because of that feat — or maybe because Gus’s name was also William — he was the only person other than an aged Sunday-school teacher I allowed to call me Billy. And why not? Here was a Nestor who could pop a boy’s catcher’s mitt.

Once again, abiding reader, I’ve let my story tumble forward too fast, eager as I am to tell it to you.

A few years after the death of my maternal grandfather — a man who tossed out not curves but tales of the Spanish-American War — Gus, a widower, wedded my grandmother, a marriage we all honored. My mother and her sisters loved him, although he had a habit, said one aunt, that came straight from Satan: at the supper table, during our standard-to-the-point-dozen-word-plus-

Amen

grace, Gus did not bow his head. He looked directly forward as if staring something down. At age eight I loved that moment because I was sure heavenly remonstrance sooner or later would happen right there over the Sunday chicken and dumplings — probably nothing dramatic like his forehead suddenly sprouting horns, but maybe a warning shot, like his pupils turning into vertical slits. Such flagrance in the face of Powers Eternal,

that

just had to be asking for it. Then again, a man who could whiff the Babe might also be able to slip a fast one past a deity or two.

The way things turned out, nothing at all occurred, and Gus’s years exceeded those of all but one of my blood ancestors; what’s more, as he of generous heart aged, I saw the grip of the Devil loosen in my brain until I no longer believed there was a Devil to grip anybody’s brain. So you see, had young William Kubitzki not one afternoon fanned the Bambino, my theological notions might today have quite a different cast, and this book might be a tract about sin and redemption. But then again, maybe it is.

I tell these few things about Gus because Q once said I traveled as if he were in the backseat. I don’t believe his revenant ever was, but he indeed has done many miles in the back of my head, including more than I can account for in crossing the Great Plains by each of its major auto routes, a number of those passages made solo, a condition almost necessitating voices in the back of one’s head. It’s good for sanity to traverse the Plains with a companion (even if your own memory) who can tell stories. Should you have ever crossed with children (in the days before electronic distractions), you may remember the value of a tale, no matter where it ranged on the whopper index: my father once got me through two Kansas counties (and into a hell of a nightmare) with one about a boy forced by Old Man Grimsley to bury Mrs. Grimsley’s severed arm which for months afterward would drag itself from the grave each Wednesday night to hunt for the soft throat of the boy who could chokingly tell the appendage where the rest of the body was. A shrewd parent knows monotony is not a physiographic fact but a mental condition, something the Great Plains teach, as does the open sea.

On one eastward crossing, I stopped near the western edge in Last Chance, Colorado. At the café counter was a woman heading to her home along the Front Range. When I asked how the town got its name, she said, “It used to be the last chance to fill your tank or get a soda pop, but the real reason if you ask me is that it’s your last chance to turn back before you get way the devil

out there.

” With the last two words, she waved her arm eastward all the way to Missouri. I said I liked it

out there.

“So do I,” she clarified. “It always reminds me how much I love trees.” Here was a woman who might like a bald man just for making her thankful for a hairy husband. Her point, nevertheless, stands: who can doubt deprivation being a keen intensifier of appreciation?

The Great Plains seem destined to be misperceived and consequently misunderstood by any traveler arriving with assumptions and myths rather than with eyes and mind open. If we’ve at last gotten beyond the early description — the Great American Desert — we’ve still not entirely escaped a frequent conflation of two homonyms:

plain

and

plane.

The expectation of finding a realm of two dimensions (which at times can even look like a place of one dimension — that of

across

) is likely to fulfill itself, because the third dimension of height often seems measurable only with a micrometer.

In truth, no matter how difficult we find them to perceive, there are assuredly three dimensions

out there.

I would even argue there is also a fourth: rare is the traveler who can cross without occasionally tapping a watch to see if it’s stopped.

The other homonym,

plain,

is also misleading, tinged as its dozen or so meanings are with inaccuracy and negativity: (1) unobstructed; (2) uncomplicated; (3) unmixed; (4) undecorated; (5) unpretentious; (6) neither beautiful nor ugly; (7) not hard to comprehend; (8) not unusual. Only the first term has a tincture of accuracy, and I think it’s the meaning white Americans had in mind when they first encountered the vastness some two centuries ago. On a clear day — even in the pollution-dimmed skies of our time — if you are on a rise (like the back of a pickup), you may be able to see forty miles around. Were you on a horse or behind a team of oxen heading westward in 1848, you could see all the way into your next week.