Forever Barbie (4 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Toys have always said a lot about the culture that produced them, and especially about how that culture viewed its children.

The ancient Greeks, for instance, left behind few playthings. Their custom of exposing weak babies on mountainsides to die

does not suggest a concern for the very young. Ghoulish though it may sound, until the eighteenth century, childhood didn't

count for much because few people survived it. Children were even dressed like little adults. Although in 1959, much fuss

was made over Mattel's "adult" doll, the fact was that until 1820 all dolls were adults. Baby dolls came into existence in

the early decades of the nineteenth century along with, significantly, special clothing for children.

Published in 1762, Rousseau's

Emile,

a treatise on education, began to focus attention on the concerns of youngsters, but the cult of childhood didn't take root

until Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837. "Childhood was invented in the eighteenth century in response to dehumanizing

trends of the industrial revolution," psychoanalyst Louise J. Kaplan has observed. "By the nineteenth century, when artists

began to see themselves as alienated beings trapped in a dehumanizing social world, the child became the savior of mankind,

the symbol of free imagination and natural goodness."

The child was also a consumer of toys, the making of which, by the late nineteenth century, had become an industry. Until

World War I, Germany dominated the marketplace; but when German troops began shooting at U.S. soldiers, Americans lost their

taste for enemy playthings. This burst of patriotism gave the U.S. toy industry its first rapid growth spurt; its second came

after World War II, with the revolution in plastics.

Just as children were "discovered" in the eighteenth century, they were again "discovered" in post-World War II America—this

time by marketers. The evolution of the child-as-consumer was indispensable to Barbie's success. Mattel not only pioneered

advertising on television, but through that Medium it pitched Barbie directly to kids.

It is with an eye toward using objects to understand ourselves that I beg Barbie's knee-jerk defenders and knee-jerk revilers

to cease temporarily their defending and reviling. Barbie is too complicated for either an encomium or an indictment. But

we will not refrain from looking under rocks.

For women under forty, the implications of such an investigation are obvious. Barbie is a direct reflection of the cultural

impulses that formed us. Barbie is our reality. And unsettling though the concept may be, I don't think it's hyperbolic to

say: Barbie is us.

I

t is hard to imagine Mattel Toys headquartered anywhere but in southern California. A short drive from Disneyland, minutes

from the beach, it is in a place where people come to make their fortunes, or so the mythology goes, where beautiful women

are "discovered" in drugstores, and a man can turn a mouse into an empire. Barbie could not have been conceived in Pawtucket,

Rhode Island, where Hasbro is located, or Cincinnati, Ohio, where Kenner makes its home. Barbie needed the sun to incubate

her or, at the very least, to lighten her hair. This is not to say that Hawthorne, where Mattel had its offices until 1991,

is anything but a dump—a gritty industrial district that cries out for trees. But it is a dump with a glamour-queen precedent:

In 1926, Marilyn Monroe was born there.

Of course it's inaccurate to say Barbie was "born" anywhere. The dolls were originally cast in Japan, making, I suppose, Barbie's

birthplace Tokyo. But Barbie's "parents," Ruth and Elliot Handler, are very much southern Californians—of the fortune-making

variety—who fled their native Denver, Colorado, in 1937.

California was a different place back then: neither stippled with television antennas nor linked with concrete cloverleaf.

The McDonald brothers wouldn't raise their Golden Arches for another fifteen years. Thanks to the Depression, the Golden State

had lost some of its glister. Okies and Arkies poured in from the ravaged Dust Bowl; and for many, the land of sunshine and

promise was just as gray and bleak as the place they had left.

Not so for the Handlers. Just twenty-one when they uprooted, they were optimists; and because they believed in the future

they were willing to take risks. The youngest of ten children, Ruth was a stenographer at Paramount Pictures; Elliot, the

second of four brothers, was a light-fixture designer and art student; and their first gamble was to chuck their jobs and

start their own business, peddling the Plexiglas furniture that Elliot had been building part-time in their garage. The wager

paid off: In the first years of World War II, they expanded into a former Chinese laundry and hired about a hundred workers.

They made jewelry, candleholders, even a clear-plastic Art Deco airplane with a clock in it.

Wartime shortages derailed that venture, but the Handlers remained on track. In 1945, they started "Mattel Creations" with

their onetime foreman, Harold Matson, whose name was fused with Elliot's to form Mattel. Matson, however, did not love gambling

with his life savings; he sold out in 1946, making him the sort of asterisk to toy history that short-term Beatle Pete Best

was to the history of popular music.

Elliot not only believed in the future, he believed in futuristic materials— Plexiglas, Lucite, plastic. He set up Mattel

to manufacture plastic picture frames, which, because of wartime rationing, ironically ended up being made of wood. When the

war ended, however, it was the Ukedoodle, a plastic ukelele, that secured Mattel's niche in the toy world. A popular jack-inthe-box

followed, and by 1955, the company was worth $500,000.

Although Barbie wouldn't be introduced for another four years, Mattel, in 1955, paved the way for the sort of advertising

that would make her possible. It was a big year for child culture: Disneyland had opened in July and Walt Disney, who seemed

to have a golden touch with the under-twelve set, was preparing to launch a TV series,

The Mickey Mouse Club.

No toy company had ever sponsored a series before, and ABC, Disney's network, wanted to give Mattel the chance. There was

just one catch: ABC demanded a year-long contract that would cost Mattel its entire net worth.

Ralph Carson, cofounder of Carson/Roberts, Mattel's advertising agency, thought the Handlers would be hesitant. He brought

Vincent Francis, ABC's airtime salesman, to Elliot's office to make the pitch. What he failed to consider, however, was the

Handlers' willingness to gamble.

The presentation "took fifteen or twenty minutes," Ruth recalls, and she and Elliot were "ready to jump out of our skins with

excitement." But before they said yes, they consulted their comptroller, Yasuo Yoshida.

"Yas," Ruth recalls having said, "what would happen if we didn't bring much out of this? Would we go broke? And Yas's answer

was: 'Not broke— but badly bent.' "

"Okay," Elliot remembers telling him, "we'll try the bent."

In Mattel's commercial, a little boy stalked an elephant with a toy called the Burp Gun; when the child fired, the film of

the animal ran backward, causing it to appear to retreat. Kids loved the ad, and by Christmas the gun had sold out.

The Handlers' move, however, did more than create record sales for a single product in a single year. Before advertisers could

pitch directly to kids, selling toys had been a mom-and-pop business with a seasonal focus on Christmas. But once kids could

actually see toys on television, selling them became not only big business but one that took place year-round.

Ironically, in December 1955,

Time

magazine ran a photo of Louis Marx, founder of Louis Marx & Company, Inc., on its cover. He was king of the old-time toy industry—an

industry that Mattel and Carson/Roberts were well on their way to making obsolete. Marx sneered at advertising. Although his

company had had sales of $50 million in 1955, it spent a meager $312 on publicity. Mattel, by contrast, which had sales of

$6 million, spent $500,000; it also pioneered marketing techniques that would send Marx and his ilk the way of the dinosaurs.

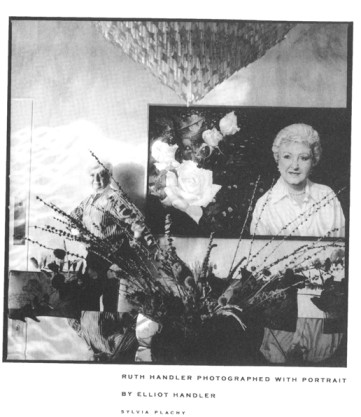

IN 1993, RUTH AND ELLIOT SHARED SOME REMINISCENCES with me in their Century City penthouse. With its gray marble floor, white

pile carpet, grand piano, and vast semicircular wet bar, the dwelling is a far cry from the furnished one-room apartment they

shared when they were married in 1938. Their daughter, Barbara, after whom the doll was named, was born in 1941; their son

Ken, who also gave his name to a doll, in 1944, during Elliot's year-long hitch in the U.S. Army.

Together since they were sixteen, they have weathered things that might have daunted a lesser couple: Ruth's radical mastectomy

in 1970; her indictment in 1978 by a federal grand jury for mail fraud, conspiracy, and making false statements to the Securities

and Exchange Commission; and, after having pleaded no contest to the charges, her conviction, leading to a forty-one-month

suspended sentence, a $57,000 suspended fine and 2,500 hours of community service, which she has completed. In 1975, they

survived expulsion from the company they built. Theirs is the sort of romance that seems to happen only in the movies—or used

to happen, before the fashion for verisimilitude precluded not only "happily ever after" but "ever after."

They have not grown to resemble each other, as many couples do. Ruth is compact and gregarious. She marches into a room with

a combination of authority and bounce, rather like Napoleon in pump-up, air-sole Nikes. And indeed, on the two occasions I

met her, once at home and once at Beverly Hills' Hillcrest Country Club, she was wearing sneakers and a stylish warm-up suit.

Her hair is short and steely. She can be irresistibly charming; she's cultivated the ability to listen as if you were the

most fascinating conversationalist in the world. But if your talk takes a turn she doesn't like, she can wither you with a

glance.

"When she walks, the earth shakes," said her son Ken, a philanthropist, entrepreneur, and father of three who lives in New

York's West Village. "She's a little woman, seventy-six years old, and the earth shakes."

Elliot is tall, lanky, and laconic. He lets his wife do most of the talking, occasionally interrupting with a sardonic aside.

He dresses as casually as Ruth, wearing short-sleeve polo shirts on the two occasions I met him. Very little, I suspect, gets

by him: he strikes me as a keen observer.

Elliot's paintings hang on nearly every wall of the apartment. One composition depicts an orchid on a mirrored table; in the

foreground, blue and white jewels spill opulently from a case. Another shows voluptuous red and green apples in front of a

city scape. Yet another has as its principal element a giant pigeon. Often, these forms are displayed against a flat cerulean

sky with clouds—a sky that recalls Magritte's and that, as the objects are painted many times larger than life and in intense

Day-Glo colors, heightens their surreality.

There was a time, a little less than ten years ago, when the room was a museum, housing the Handlers' multimillion-dollar

collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. A wintry Norwegian landscape by Claude Monet contrasted with

brighter, sunnier spots by Camille Pissarro, Fernand Leger, and Andre Derain. Pierre-Auguste Renoir's

Baigneuse

and Picasso's

Baigneuse au Bord de la Mer

shared wallspace with Amedeo Modigliani's

Tete de Jeune Fille.

But considering whose success made the collection possible, perhaps the most intriguing canvas was Moise Kisling's

La Jeune Femme Blonde:

a standing female nude, slightly stouter than Barbie, with her hair pulled back in a Barbie-esque ponytail.

In 1985, however, at the height of the art market, the Handlers put their paintings on the block at Sotheby's in New York.

"One day I said, 'This place is no good for an art collection'—too much glass, too much window, too much daylight," Elliot

explained with a smile. "We had to keep the drapes closed. So I said, 4Aw, to hell with it, I'm painting now.' "

If one were to believe in astrology, as many Californians do, one would suspect something strange and powerful was going on

in the heavens over Hawthorne in 1955. Not only had Mattel caused an earthquake in the toy business, but the company hired

Jack Ryan, a wildly eccentric, Yale-educated electrical engineer whose sexual indiscretions, extravagant parties, and sometimes

autocratic management style would shake the company from within.

For Elliot Handler, hiring Jack was a great triumph. Elliot had initially met him when he pitched Mattel an idea for a toy

transistor radio. Children's toys were not, however, Ryan's forte; a member of the Raytheon team designing the Sparrow and

Hawk missiles, he made playthings for the Pentagon. But Elliot sensed that Jack had what Elliot needed: Jack knew about torques

and transistors; he understood electricity and the behavior of molecules; he had the space-age savvy to make Elliot's high-tech

fantasies real. Elliot courted Ryan for several years, sweetening his offer until Ryan had a remarkable contract: one that

permitted him a royalty on every patent his design group originated; one that swiftly transformed him into a multimillionaire.

Ryan "had a funny little body, very compact, and a kind of bird puffy chest—like he had just puffed himself up," recalled

novelist Gwen Davis, who had met him through his fourth wife, Zsa Zsa Gabor. His hair appeared "painted on, like Reagan's,

and he had a very peculiar tan that looked as if it might have been makeup." At his parties, he wore clothing that was very

non-Brooks Brothers—khaki jackets with golden epaulets, imaginary uniforms, fantasy costumes for his fantasy life.

The setting for this strange life was the castle he built in Bel Air, on the site of the five-acre, eighteen-bathroom, seven-kitchen

estate that had belonged to silent-screen star Warner Baxter. In Jack's mind, "residence" was a synonym for "theme park."

He gave dinner parties in a tree house with a glittering crystal chandelier and occasionally forced his guests to down victuals

without utensils in a tapestry-ridden, vaguely medieval curiosity that he called the Tom Jones Room. "He ruined a perfectly

good English Tudor house by putting turrets on the end of it," chided Norma Greene, the retired liaison between Ryan's design

group and Mattel's patent department.

But the castle was not all lighthearted fun and games. It also had a dungeon— Zsa Zsa described it as a "torture chamber"—painted

an ominous black and adorned with black fox fur. Over the years the castle housed, often simultaneously, his first wife Barbara,

his two daughters, his brother Jim, multiple mistresses, one or two fellow engineers, and a group Zsa Zsa called "Ryan's Boys,"

twelve UCLA students who did work around the place in exchange for room and board.

Zsa Zsa never moved in with Jack; but even with her own house as a refuge, she could only endure seven months of marriage.

"Jack's sex life would have made the average

Penthouse

reader blanch with shock," she observed in her autobiography,

One Lifetime Is Not Enough.

Meanwhile, in Hamburg, Germany, around the world from Mattel, 1955 was a key year for another designer who had a major influence

on Barbie. Reinhard Beuthien, a cartoonist, had created the comic character Lilli for the

Bild Zeitung;

on August 12 of that year, Lilli acquired a third dimension. The Bavaria-based firm of Greiner & Hauser GmbH issued her as

an eleven-and-a-half-inch, platinum-ponytailed, Nefertiti-eyed, fleshtone-plastic doll.