Forever Barbie (5 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Lilli's cartoon antics fit right in with the

Bild Zeitung's

sordid, sensational stories. A golddigger, exhibitionist, and floozy, she had the body of a Vargas Girl, the brains of Pia

Zadora, and the morals of Xaviera Hollander. Beuthien's jokes usually hinged on Lilli taking money from men and involved situations

in which she wore very few clothes. Male wealth was of far greater interest to Lilli than male looks; she flung herself repeatedly

at balding, jowly fat cats.

In one typical cartoon, Lilli appears in a female friend's apartment concealing her naked body with a newspaper. The caption:

"We had a fight and he took back all the presents he gave me." In another, a policeman warns that her two-piece bathing suit

is illegal on the boardwalk. "Oh," she replies, "and in your opinion which part should I take off?" In yet another, she shouts

her phone number to a female friend on the street, hop-ing the rich-looking man nearby will overhear.

Her debut cartoon, which ran on July 24, 1952, set the tone for the others. It shows her with a gypsy fortune-teller begging,

"Can't you give me the name and address of this tall, handsome, rich man?"

Even people inured to the peculiarities of Barbie's body might cringe at the sight of the doll based on Lilli. Unlike Barbie,

Lilli doesn't have an arched foot with itty-bitty toes. She doesn't even have a foot. The end of her leg is cast in the shape

of a stiletto-heeled pump and painted a glossy black. Never mind that her leg is a fetishistic caricature; never mind that

she is hobbled, easily pushed into a horizontal position; that she might want to play tennis sometime or walk on the beach.

Poor Lilli can never take the monstrous slipper off.

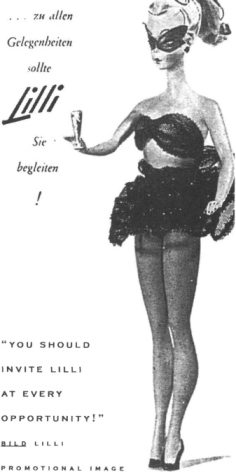

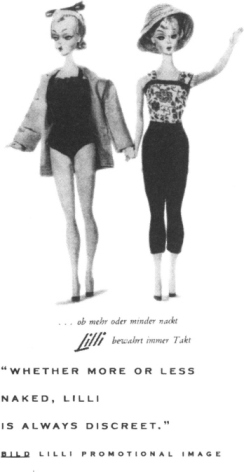

Sculpted by doll designer Max Weissbrodt, Lilli was never intended for children: She was a pornographic caricature, a gag

gift for men, or even more curious, for men to give to their girlfriends in lieu of, say, flowers. "Die

hochsten Herm haben Lilli gem"

—"Gentlemen prefer Lilli," says a brochure promoting her wardrobe, over a picture of the doll in a short skirt that has blown

up above her waist. It adds: "Whether more or less naked, Lilli is always discreet."

("Ob mehr oder minder

nackt Lilli bewahrt immer Tackt.

")

Like Barbie, Lilli has an outfit for every occasion, but they aren't the sort of occasions in which nice girls find themselves.

In a dress with a low-cut back, Lilli can be "the star of every bar"; in a tarty lace one, she can rendezvous for a five o'clock

tea—either in a cafe* or (wink) in private. Lilli isn't just a symbol of sex, she is a symbol of illicit sex.

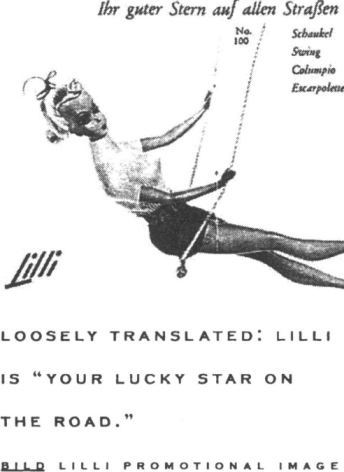

"You should take Lilli with you everywhere," the brochure advises men. As a "mascot for your car," Lilli promises a "swift

ride"

("beschwingte

Fahrt").

The nature of this "swift ride" is suggested by Lilli's photo. In a tight sweater and microscopic shorts, she sits on a swing,

her outstretched legs slightly splayed—a pornographic recasting of Fragonard's erotic

The

Swing.

The brochure mentions that "children swoon" over Lilli; but the very notion of "swooning"—the way one "swoons" over a rock

star—has a weird carnal ifinuendo, implicitly sexualizing kids.

Just what did German men do with the doll? "I saw it once in a guy's car where he had it up on the dashboard," said Cy Schneider,

the former Carson/Roberts copywriter who wrote Barbie's first TV commercials. "I saw a couple of guys joking about it in a

bar. They were lifting up her skirts and pulling down her pants and stuff."

Lilli is more, however, than a male wet dream; she is a Teutonic fantasy. And her Germanness is a critical part of her identity.

Lilli reminds me of Maria Braun in

The Marriage of

Maria Braun,

Rainer Werner Fass-binder's allegorical 1979 film about the relationship between the two parts of then-divided Germany. Not

only does Hanna Schygulla, the relentlessly Aryan actress who portrays Maria, closely resemble Lilli; for much of the movie

she wears the same hairstyle—a flaxen ponytail with poodle bangs. One gets the sense that Lilli, like Maria, has endured great

privation during the war, and that even if it means using men, she will not starve again. Although Fassbinder is not around

to clear up the mystery, one has to believe he was familiar with the Lilli cartoon character—so similar to Lilli's are Maria's

clothes, makeup, and behavior.

In Fassbinder's movie, the parallel between Maria and the Federal Republic is clearly defined: Maria kills a black American

G.I.; her German husband takes the fall, and she remains loyal to him while he is in jail—a situation analogous to the prisonlike

condition of East Germany before 1989. Her loyalty, however, does not preclude exchanging sexual favors for cigarettes, silk

stockings, and ultimately, corporate perks. Lilli first appeared in 1952, when the so-called German economic miracle was under

way, though far from fully realized. And while Lilli doesn't bear the metaphorical burden of a marriage to the East, it's

hard not to view her pursuit of wealth as similar to that of West Germany. She is the vanquished Aryan, golddigging her way

back to prosperity.

Ruth Handler first encountered the Lilli doll when she was shopping in Switzerland on a family vacation. "We were walking

down the street in Lucerne and there was a doll—an adult doll with a woman's body—sitting on a rope swing," Ruth told me,

though she has in other interviews placed this epiphany in Zurich and Vienna. Her daughter Barbara, in her mid-teens and well

past the age for dolls, wanted Lilli as "a decorative item" for her room. Ruth bought three—two for Barbara, one for herself.

"I didn't then know who Lilli was or even that its name was Lilli," Ruth said. "I only saw an adult-shape body that I had

been trying to describe for years, and our guys said couldn't be done."

"Our guys" were the male designers at Mattel. Since Barbara was a child, Ruth had tried to get them to develop a doll with

a woman's body. She got the idea watching Barbara play with paper dolls who were "never the playmate or baby type," but rather

"the teenage, high-school, college, or adult-career type."

"Through their play," Ruth said, Barbara and her friends "were imagining their lives as adults. They were using the dolls

to reflect the adult world around them. They would sit and carry on conversations, making the dolls real people. I used to

watch that over and over and think: If only we could take this play pattern and three-dimensionalize it, we would have something

very special."

Special

was not how the male designers saw it. It was costly. In America, they told Ruth, it would be impossible to make what she

wanted —a woman doll with painted nails " Othing" that had "zippers and darts and hemlines"— for an affordable price.

"Frankly," Ruth recalled, "I thought they were all horrified by the thought they were of wanting to make a doll with breasts."

But just because the dolls couldn't be made in America didn't mean they couldn't be made. In July 1957, Jack Ryan took off

for Tokyo to find a manufacturer for some electronic gadgets he had designed. "Just as I was leaving," he said, "Ruth stuck

this doll into my attache* case and said: 'See if you can get this copied.' " The doll, of course, was Lilli.

Jack was accompanied on the trip by Frank Nakamura, a recent graduate of Los Angeles' Art Center School whom Mattel had hired

as a product designer in April. A United States citizen, Nakamura was also fluent in Japanese; during the war, he taught the

language in a school run by the U.S. Military Intelligence Service at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. When the war

ended, he was sent to Japan to debrief Japanese soldiers on their battle experiences and report their stories to General MacArthur.

Frank "knew his way around Japan very well," Jack said. "And in Japan, it's more important to know your way around and to

be able to make connections than it is here. Here you walk into any office and you're doing business right away on face value.

It's not so in Japan."

The trip did not begin auspiciously. Ryan, Frank recalled, became edgy when the plane took off. He had an odd phobia for an

aerospace engineer: He was afraid to fly. Nor did things go smoothly on the ground. Frank contacted numerous manufacturers,

none of whom was equipped to make vinyl dolls. After three weeks, Ryan returned to California.

Part of the problem was Lilli herself; she didn't exactly capture the hearts of the Japanese. "The Lilli doll looked kind

of mean—sharp eyebrow and eyeshadow and so forth," Nakamura said. "And Japanese people didn't like it at all." But Frank

pressed on, and by the time Elliot joined him early August, Kokusai Boeki m Kaisha (KBK), a Tokyo-based novelty maker, was

ready to cut a deal.