Roberto & Me (2 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

A Mission of Mercy

AS I PEDALED MY BIKE HOME, I MANAGED TO GET MY MIND

off the game by thinking about my birthday. It was coming up, and I decided to ask for a portable video game system. I have a secondhand Game Boy that is like a thousand years old. But I saw in a magazine that Nintendo has a new system coming out that is very cool.

I hopped my bike over the edge of the driveway and wheeled it into the garage. In the kitchen, my mom was preparing dinner, still in her nurse's uniform. She works in the emergency room at Louisville Hospital. Usually she works the night shift, but today she was home early.

“Hey, Mom, I was thinking,” I started, “for my birthdayâ”

I probably should have checked her mood before launching into the conversation.

“Mister, you're in trouble,” she told me.

She didn't have to tell me I was in trouble. I knew I was in trouble because the only time my mother ever calls me “mister” is when I'm in trouble.

She handed me a piece of paper that said

PROGRESS REPORT

at the top. In between report cards, my school sends out progress reports to parents to let them know if their kid is screwing up or not. I don't know why they call it a progress report if they basically say you're not making much progress.

The progress report said that I was doing fine in all my classes except Spanish. There was a note that said

POOR WORK

and some code after that.

“I thought I was doing okay in Spanish,” I said.

“If flunking is okay,” my mom said, “you were right. It says that if you don't do something to bring up your grade, Joey, you're going to get an F on your next report card.”

I'm a pretty decent student. Let me say that right now. But I would be the first to admit that I'm not very good in Spanish. I just don't get it. I don't see why I have to learn a foreign language, anyway.

At my school, we have to take Spanish, German, French, and Italian, each for one marking period. Then, at the end of the term, we choose one language to study the following year. I'm definitely

not

going to choose Spanish.

Â

The next day, like it or not, I had to go talk to my teacher, Señorita Molina, to see what I could do to

bring up my grade. I have Spanish last period on Thursdays, so I just waited until the other kids left the class before approaching Señorita Molina.

She's an okay lady, I guess. Kids think she's kind of strange. Like, she keeps a lit candle on her desk at all times, but she never tells anybody why.

Señorita Molina can't walk. She's in a wheelchair, and the whiteboard in her classroom is lower than normal so she can write on it from a sitting position. There have been lots of times in the lunchroom when me and some other kids sit around and try to guess what happened to Señorita Molina to make her disabled. But nobody knows for sure. And nobody has the nerve to ask her. She's one of those teachers who gives you the impression she doesn't want to talk about personal stuff.

“

Buenos dias, Tito

,” she said when I came over to her desk.

Tito is my Spanish name. On the first day of school, Señorita Molina said that each of us had to choose a Spanish name for ourselves. Most of the names sounded lame, but Tito sounded kind of cool, so I chose it.

“My mom got the progress report in the mail,” I said.

“I was disappointed, Tito,” said Señorita Molina.

“I'll try harder,” I told her.

“Tell you what,” she said. “You can do an extra credit project to bring up that grade.”

“What sort of extra credit project?” I asked.

“Whatever you like,” she said. “

Usa tu imaginación, Tito

. Use your imagination.”

She looked down at her papers, so I figured she was finished with me. I was about to leave; but then I figured, what the heck? Nobody else was around. It was just the two of us. What did I have to lose?

“Señorita Molina,” I said, “why do you keep a candle burning on your desk?”

She looked up at me, not with anger in her eyes but with sorrow. She paused for a moment, as if she wasn't sure she wanted to confide in me or not.

“It is for Roberto Clemente,” she finally said.

Well, being a big baseball fan, I knew a thing or two about Roberto Clemente. Just about the only thing I ever read is baseball books. I've got a whole shelf of them at home. I know a lot about baseball history, both from reading and from seeing it with my own eyes.

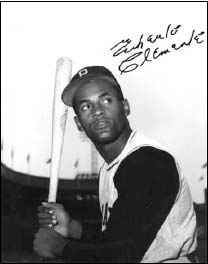

I knew that Roberto Clemente played for the Pittsburgh Pirates, mostly in the 1960s. Rightfield. He had a great arm, and he was one of the few players to reach 3,000 hits. No more, no less. 3,000 hits exactly. He's in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Señorita Molina reached into her drawer and pulled out a framed picture.

“I met Mr. Clemente when I was

una niñita

, a very little girl,” she told me. “I grew up in Puerto Rico, and so did he.”

“How did you meet him?” I asked.

“I was so young, I barely remember,” Señorita

Molina said. “It was toward the end of 1972. I developed an infection in my spine and had to spend the whole year at San Jorge Children's Hospital. That's in San Juan. There was a

medica mentos

âan antibioticâthat could have made the infection go away, but my family was very poor and could not afford a hundred dollars to pay for it.”

It was a photo of Roberto Clemente. He had even signed it.

“Is that why you have the wheelchair?” I asked.

“

SÃ

. Yes. Anyway, Mr. Clemente visited the hospital one day. He would do that all the time. There were no photographers or reporters there. He just did it because he cared. And he was so nice. The big baseball starâsitting at the edge of my bed! He told

my parents that he was going to come back in a few weeks and give me a hundred-dollar bill so I could get the antibiotic I needed to get better. But he never did.”

At that point, I could see Señorita Molina's eyes were wet. It occurred to me that maybe I never should have asked her about the candle.

“Why do you think he didn't come back?” I asked.

“Because

se murio

. He died, Tito.”

Señorita Molina dabbed her eyes with a tissue and told me what happened. On December 23, 1972, there was a huge earthquake in Nicaragua, which is in Central America. It just about leveled the capital city, Managua. 350 square blocks were flattened. Two hospitals were destroyed. The main fire station collapsed. 5,000 people died, and 250,000 were left homeless, with no water or electricity.

Señorita Molina told me that Roberto Clemente had played winter baseball in Nicaragua and grew to love the people there. He wanted to help. So he organized a relief effort in Puerto Rico to get food, medicine, and clothing for the survivors of the earthquake. And he personally paid for a plane to fly the supplies to Nicaragua. He even insisted on going on the plane himself to make sure the stuff got to the people who needed it.

At that point, Señorita Molina cried as she pulled a yellowed newspaper clipping out of her desk drawer and showed it to me.

“It was

La Noche Vieja

âNew Year's Eve,” Señorita Molina told me. “The plane was loaded with 40,000 pounds of cargo, more than it was supposed to carry. The pilot was sleep deprived and in danger of losing his license. The crew was unqualified. There were mechanical problems too. The plane was only

volano

â¦how do you sayâ¦airborne for two minutes before it crashed into the ocean. Five people died, including Mr. Clemente.”

“I'm sorry,” I told her. I didn't know what else to say.

“

La Noche Vieja

is one of the biggest nights of the year in Puerto Rico,” she told me. “Mr. Clemente left his wife and three young sons that night to help the earthquake victims. He was not looking for publicity or fame. It was a mission of mercy. In Spanishâas you should know, Titoâthe word â

clemente

' means âmerciful.'”

I felt like it was time for me to go. I thanked Señorita Molina for giving me the chance to bring up my grade.

But after I left the classroom, I stopped dead in my tracks in the hallway. An idea popped into my head.

I could stop it!

I could go back in time and make sure Roberto Clemente didn't get on that plane.

I could save his life.

Just Do It

I GUESS I NEED TO DO A LITTLE EXPLAINING. ONE DAY, WHEN

I was a little kid, maybe eight or nine years old, I picked up one of my dad's baseball cards. He used to have a huge collection, and his cards were all over the house. It drove my mom crazy. In fact, that was one of the reasons they got divorced.

Anyway, I picked up this card that was on the table. It was an old card. I don't even remember who was on it. I was staring at this card, and, suddenly, I felt this strange tingling sensation in my fingertips. It was unlike anything I had ever experienced before. And as I continued to hold the card, the tingling sensation became stronger and moved up my arm. It was almost like bugs crawling over me.

I kind of freaked out, you know? So I dropped the card, and the tingling sensation stopped right away.

But I was intrigued. I started experimenting with

other baseball cards. Each time, I was a little less fearful and held on to the card for a few seconds longer.

Finally, one day I was lucky enough to stumble on a Honus Wagner T-206âthe most valuable baseball card in the worldâand I decided not to drop it. I didn't let go of the card. The tingling sensation moved up my arm, across my body, and down my legs, getting more and more powerful until I felt like I was vibrating from head to toe. It wasn't an unpleasant feeling. Actually, it felt kind of good.

And then, suddenly, I felt myself disappearing. It was almost as if every molecule that made up my body was being digitally deleted and emailed wirelessly to another location. Very strange.

When I opened my eyes, I wasn't in my house in Louisville, Kentucky, anymore. I was in the year 1909â¦with Honus Wagner.

But that's a story for another day.

The point is, I discovered that I have the unique ability to travel through time with the help of a baseball card. For me, a card is like a plane ticket. It takes me to the year on the card.

Since that day, I've been on a number of trips through time. I got to meet Jackie Robinson, Babe Ruth, Satchel Paige, and a bunch of other famous players. I always bring a pack of new cards with me, because that's my ticket home, back to

my

time.

Maybe I was being a little overambitious, thinking I could travel back in time, change history, and

save Roberto Clemente's life. I mean, I had tried to change history before. My coach, Flip, once told me about this guy named Ray Chapman, who played for the Cleveland Indians. He was the only guy in major-league history to die from getting hit by a pitched ball. I'd figured I would go back to 1920 and save Chapman's life. It should have been simple. But I messed up, and it didn't work. Other times I'd tried to save the reputations of Shoeless Joe Jackson and Jim Thorpe. That didn't work either. I'd even tried to prevent the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. That was a disaster.

Come to think of it, I don't think I have

ever

been successful with any of my missions. I wasn't even able to see if Babe Ruth really called his famous “called shot” home run or see how fast Satchel Paige could throw a fastball.

But those are stories for another day too. The thing is, I've got this power, this gift. Nobody else in the world has it, as far as I know.

If you could do something that nobody else in the world could do, you would want to do it, right? What a waste it would be to have a special power like that and not use it. I had to at least

try

to save Roberto Clemente's life.

How hard could it be to prevent a guy from getting on a plane that's doomed to crash? Probably not as hard as it would be to convince my mom to let me go.

You see, time travel is

dangerous

stuff. It has

been for me, anyway. The time I went back to 1919 to help Shoeless Joe Jackson, a bunch of gangsters kidnapped me, tied me to a chair, and almost shot me. Another time, I took my mother back to 1863 with me, and we landed in the middle of the Battle of Gettysburg, with bullets whizzing by our heads.

That

was interesting. So I have to be careful about bringing up new time travel trips to my mother.

I finished my homework and went downstairs. Mom was at the kitchen table, paying bills and doing some paperwork. There was music coming from the radio she keeps next to the sink.

“What is that horrible sound?” I asked.

I make fun of my mother because she listens to this awful oldies music from the sixties. The “classics,” she calls them.

“That's Jimi Hendrix,” Mom said. “âPurple Haze'!”

“Ugh, how can you listen to that?” I said, covering my ears. “It's not music! It's just noise.”

My mom laughed, because my grandparents used to say the same thing to her when she was a little girl.

“Hendrix was a genius,” my mother told me for the hundredth time. “And like a lot of geniuses, he died young. He died of a drug overdose in 1970, when he was just 27. Such a tragedy.”

She gave me the perfect opening.

“Mom,” I said, choosing my words carefully, “speaking of people who died young, does the name

Roberto Clemente mean anything to you?”

My mother knew that Clemente was a ballplayer, but that was about it. She's not a huge baseball fan. I told her a little bit about Clemente and how he died in a plane crash while trying to deliver medicine and supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua.

“That's so sad,” she said.

“Mom, I was thinking,” I said, “maybe I can do something about it. I don't have to get on the plane or anything. All I have to do is find Roberto and make sure

he

doesn't get on the plane. If I can do that, he won't die. I'll be real careful. And it will be educational. It will be⦔

I figured I would be in for a tough battle. My mother is a little on the overprotective side. You knowâI'm an only child and she's a single parent and all. If anything ever happened to me, she would be all alone.

But she surprised me. It took her about a millisecond to make up her mind.

“Do it,” she said simply.

“Really?”

“

Do

it,” she repeated. “Joey, do you know why I became a nurse?”

“Because you're into blood and gore and guts?” I guessed.

“No, to help people,” she said. “I could have chosen a career that paid more money or would have been fewer hours. Less blood and gore and guts. But I wanted to do something good for the world. I hope

that when you grow up, you'll use the skills you have to help other people in some way. You should have a cause. Everyone should. So, by all means, I approve. Go save Roberto Clemente. Just be careful.”

I thought about what my mother said. I confess, when I first started traveling through time, all I really wanted to do was meet famous baseball players. It was just a joyride. But when I saw how dangerous it was, I decided to do it only if I had a real mission to accomplish. I wasn't about to risk my life just to see some guy hit a famous home run. That's what video is for. And now I had come around to thinking I would only travel through time if I could do some good, right some wrong, help somebody. And if I could save Roberto Clemente's lifeâwell, the world would be a better place. Because if he had 40 or 50 more years to help people, he could have accomplished so much more.

“Do you want to come with me?” I asked my mom.

“It's tempting,” she said, “but going back in time once was enough for me.”

Now for the next part of my mission, which should be the easy part: All I had to do was get a Roberto Clemente baseball card.