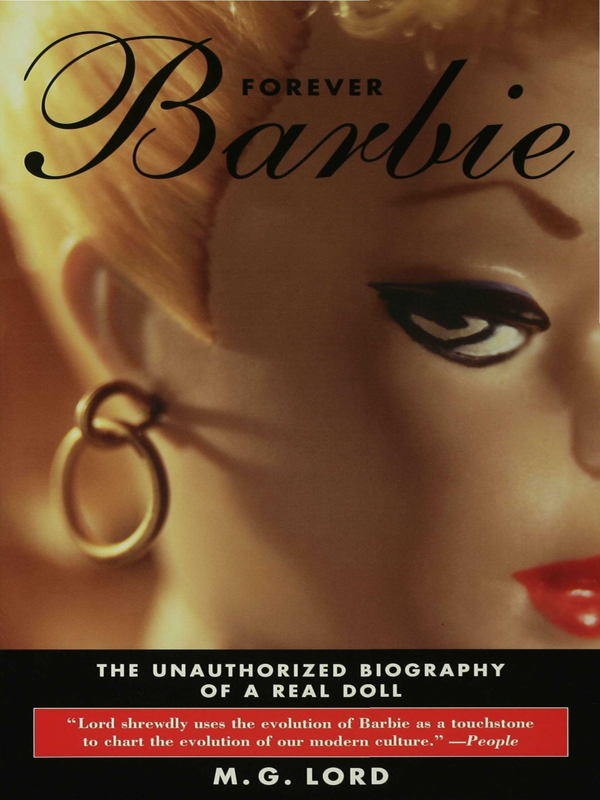

Forever Barbie

Authors: M. G. Lord

"Important, riveting, and original

... a

dazzling, provocative read.

Everybody interested in American culture will want to savor this book."

—BLANCHE WIESEN COOK,

author of

Eleanor Roosevelt

"With verve and wit, M. G. Lord rehabilitates Barbie and returns her to us as

rebel, role model, and goddess."

—BARBARA EHRENREICH,

author of

Nickel and Dimed

"Beautifully written . . . Lord examines Barbies ideological pros and cons,

tracking her commercial and sociological evolution and interviewing numerous

Barbie collectors, impersonators, and even mutilators.

"

—ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY

"Ms. Lords exhaustive reporting leaves little doubt that Barbie is a powerful

cultural icon, historically reflective of societal views of women."

—THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

"An elegant meditation on the meaning of Barbie. . . . Will shake up your

rusty preconceptions and make you think of Americas most celebrated plastic

doll in ways you never have before.

"

—SUSAN FALUDI,

author of

Backlash

"This book is not just about a doll, but about the lives of women over four

decades. It is a brilliant and entertaining analysis of the vestigial remains of

the Feminine Mystique that are still infecting our daughters.

"

—BETTY FRIEDAN

"M. G. Lord has transcended her ostensible subject to produce a work of

shrewd, illuminating, and witty social history.

"

—J. ANTHONY LUKAS,

author of

Common Ground

The

Unauthorized

Biography

of a

Real Doll

FOREVER

BARBIE

M. G. LORD

In memory of

Ella King Torrey

AUTHOR'S NOTE: This book was prepared

in cooperation with Ella King Torrey,

who began researching Barbie

in 1979 as part of a Yale University

Scholar of the House project.

Copyright © 1994. 1995, 2004 by M. G. Lord

Preface copyright 2004 by M. G. Lord

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from

the Publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 1994 by William Morrow and Company Inc. First paperback edition published

in the United States of America in 1995 by Avon Books. This paperback edition published in 2004 by Walker Publishing Company,

Inc.; published simultaneously in Canada by Goose Lane Editions.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions. Walker & Company,

104 Fifth Avenue. New York. New York 10011.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

available upon request

eISBN: 978-0-802-71923-2

Original book design by Alexander Knowlton

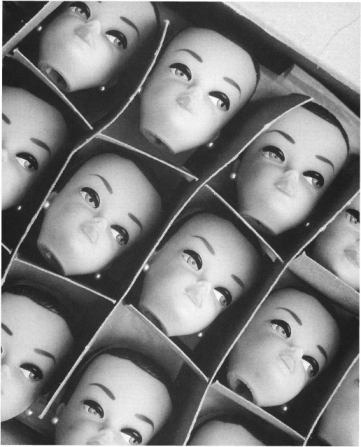

Fashion Queen Doll Heads (frontispiece): Barry Sturgill

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at

www.walkerbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

CONTENTS

Much has happened in the ten years since

Forever Barbie

teetered into the marketplace on its steep stiletto mules. After September 11, 2001, Barbie became a symbol of something larger

than her shapely self. She is everything that Islamic extremists hate: an unapologetically sexual, financially independent,

unmarried Western woman. And with all the cars she's amassed, there's no getting around the fact that she drives, an activity

forbidden to women in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—where, incidentally, she has been banned since 1995. In an annual campaign

timed to coincide with the beginning of the school year, that country's religious police blanket schools and streets with

posters decrying her "revealing clothes" and "shameful postures."

A lot has also happened at Mattel. Former chief executive officer Jill Barad, who could do no wrong in 1994, was not doing

very much right in 2000, when she resigned. In the 1980s, when Barad joined the Barbie team, the doll was realizing about

$250 million in annual business. By the time she left, due in large part to her efforts, Barbie's sales had reached $1.7 billion.

Mattel's pushing, pushing, pushing to reach that plateau, however, left many resentful—especially in 1997, when collectors,

in what the press called the "Holiday Barbie" scandal, shelled out full price for "limited edition" seasonal dolls, only to

discover that Mattel had overproduced them and by January was dumping them with discounters and cable-TV networks.

Under Barad, Mattel eliminated rival toymakers by buying them, regardless of the cost. It ingested Pleasant Company in 1998

and by 2003 had thoroughly Barbie-ized its tony American Girl dolls. The original dolls, accessorized to reflect periods in

American history, came with bookstraps and school desks; the Mattel version has a glitter guitar, a bikini, and a boogie board.

Mattel's big mistake, however, occurred in the spring of 1999, when Barad acquired the Learning Company for more than what

many experts believed it to be worth. That fall, when the Learning Company delivered a $105 million loss, Mattel's stock declined

by seventy percent of its value. Four months later Barad was out, though not exactly in the cold. Her severance package was

more than $40 million.

Such management upheavals, however, are not new at Mattel. In the 1970s, Barbie inventor Ruth Handler was thrown out of the

company she founded before pleading no contest to conspiracy, mail fraud, and falsifying SEC information. With time, however,

the world ceased to care that she was a felon. From the middle 1980s until her death from cancer in 2002, she signed autographs

and accepted adulation at all major events celebrating the doll.

Mattel's profits have also risen and fallen cyclically. Barbie's sales tanked in the seventies, but soared in the eighties

and early nineties, when the baby boomers had their children. When the boomer's children have children, I predict sales will

peak again.

At age forty-five, despite that body, Barbie has become a traditional toy— not a bad girl, but "Mrs. Smarty-pants," as one

nine-year-old recently called her. I watched this girl and her friends play with the 2003 Christmas season's must-have dolls,

a street-smart bunch called Bratz, not made by Mattel. But as soon as there was trouble—one of the Bratz got sick—Dr. Barbie

was summoned. She was a professional, an authority figure; the girls gave her an English accent. Because of Barbie's mutability,

I doubt any new doll will ever eclipse her. Even at the peak of her sales, Barbie was the salutatorian, not valedictorian,

of the toy market—coming in second at the holidays to the latest flash in the pan.

This business of graciously coming in second—of not being pushy or grabby—is a component of femininity, right up there with

good grooming. A set of coded behaviors that has nothing to do with biological femaleness, femininity existed long before

Barbie, and it is something mothers tend to teach their daughters, even though they themselves may feel ambivalent about it.

When it comes to parental ill will toward Barbie, I believe femininity is the toxin; Barbie is the scapegoat.

In 2002 Dr. Barbie took on a new role—obstetrician for her best friend Midge. This pregnancy was not without precedent. In

response to consumer demand, Mattel has tried for decades to accessorize Barbie with a baby without making her a mother. (The

first solution was "Barbie Baby-Sits" in 1963.) The "Happy Family" Midge came with a child, a husband, and a bulging plastic

abdomen attached to its torso with magnets. In terms of ickiness, it rivaled Growing Up Skipper, a version of Barbie's little

sister that sprouted breasts when you twisted its arm. The doll was not a success in the United States; parents believed it

encouraged teen pregnancy. Just before Christmas, Wal-Mart yanked Midge from its shelves though it continued to sell well

in Canada.

Near Barbie's forty-fifth birthday in 2004, Mattel made what was supposed to be a dramatic announcement: Barbie had split

from Ken. To many, however, this came as no surprise; Barbie's roving eye has for years been an open secret in Toyland. As

early as 1972, for example, photographer David Levinthal caught Barbie in compromising positions with G.I. Joe. (Images from

the series appear in this book.)

Barbie's behavior is consistent with what I have come to term Beverly Hills Matron Syndrome, which afflicts many women in

midlife. The symptoms include ditching one's longtime consort, sporting age-inappropriate clothing (the post-Ken Barbie comes

with racy new beachwear), and dating unsuitable younger men—anonymous male dolls that, if not born yesterday, were probably

fabricated within the last eighteen months. I suspect, however, that working with a Toyland therapist, Barbie may recover

and reconcile with Ken, who, having disappeared for a while, will be ideally positioned for an attention-grabbing comeback.

When asked to comment on the implications of the latest Barbie, I often observe that today's "new" model was issued in a slightly

different form twenty or thirty years earlier. In the last decade, while much has indeed happened, it seems precious little

has changed. At Mattel as in Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun.

Like the doll itself,

Forever Barbie

was not made by a lone extremist. Thanks to Paul Bresnick for coming up with the idea, and Janis Vallely for convincing him

that I was the writer to implement it. To Sylvia Plachy, for those amazing photographs, as well as that weekend with Ella

King Torrey in Niagara Falls. To Amy Bernstein, Corby Kummer, and Judith Shulevitz, for performing surgery without an anesthetic.

To Anna Shapiro, the original Boho Barbie, for editorial and conceptual guidance. To Glenn Horowitz, for keeping me on track,

and to the friends who kept my thinking on track: May Castleberry, Anne Freedgood, Ben Gerson, Marianne Goldberger, Caroline

Niemczyk, Ellen Handler Spitz, and Abby Tallmer.

Because this book required extensive trips to Los Angeles and a monastic year of writing on Long Island, I must express thanks

geographically: to the California contingent—Victoria Dailey, Barbara Ivey, Mike Lord, and Nancy Lord; the Sag Harbor contingent—Laurel

Cutler, Dorothy Frankel, and Carol Phillips; and, in cyberspace, the Echo contingent—Marisa Bowe, Jonathan Hayes, Stacy Horn,

and NancyKay Shapiro.

On the research front, thanks to Tom Fedorek, Caroline Howard, Jeremy Kroll, Donna Mendell, and Jessy Randall. And to Mary

Lamont, my stalwart transcriber.

Nor could I have written this without certain spokespeople for the under-twelve set: Polly Bresnick, Honor McGee, Meredith

Niemczyk, Gabriel Nussbaum, Lilly Nussbaum, and Heather O'Brien.

Many people interviewed for this book provided background rather than extensive quotations. For a consumer-watchdog look at

the toy industry and at children's television, thanks to Diana Huss Green and Peggy Charren. On the role of stylists in the

fashion industry, thanks to Michele Pietre and Debra Liguori. On family dynamics and eating disorders, thanks to Laura Kogel

and Lela Zaphiropoulos of the Women's Therapy Center Institute. On goddess iconography in visual art, thanks to Monte Farber

and Amy Zerner. For an insider's perspective on collecting, thanks to Joe Blitman, Karen Caviale, Beauregard Houston Montgomery,

and Marlene Mura. And to Gene Foote, for permitting Geoff Spear to photograph his "girls."

Then there were the friends who acquainted me with books, artwork, ideas, and people that I needed to know: Charles Altshul,

Lauren Amazeen, Vicky Barker, Janet Borden, Russell Brown, Susan Brownmiller, Jill Ciment, Suzanne Curley, Deirdre Evans-Prichard,

Eric Fischl, Henry Geldzahler, Arthur Greenwald, Vicki Goldberg, April Gornik, John G. Hanhardt, Lydia Hanhardt, Linda Healey,

Phoebe Hoban, Margo Howard, Susan Howard, Deborah Karl, Delores Karl, Chip Kidd, Katie Kinsey, Jennifer Krauss, David Leavitt,

Karen Marta, Yvedt Matory, Rebecca Mead, Louis Meisel, Susan Meisel, Anne Nelson, Dan Philips, Kit Reed, Bill Reese, Ken Siman,

Barbara Toll, Frederic Tuten, Miriam Ungerer, Janet Ungless, and Katrina Vanden Heuvel. Also, Camille Paglia never missed—or

failed to forward—a Barbie reference in

TV Guide.

And finally, thanks to Glenn Bozarth and Donna Gibbs at Mattel, who deigned to give me access, and to all the present and

former Mattel employees who told their stories. Without them, Barbie's synthetic tapestry would have been vastly less rich.

In 2004, with the reissue of

Forever Barbie,

I owe thanks to yet more people. To George Gibson, my publisher, and Eric Simonoff, my agent, for continuing to believe in

this book. To my friends Brenda Potter and Michael Sandier, who, with Susan Brodsky and Chris Thalken, organized an eye-opening

focus group. To Emma Thalken, Tatjana Asia, and Brittany Campbell for their surprising insights into Barbie's evolving identity.

To the Guerilla Girls, for resuscitating interest in the Lilli doll. And to Christine Steiner for those exhausting requisites

for writerly production—attention and support.