Roberto & Me (5 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

Sunrise

I DON'T KNOW HOW LONG I WAS OUT. PROBABLY ONLY A FEW

minutes. When I came to, I staggered away, thankful those peaceniks hadn't killed me. What had I been thinking? Trying to save Jimi Hendrix from himself was probably the stupidest idea I ever came up with.

Suddenly, a guy with stringy blond hair walked over to me and stuck his face in front of mine.

“Hey, man,” he said, “if life is a grapefruit, then what's a cantaloupe?”

“How should I know?” I said, pushing the guy away.

I cleared my head. I had to get back to the reason why I came here in the first place. Roberto Clemente. He wasn't at Woodstock. He wasn't anywhere

near

Woodstock. Something had gone terribly wrong. Something

always

goes wrong. Time travel is simply not an exact science.

Think

, I told myself. It was hot out. It was baseball season. Roberto Clemente had to be playing ball somewhere. The question was, where?

The only thing I could do was follow the hippies as they started to pack up their stuff and make their way toward the exits. The field was a huge mess. There was mud and garbage everywhere. It must have rained a lot during the festival. People left behind tons of soggy clothes and blankets.

Some people were in no rush to leave. They were hanging around, sleeping, doing yoga exercises, or tending campfires made of burning garbage. A few were running around with no clothes on. It looked like one of those movies where an atomic bomb went off and a small group of human survivors were left to live off the land.

I spotted a newspaper on the ground, and I picked it up.

Okay, I knew

when

it was. Obviously, it was too late to help the Yankees win the 1960 World Series. My dad would have to deal with that. But it wasn't too late to help Roberto Clemente. He would be alive until December 31, 1972.

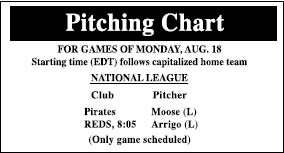

I flipped through the paper until I found the sports section.

Okay. The Pittsburgh Pirates were playing the Cincinnati Reds tonight. At 8:05. The Reds were the home team. So Roberto Clemente must be in Cincinnati.

That's where I had to go.

Â

Getting a huge crowd of people out of a large field at the same time isn't easy. Some of the hippies had cars; but they weren't going anywhere, because the road was one huge traffic jam. Other people had bikes, motorcycles, or roller skates. Many were on foot.

Lots of kids were looking to catch a ride with somebody else who was heading in the same direction. People were holding up hand-lettered signs:

NEW YORK CITY

.

FLORIDA

.

CHICAGO

. And so on. One guy held up a sign that simply read

ANYWHERE USA

.

Then I spotted a small sign that said

CINCY

on it.

It was held by a pretty girl in a flowered dress. She had long, straight brown hair; a white headband; and a string of beads around her neck. She

didn't look much older than me. I wondered why her parents would let her come all the way to New York by herself.

“Do you live in Cincinnati?” I asked her.

“Yeah,” she replied. “You?”

“No, but I need to get there tonight.”

“What's the rush?” she asked me.

“It's a long story,” I told her. I didn't feel like going into all the details unless I really had to.

“What's your name?” she asked.

“Joe Stoshack,” I said. “But you can call me Stosh. Everybody does.”

“You look kinda straight, Stosh,” she said.

“Straight?” I said. “Would it be better if I was crooked?”

She laughed, and then I realized what she meant. I didn't look like a hippie. I didn't have bell bottoms, flowers, love beads, or any of that other hippie gear.

“I guess I am,” I admitted.

“That's cool,” she said. “You're doing your own thing. Different strokes for different folks. My name is Sunrise.”

Sunrise?

I'd never heard of anybody named Sunrise.

“Is that your real name?” I asked.

“No,” she said, giggling.

“What's your real name?”

“I hate my name!” she said.

“It must be pretty horrible,” I said, “What is it, Barbara Hitler or something?”

She giggled again. She had a nice smile.

“It's Sarah Simpson,” she said.

“Ugh! Disgusting!” I said. “No wonder you changed it. How could anybody go through life with a name like Sarah Simpson?”

She knew I was teasing her, and she hit me playfully with her

CINCY

sign.

“I like Sunrise better,” she said. “It means a new day, y'know? Whatever mistakes you made yesterday are forgotten. You get to start all over again. That's what I'm trying to do.”

“Well, I think Sarah Simpson is a perfectly nice name,” I told her. “But I'll call you Sunrise if you want.”

She giggled again and took my hand.

Let me admit something right now. I've never had a girlfriend. I've never been out on a date with a girl. I've certainly never kissed a girl. Usually, in school, when I have to talk to a girl, I'm totally tongue-tied and make an idiot of myself. But I felt completely comfortable with this girl. I had known Sarah “Sunrise” Simpson for about 30 seconds, and I was already in love. She told me she was 14, and it didn't seem to bother her that I was a year younger.

“Cincinnati!” we yelled as we walked past a long line of cars heading for the main road. “Anybody going to Cincinnati?”

Sunrise and I walked about a mile down the road. We were looking for Ohio license plates. There were cars from just about every

other

state, even Alaska. I

didn't mind it so much though, because Sunrise was holding my hand.

We came upon a Volkswagen van with California plates. It had peace signs and flowers painted all over it. A hippie guy and girl were tying some stuff on to the roof of the van. I was going to pass them by, but Sunrise asked them if they were driving cross-country.

“San Francisco,” the guy replied. “We gotta get there by Friday.”

“Could you drop us off in Cincinnati?” Sunrise asked. “It's on the way.”

The guy and his girlfriend stopped what they were doing and looked me up and down. I made a halfhearted peace sign with my fingers, hoping that might help me pass the hippie test.

“What are you, the fuzz?” the girl asked.

“Huh?” I said.

“Are you a cop?” asked the guy.

“A

cop

?” I said, laughing. “I'm 13 years old!”

“Then what are you doing here, man?” he asked.

“You wouldn't believe me if I told you,” I said.

“Try us,” they both replied.

I looked at Sunrise, and she nodded encouragingly.

When in doubt, tell the truth. That's what Coach Valentini says.

“Okay, here goes,” I told them, taking a deep breath. “The truth is, I live in the twenty-first century. I can travel through time with baseball cards,

and I used a 1969 card to get here.”

The three of them stared at me for a long time.

“So, in other words,” the guy said, “you're saying you, like, come from the future?”

“That's right.”

“Stosh, are you putting us on?” said Sunrise.

“No,” I told her. “I'm telling you the absolute truth. I swear on my mother's grave.”

They all looked at me some more, like they didn't exactly know what to make of me. Then, finally, all three of them said, “Far-out!” They probably thought I was kidding.

“No, I mean it!” I said. “I really

am

from the future.”

“Groovy,” the girl said. “I can dig that.”

“We're

all

from the future,” said her boyfriend. “The future of our soul.”

“Here, I'll prove it to you,” I said as I swung my backpack off my shoulder and pulled open the zipper. “I bet you've never seen one of

these

before.”

I took out my Nintendo. They gathered around me to look over my shoulder as I turned it on. It must have looked like a little TV to them.

“You can control what's happening on the screen?” Sunrise asked.

“Sure.”

“Can I try?” the guy asked.

I handed him the Nintendo to play with. He got killed almost instantly because he didn't know what to do. I showed him how to move the little joystick.

“Where can I get one of these?” he asked.

“It's future technology,” I explained. “You don't have it yet. But if you give me and Sunrise a ride, you can play with it all the way to Cincinnati.”

He stuck out his hand and shook mine.

“The future is exactly where we're heading,” he said. “Hop in.”

A Long, Strange Trip

SUNRISE AND I PILED INTO THE BACK OF THE VAN. THE TWO

hippies got in the front. They introduced themselves as Peter and Wendy, which was easy for me to remember because of

Peter Pan

.

Wendy got behind the wheel so Peter could play with my Nintendo. It took a while to maneuver around the other cars, but eventually we were away from the Woodstock madness and driving on a country road. Wendy pulled into the first gas station she came to, and Peter hopped out to pump the gas.

“Hey,” he called to me through the window, “you got any bread, man?”

“Bread?” I asked. “Why, do you want to feed some birds or something?”

Sunrise broke up laughing and punched me in my shoulder.

“No man,

bread

!” Peter said. “Dollars. Pesos.

Spare change. Dig? Gas costs money, you know. We're running on empty.”

Sunrise opened a little fringed purse she had and gave Peter a five-dollar bill. It seemed kind of cheap to me. After all, we would be driving hundreds of miles to Cincinnati. But I had forgotten to bring any money with me, so I was in no position to judge.

Peter finished filling the tank and went to pay the attendant. When he came back, he handed Sunrise four quarters.

“Your change,” he said.

“She gets a dollar back from a five-dollar bill?” I asked, amazed. “How much was the gas?”

“35 cents a gallon!” Peter said. “That's highway robbery, man. It's 30 cents in Frisco.”

Gas for 30 cents a gallon! My mom told me she has paid more than four

dollars

a gallon! For a minute, I wondered if there might be a way to bring some 1969 gas back home with me.

Soon we pulled onto a highway and were making good time. We rolled down the windows, and everybody's hair was blowing in the wind. Everybody's but mine, of course, because I didn't have enough hair to blow. Wendy turned on the radio, and there was Jimi Hendrix, singing “Purple Haze” again. The three of them all said how great Woodstock had been despite the rain, the mud, the crowds, and the garbage. I asked Peter and Wendy why they had to get to California by Friday.

“We're going to an antiwar rally in San Francisco,” Peter said.

Antiwar. I had to think for a second. 1969. War. Oh, yeah. Vietnam.

“Why don't you two join us?” Wendy asked.

“I gotta get to Cincinnati,” I said.

“Me, too,” Sunrise said with a sigh. “I ran away from home.”

“How come?” we all asked her.

“My parents,” she said. “Screaming at me all the time. They hate my clothes, my music, my friends. Me.”

“Your parents don't hate you,” I told her.

It was probably the wrong thing to say. I didn't know her parents. For all I knew, they

did

hate her.

In any case, Sunrise clearly didn't want to talk about it. She just closed her eyes and shook her head, like nobody would ever understand her situation at home.

“How did you get to Woodstock?” I asked her.

“Hitched,” she said.

My mother told me that she hitchhiked a few times when she was younger but said I shouldn't do it because you never know what kind of psycho might pick you up. Of course, hitching a ride on a baseball card can be pretty dangerous too.

Peter had been absorbed with my Nintendo but stopped to ask how I got to Woodstock.

“Did you beam yourself over, like on

Star Trek

?” he asked. “Beam me up to Woodstock, Scotty!”

The girls laughed. I had no idea that

Star Trek

had been around so long. It bothered me a little that Peter was teasing me, but I couldn't blame him. If somebody walked up to me and said they were from another century, it would be hard to take them seriously.

I pulled out my Clemente card and passed it around. Peter said he was a baseball fan and seemed genuinely interested in the card.

“It says in the newspaper that the Pirates are playing in Cincinnati tonight,” I told them. “I need to talk to Roberto Clemente.”

“About what?” Sunrise asked.

“Well, this might sound strange,” I said, “but Clemente is going to die in a plane crash on December 31, 1972. Believe me, it's true. So I need to convince him not to get on that plane.”

“You are blowing my mind, man,” Peter said. “That's three years from now.”

“If he's going to die in 1972,” Wendy asked, “what are you doing here

now

? Why didn't you just go talk to him to 1972?”

“I didn't have a 1972 card,” I told them. “I always go to the year on the card. My dad gave me this one. I didn't even know it was a '69 until I got here.”

Nobody said anything for a few minutes. It seemed like they were trying to absorb what I had said. Maybe they thought I was crazy, or on drugs or something.

It was Peter who finally broke the silence. He put

down the Nintendo like it didn't matter to him anymore.

“Y'know, I like baseball too,” he said quietly. “I'm a Mets fan. They stink, I know. Last place in '62, '63, '64, '65, and '67. Next-to-last place in '66 and '68. But listen, man, there are other things in life that are more important than baseball.”

“Like what?” I asked him.

“Like ending the war!” he said, turning around to face me.

“Peter, don't get started,” Wendy told him. “He's too young to understand.”

“Do you know that the Constitution says that only Congress has the power to declare war?” Peter asked me. “And they never did! So tell me why 16,000 American kids were killed in Vietnam last year?”

“16,000?” Sunrise said. “Are you kidding?”

“No!” Peter said. “Look it up. I did.”

“He always does this,” Wendy told us.

“16,000 guys died, most of 'em under 21 years old!” Peter continued. “The whole war is a lie, y'know! North Vietnam didn't attack us. They're no threat to us. Does anybody even know why we're fighting them?”

“Because they're Communists?” Sunrise asked.

“So what?” Peter shouted. “It's just a different form of government. The Vietnamese aren't hurting anybody. Let 'em be Commies if they wanna be Commies!”

“Peter could get drafted into the army any day,”

Wendy explained. “If that happens, they'll probably send him to Vietnam. So we're fighting to end the war.”

“It's not just about

me

!” Peter said passionately. “The whole world is exploding before our eyes, man! They shot Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy last year. And did you hear about that guy Charles Manson who went nuts and murdered a bunch of people last week? It's insane! We have discrimination against blacks, women, and gays. People are starving, homeless, can't afford to go to a doctor when they're sick. And what's the government spending billions of dollars on? Sending astronauts to the

moon

!”

“Peter, please calm down,” Wendy said.

“Did you see that on TV a few weeks ago?” Peter continued. “Neil Armstrong stands on the moon and says it's a giant leap for mankind. I'll tell you what would be a giant leap for mankindâ”

“Enough already!” Wendy shouted. “You're bumming me out, man!”

Peter managed to calm himself down, but he wasn't finished.

“All I'm saying is, we've got infinite possibilities right here on

this

planet, man. We don't need to go to the moon. Our generation is gonna change everything. We're gonna end the war. We're gonna get Nixon impeached. Just you wait and see. Peace and love aren't just slogans, man. It's gonna be a revolution. You two should come with us to San Francisco and be part of it.”

Peter handed my baseball card back to me and said, “Or you can go watch Roberto Clemente hit a ball with a stick.”

We all fell silent. Peter picked up the Nintendo again and started fiddling with it. I wasn't about to go to California for an antiwar rally. But maybe he had a point. Maybe it was selfish of me to devote my energy to saving the life of one baseball player when there were so many bigger problems in the world.

I had never taken hippies seriously before. It had never occurred to me that they were anything more than silly cartoon characters who said “Groovy” all the time and walked around with peace signs, flowers, and funny clothes. To me and my friends, they were a joke, a Halloween costume.

Â

As I was thinking about all these things, I must have dozed off, because the next thing I knew, Wendy was shaking me awake.

“Rise and shine!”

I don't know how long I slept. It had to have been a long time, because it was dark out. Peter was in the driver's seat now, so they must have made a stop somewhere. Sunrise was still asleep, her head resting on my shoulder. It felt nice.

The van pulled to a stop.

“Where are we?” Sunrise asked, stretching.

“At a rest stop outside Cincinnati,” Peter said. “We've been on the road for 11 hours.”

We used the restrooms, and I asked Peter if he

would be able to drop me off at Crosley Field, where the Cincinnati Reds played. He said he didn't know where it was.

“Do you have a GPS?” I asked.

“A what?”

“Forget it.”

We piled back into the van, and Sunrise was able to direct us to Crosley Field, which was only about a mile from her house.

“Can we drive you home?” Wendy asked Sunrise.

“I'm not sure I'm ready to face my parents yet,” she said. “Can I hang with you a while, Stosh? Until I get my courage up?”

“Sure,” I said.

I saw the big

CROSLEY

sign, and we pulled over in front of the ballpark. Peter and Wendy got out of the van to say good-bye.

“Last chance,” Peter said. “You can still come with us to Frisco.”

I shook my head. “Thanks, anyway,” I said.

Peter and Wendy hugged both of us. They had been incredibly nice, driving us all the way to Cincinnati.

“Hey, man, I gotta ask you,” Peter said, “if you've really seen the future, what's gonna happen? Did we change the world? Will the war end? Did all our protesting make a difference?”

I had been expecting him to ask that question. I wasn't sure how to answer it. Of course the world changed since 1969. A lot. But I'm no genius. I didn't

know what caused the changes. Maybe hippies like Peter and Wendy were a part of it. Or maybe the changes would have taken place no matter what they did. Who really knows for sure?

“The war is going to end,” I finally told them. “President Nixon is going to resign. The women's movement and gay rights movement are going to really take off. And America is going to elect a black president in 2008.”

“No way!” Peter said. “Far-out!”

Peter and Wendy were ecstatic, jumping up and down and marveling at how their generation was actually going to make a difference and change the world for the better.

I went to give Peter a high five and he went to give me a low five. We met somewhere in the middle.

“I bet after this the government will never get away with starting a senseless, undeclared war against some country that was no threat to us,” Peter said. “No way America is gonna make

that

mistake again, huh?”

“Uh⦔ I said, “listen, I gotta go find Roberto Clemente.”

“Peace, man,” Peter said, giving me a bear hug.

“Hey, Stosh, I want to give you something,” Wendy told me. She climbed in the van and came back out with a string of love beads and a headband. Wendy put the beads around my neck while Sunrise adjusted the headband.

“There,” Wendy said. “Now you look like one of us.”

I thanked them, and Sunrise took my hand. We were walking away from the van when Peter rolled down the window.

“Hey, one more thing,” he called out. “If you really know the future, who's gonna win the World Series this year?”

The 1969 World Series. I tried to remember my baseball history. Oh, yeah. That was a famous one.

“The Miracle Mets,” I told him. “They're gonna beat Baltimore in five games.”

“The

Mets

?” Peter said, bursting out in laughter. “You gotta be kidding me! I mean, I can believe Nixon resigning. I can believe there will be a black president. But the Mets winning the World Series? You must be joking!

Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha!

”

I could still hear him cackling as the van pulled away.