Forever Barbie (8 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Barbie's similarity to Brown's brave, new, vaguely selfish and decidedly subversive heroine has more than whimsical ramifications.

It makes Barbie an undercover radical. Brown was "the first spokeswoman for the revolution," say Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth

Hess, and Gloria Jacobs in

Re-

Making Love: The Feminization of Sex,

even though today Brown is "a woman whom many feminists would be loath to claim as one of their own." Long before feminism

was a part of the American political vocabulary, they point out, droves of women bought Brown's book—an antimarriage manifesto

and plea for women's financial liberation and sexual autonomy disguised as a breezy volume of self-help.

In choosing clothes, Brown urges: "Copycat a mentor with better taste than yours." And while Barbie didn't literally choose

Charlotte, the designer certainly imposed her taste upon the doll. More significantly, the doll, to whom children looked up,

was a sort of mentor to them. Just as

Sex and the

Single Girl

spread Brown's gospel to adult women, Barbie and her paraphernalia conveyed it to their younger sisters.

In Brown's protofeminist philosophy, preoccupation with appearance was a pragmatic necessity, not a narcissistic luxury. Men

desired a single woman because she had "time and often more money to spend on herself . . . the extra twenty minutes to exercise

every day, an hour to make-up her face for their date." Brown's Single Girl did not live in the world of ideas, where a looker

like Robert Browning would fall for a lump like Elizabeth Barrett; she lived in the material world, where beauty was the decisive

weapon in the everlasting battle for men. The Single Girl was not an intellectual; introspection, Brown makes clear, was a

waste of energy. But the Girl was encouraged to have a sort of cunning—a nonverbal sagacity; she expressed herself through

a vocabulary of objects rather than words.

"Men survey women before treating them," John Berger wrote in

Ways of

Seeing.

"Consequently, how a woman appears to a man can determine how she will be treated. To acquire some control over the process,

women must contain it and interiorize it." A woman must cultivate the habit of simultaneously acting and watching herself

act; she must split herself into two selves: the observer and the observed. She must turn herself, Berger says, into an "object

of vision."

Brown's book taught women how to turn themselves into such an object.

Sex and the Single Girl

is a Berlitz phrase book to the vernacular of clothing and style, a guide to help women manipulate men by manipulating how

they appear to men.

For some girls, Barbie no doubt functioned that way too. Not for all, but for many, I suspect. The relationship of the observed

self to the observing self is much like that of a Barbie doll to its owner. When a girl projects herself onto a doll, she

learns to split in two. She learns to manipulate an image of herself outside of herself. She learns what Brown and Berger

would consider a survival skill.

Another developing feminist who understood the importance of a woman's appearance was Gloria Steinem. In 1963, the Viking

Press published

The

Beach Book,

her massive volume devoted not to gender inequalities but to looking good in a bathing suit. "Nothing is as transient, useless,

or completely desirable as a suntan," she observed. "What a tan will do is make you look good, and that justifies anything."

Steinem, whose dust-jacket profile reveals that her "formative years were spent almost entirely in bathing suits," seems to

have been in a particularly Barbie-esque stage of evolution in 1963. Decades before Jane Fonda, Maria Maples, and Barbie made

exercise videos, Steinem prescribed a workout for her female readers—twenty arm pulls daily, executed while chanting: "I must

. . . I must . . . I must develop my . . . Bust." The purpose of this regimen is revealed three pages later, in a diagram

that teaches the reader how to "build" a bikini.

I doubt, however, that some of her exercises would pass muster with fitness experts. This one is particularly suspect: "Suck

against the heel of your hand. This makes thin lips full, full lips firm, and fat cheeks lean."

Steinem had less need of arm pulls than many women. That was another thing she had in common with Barbie: her looks were good

enough to land her a job as a

Playboy

Bunny. After weeks of wobbling around on spike heels, stuffing her bra with dry cleaner bags, and having her cottontail yanked

by customers, she penned a behind-the-scenes expose for

Show

magazine on the sordid, brutalizing, anything-but-glamorous working conditions at the Hefner hutch.

Significantly, Steinem's article, as Marcia Cohen has noted in

The

Sisterhood: The True Story of the Women Who Changed the World,

"made the point that

Playboy

Bunnies were exploited, though it did not make the point that they were exploited because they were women"—an oversight Steinem

acknowledges. "It was interesting," Steinem told Cohen, "that I could understand that much and still not make the connection."

Perhaps it was difficult for a woman whose looks had opened doors to realize that there were problems to having them opened

that way.

The Beach

Book

has an introduction by economist John Kenneth Galbraith, whom Gloria met in the Hamptons and who was captivated by her "terrific

good looks." "If Gloria says it's otherwise," Galbraith told Cohen, "she's wrong." Galbraith's remarks make me think of

Barbie's New York Summer,

a young adult novel with Barbie as a character that Random House published in 1962. In it, Barbie's clever writing earns her

a job at a magazine; she goes to Manhattan and is fawned over by rich, powerful men. "There are many chic women in New York,"

one tells her, "but . . . you are young and fresh and perfectly enchanting."

Galbraith strikes me as an apt introducer for

The Beach Book,

which is in large part about economics. The young Gloria—like the newly minted Barbie—was not unfamiliar with defining a lifestyle

through things. She explains how one can change roles by changing outfits, very much the way Barbie does. Some beach looks

include the "Ivy League" ("Women must wear tank suits and single strands of pearls"), "Muscle Beach" ("Alternate the coconut

oil with the application of mascara . . . Chew gum"), and "Pure Science" (Carry "moss-filled Mason jars, a notebook, and a

long-handled net"). If you're not going to wear high-status garments, though, you'd better be able to pass for a model; the

Pure Science look "works only if you are very beautiful."

Steinem's book not only catalogues the status value attached to objects, it offers suggestions for condescending to the less

fortunate. This seems odd for a woman who claims to have grown up in poverty. "One gets the sense talking to Gloria that she

was born in the Toledo equivalent of the manger," Leonard Levitt once wrote in

Esquire.

But she has thought a great deal about the class implications of sun-altered skin tone and offers this hope to those who cannot

tan: "With every office clerk able to afford a vacation at the shore, you may be able to make white skin worth more in status

than a tan."

Well versed in the art of sunbathing, Barbie, in 1963, had not yet had her feminist consciousness raised—though, like Steinem's

political awareness, it would evolve with time. ("Feminism didn't come into my life at all until 1968 or 1969," Steinem told

me when I asked her about

The Beach Book.)

In Barbie's defense, however, she could hardly have pondered the condition of "women," having been for four years the only

adult female doll on the market. This, however, changed when Mattel introduced her so-called best friend Midge.

Freckled of face, bulging of eye, Midge was from the outset a sorry Avis to Barbie's Hertz. Her debut commercial was a catalogue

of tortures endured by homely teenage girls. Midge, the ad alleged, "is thrilled with Barbie's career as a teenage fashion

model." But anyone who has ever been sixteen and female knows she was probably rent with feelings of inferiority.

"Barbie has introduced Midge to her boyfriend," the ad continues, "and the three of them go everywhere together." Terrific.

Tagging along after Mr. and Miss High School. If plastic dolls could kill themselves, I'm sure Midge would have tried.

The following year things grew slightly more equitable; Mattel gave Midge a boyfriend (Allan) and dumped a younger sister

(Skipper) on Barbie. Mattel's engineers also did something really hideous to Barbie's face, replacing her painted eyes with

feline-shaped mechanical things that blinked. Now called "Miss Barbie," she looked like the offspring of an interspecies union,

a cousin of Nastassia Kinski in

Cat People.

Not surprisingly, as Barbie racked up other doll friends she also gathered competitors. Rival toymakers could scarcely witness

Mattel's triumph without hatching plots to exploit it. Barbie's major challengers were Tammy, brought out by the Ideal Toy

& Novelty Corporation in 1962, Tressy, brought out by the American Character Doll Company in 1963, and the Littlechap Family,

introduced by Remco in 1964.

Named for an insipid movie character portrayed by Debbie Reynolds, Tammy looked as if she could have given Barbie a run for

her money; but in hindsight it's clear that she never had a chance. Barbie may have appeared as if she belonged in the fifties,

but her ethos was pure sixties; she was a swinging single with a house, a boyfriend, and no parents. Tammy, by contrast, came

with Mom and Dad. She didn't have a boyfriend, she had a brother. "Basically, Tammy was a baby doll," explains vintage Barbie

dealer Joe Blitman. Boring, sexless, and shackled to the moribund nuclear family, Tammy bit the dust in the mid-sixties when

the divorce rate took off.

I must confess to feeling chills the first time I saw Tammy. There is something creepy about a doll with the body of an eight-year-old

and the car, clothes, and trappings of a grown-up. If, as some psychoanalysts contend, anorexia is a perverse strategy to

thwart the development of female secondary sex characteristics, Tammy is the model for such a weird infant-adult. At least

Barbie embraced womanhood, however cartoonish her interpretation; she wasn't a female Peter Pan demanding car keys and the

right to vote while shirking the burden of sexual development.

Tressy was possibly even more physically bizarre than Tammy; she had a tuft of hair in the middle of her head that could be

yanked out and screwed back in, like a tape measure. When beehive hairdos went the way of the Hula Hoop, so did Tressy.

Like Tammy, Remco's Littlechap Family was cursed by its links to what

McCalVs

in 1954 termed the "togetherness" movement, in which, as Betty Friedan put it in

The Feminine Mystique,

a woman "exists only for and through her husband and children." Daughter Judy Littlechap bore a striking resemblance to Jacqueline

Bouvier Kennedy, which, when the doll was on the drawing board, no doubt seemed like a good idea. When it was released, however,

after JFK's assassination, the doll's looks worked against it; they were a ghoulish reminder of a national tragedy.

Barbie's thorniest competitor in the sixties may have been Louis Marx &Co.'s Miss Seventeen—not because she was captivating,

but because she didn't fight fair. Smarting from the Handlers' ascension, Marx dug out Barbie's Teutonic origins, acquired

rights to the Lilli doll, rechristened it Miss Seventeen and launched it in America. Then on March 24, 1961, Marx's lawyers

marched into U.S. District Court in Los Angeles and slapped Mattel with a patent-infringement suit.

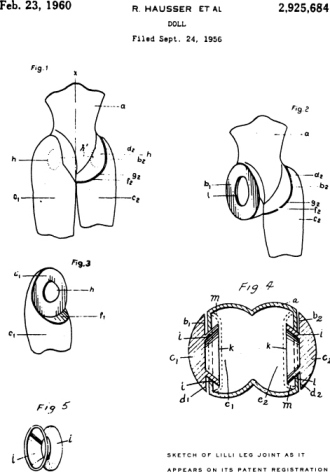

At issue was Letters Patent No. 2,925,684, which Miss Seventeen wore boldly etched on her backside. It referred to a leg joint

that permitted the doll to sit down with its legs together instead of spread apart—a useful feature, for taste reasons, on

a sexy adult doll.

Given Marx's reputation for getting rich off cheap versions of stolen ideas, Miss Seventeen was the quintessential Marx product.

If Barbie was tawdry, Miss Seventeen was downright mangy; as slutty as Lilli, but not nearly so healthy. Her plastic was jaundiced,

and she seemed in need of a square meal—not because she was too thin but because she suffered from vitamin deficiencies. Her

hair emerged from her head in irregular clumps; and while neither she nor Barbie could be said to have a penetrating gaze,

her eyes were markedly out of focus, as if bleary from drugs. Miss Seventeen could easily pass for Miss Teen Runaway; if she

were a person, she'd probably never make it to Miss Eighteen.

Marx alleged that Mattel had copied the "form, posture, facial expression and novel overall . . . appearance" of the

Bild

Lilli doll and "led the doll field and purchasing public to the belief that said 'Barbie' dolls were an original product .

. . thereby perpetrating a fraud and a hoax upon the public."