Forever Barbie (11 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

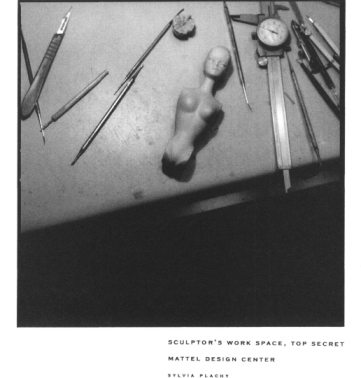

Even if it wanted to, Mattel could not assert ignorance of pagan symbolism. This isn't merely because Aldo Favilli, the Italian-born,

classically educated former sculpture restorer at Florence's Uffizi Gallery who has run Mattel's sculpture department since

1972, ought to know a thing or two about iconography. In 1979, the company test-marketed two "Guardian Goddesses," "SunSpell,"

"the fiery guardian of good," and "MoonMystic," "who wears the symbols of night." Identical in size and shape to Barbie, they

came with four additional outfits--"Lion Queen," "Soaring Eagle," "Blazing Fire," and "Ice Empress"--sort of Joseph Campbell

meets Cindy Crawford. But even stranger than their appearance was what they did. To "unlock" their "powers," you

spread

their legs

-or, as their box euphemizes, made them "step to the side." Then they flung their arms upward, threw off their street clothes

and controlled nature. Freezing volcanoes, drying up floods, blowing away tornadoes, and halting a herd of stampeding elephants

are among the activities suggested on their box.

The goddesses took Barbie's crystalline hardness one step further. They wore plastic breastplates and thigh-high dominatrix

boots--outfits created by two female Mattel designers that evoke Camille Paglia's characterization of the Great Mother as

"a sexual dictator, symbolically impenetrable." Yet despite their literal virginity, their powers were metaphorically linked

to sex. To set the dolls' mechanism, their thighs had to be squeezed together until they clicked. To release it, their legs

had to be parted; the box features a drawing of two juvenile hands clutching each foot. Vintage doll dealers speculate that

the goddesses were removed from the market because their mechanism was too delicate. But between their lubricious leg action

and pantheistic message, they strike me as having been too indelicate.

IF I HAD TO LOCATE THE POINT AT WHICH I BEGAN TO SEE the ancient archetype within the modern toy, it would be at the home

of Robin Swicord, a Santa Monica-based screenwriter whom Mattel commissioned in the 1980s to write the book for a Broadway

musical about the doll.

Swicord is not a New Age nut; she's a writer. And even after mega-wrangles with Mattel's management—the musical was sketched

out but never produced—she is still a fan of the doll. "Barbie," she said, "is bigger than all those executives. She has lasted

through many regimes. She's lasted through neglect. She's survived the feminist backlash. In countries where they don't even

sell makeup or have anything like our dating rituals, they play with Barbie. Barbie embodies not a cultural view of femininity

but the essence of woman."

Over the course of two interviews with Swicord, her young daughters played with their Barbies. I watched one wrap her tiny

fist around the doll's legs and move it forward by hopping. It looked as if she were plunging the doll into the earth—or,

in any event, into the bedroom floor. And while I handle words like "empowering" with tongs, it's a good description of her

daughters' Barbie play. The girls do not live in a matriarchal household. Their father, Swicord's husband, Nicholas Kazan,

who wrote the screenplay for

Reversal of Fortune,

is very much a presence in their lives. Still, the girls play in a female-run universe, where women are queens and men are

drones. The ratio of Barbies to Kens is about eight to one. Barbie works, drives, owns the house, and occasionally exploits

Ken for sex. But even that is infrequent: In one scenario, Ken was so inconsequential that the girls made him a valet parking

attendant. His entire role was to bring the cars around for the Barbies.

In other informal interviews with children, I began to notice a pattern: Clever kids are unpredictable; they don't cut their

creativity to fit the fashions of Mattel. One girl who wanted to be a doctor didn't demand a toy hospital; she turned Barbie's

hot pink kitchen into an operating room. Others made furniture—sometimes whole apartment complexes—out of Kleenex boxes and

packing cartons. And one summer afternoon in Amagansett, New York, I watched a girl and her older brother act out a fairy

tale that fractured gender conventions. While hiking in the mountains, a group of ineffectual Kens was abducted by an evil

dragon who ate all but one. He remained trapped until a posse of half-naked Barbies—knights in shining spandex—swaggered across

the lawn and bludgeoned the dragon to death with their hairbrushes.

When the dragon devoured the Kens, the brother dismembered them. "More boys would buy Barbies if you could put them together

yourself," he told me, adding that he enjoys combining the body parts in original ways. "That was the beginning of the downfall

of Barbie in our house," his mother told me. "Once we saw one with three legs and two heads, it was hard to just let her be

herself."

I also learned to ask children what their doll scenarios meant to them, rather than to make assumptions. Last summer, for

example, I was playing on my living-room floor with a six-year-old, under the watchful eye of her parents—he a black television

executive, she a white magazine writer. The girl had brought her own blond Barbie, and the doll—like the girl—was quite a

coquette. Her "play" consisted of going on dates with five of my male dolls: a blond Ken, a G.I. Joe, and three members of

Hasbro's Barbie-scaled New Kids on the Block. She completely ignored Jamal, a black male doll made by Mattel, leaving him

sprawled facedown on the rug—troublingly evocative of William Holden at the beginning of

Sunset Boulevard.

I was not, it soon became evident, the only one who was troubled. When Jamal had been neglected for what seemed like eons,

the girl's mother finally grabbed him and asked, "Wouldn't Barbie like to go out with Jamal?" The child looked exasperated.

"But she can't, Mommy," she said. "That's

Daddy."

Scholars agree that for children, "play" is "work." Jean Piaget has grouped children's play into three categories: games of

mastery (building with blocks, climbing on jungle gyms), games with rules (checkers, hide-and-seek), and games of "make-believe,"

in which play involves a story that begins "What if. . ." Make-believe play is concerned with the manipulation of symbols

and the exercise of imagination—and it is into this category that Barbie play falls.

To some scholars, toys and games are the Lego bricks in the social construction of gender. "When kids maneuver to form same-gender

groups on the playground or organize a kickball game as 'boys-against-the-girls,' they produce a sense of gender as dichotomy

and opposition," University of Southern California sociologist Barrie Thorne writes in

Gender Play.

"And when girls and boys work cooperatively on a classroom project, they actively undermine a sense of gender as opposition."

But the role of make-believe play is less clear than that of games of mastery or games with rules because it involves entering

the logic (and occasionally illogic) of the child's imaginary world. Children sometimes use Barbie and Ken to dramatize relationships

between the adults in their lives, especially if those adults are a source of anxiety. In Sarah Gilbert's novel

Summer Gloves,

the female narrator's daughter mutilates her Midge doll and practically glues her Ken to her Barbie. This seems odd until

the mother comments: "I married a Ken and he's about to run off with a Midge. And they may good and well deserve each other,

the bores."

Children's therapists even use Barbie and Ken—or the Heart family, Mattel's Barbie-sized domestic unit—to help their young

patients communicate. "A lot of them act out their own problems with the Heart family," Yale University psychologist Dorothy

G. Singer told me. "One child whose parents were going to be divorced would constantly lock Mr. Heart out of the dollhouse—make

him sleep in the garden."

Singer is the author of

Playing for Their Lives: Helping Troubled Children

Through Play Therapy,

and, with her husband, Yale psychologist Jerome L. Singer, of

Make Believe: Games and Activities to Foster Imaginative Play in

Young Children.

She says that although some children use Barbie for creative play, it's not because the doll has—as Mattel's commercials contend—

"something special." "Imaginative kids take some toys and make them into anything they want," she told me. "But you have to

ask: Where does that imagination come from and how does it start? What we found in our research is that if the parent sanctions

that kind of play—starts a game, helps—then by the time the child is four or five, [he or she] doesn't need the parent. They

now have ideas for scripts and they can make any world that they want."

Not every parent is quite so willing to disappear. In her short story "The Geometry of Soap Bubbles," Rebecca Goldstein dramatizes

the efforts of a mother—Chloe, a member of the classics department at Barnard College— to teach the art of make-believe to

her daughter, Phoebe. In defiance of her colleagues' "finer sensibilities," Chloe presents the child with an array of Kens

and Barbies, "having felt the drama latent in their flesh." Then she uses the dolls to act out mythological tales. In one

scenario, Ken, "clad in psychedelic bathing trunks," becomes "the shining god Apollo"; Barbie, the clairvoyant princess Cassandra.

In another, a corybantic adaptation of Euripides's

Bacchae,

Ken portrays Dionysus. Unfortunately, Chloe's strategy works too well: Instead of playing with the dolls, the daughter, who

prefers math problems, asks her mother to play with them

'for

her."

Even when mothers don't intervene actively, they can influence what their children do with the doll. During her daughter's

Barbie years, Ann Lewis, Democratic party activist and sister of Massachusetts Representative Barney Frank, spent her nights

doing political work. One evening, before going out, she noticed that her daughter had dressed Barbie in a floor-length formal

gown. "Where's Barbie going?" Lewis asked. "To a meeting," her daughter replied.

This is not to say that when daughters emulate their mothers in Barbie play, it's always a constructive experience. Mothers

who believe in restricted roles for women transmit messages of restriction: of opportunities, behavior, even body size. "There

are a lot of mothers who don't want their kids to be fat when they go to the country club and put on bathing suits," Singer

told me. "I have in my own practice now a child whose mother is forcing her to diet. She goes to Weight Watchers for Children

. . . and this kid eats this crazy stuff. She's a little plump but not in any way overweight or looking obese."

Sometimes mothers blame Barbie for negative messages that they themselves convey, and that involve their own ambivalent feelings

about femininity. When Mattel publicist Donna Gibbs invited me to sit in on a market research session, I realized just how

often Barbie becomes a scapegoat for things mothers actually communicate. I was sitting in a dark room behind a one-way mirror

with Gibbs and Alan Fine, Mattel's Brooklyn-born senior vice president for research. On the other side were four girls and

an assortment of Barbie products. Three of the girls were cheery moppets who immediately lunged for the dolls; the fourth,

a sullen, asocial girl, played alone with Barbie's horses. All went smoothly until Barbie decided to go for a drive with Ken,

and two of the girls placed Barbie behind the wheel of her car. This enraged the third girl, who yanked Barbie out of the

driver's seat and inserted Ken. "My mommy says men are supposed to drive!" she shouted.

Her two playmates looked stunned. Fine and Gibbs looked stunned. Even the girl with the horses looked stunned. Fine finally

shrugged his shoulders and said: "And they blame it on

us?"

A

s a feat of engineering, the 1967 Twist 'N Turn Barbie is a marvel. Steve Lewis and Jack Ryan devised a doll that swiveled

on a compound angle at its hips and neck. A compound angle is not perpendicular to the vertical axis of the doll; it is askew,

and the resulting tilt gives the doll a human-looking

contrapposto.

A delicate new face with eyelashes made of real synthetic hair added the final touch. Lewis remembered the meeting at which

he unveiled the prototype: "Everyone sat back and there was great silence. And one of the VPs, who is still in the toy business

but not with Mattel, said, 'That is the most beautiful doll I have ever seen.' "

The doll's promotion was less attractive, however. In the Twist 'N Turn kickoff commercial, a swarm of girls stampeded to

a toy store to trade in their old Barbies for a discount on the new one. So much for projecting a personality onto a beloved

anthropomorphic toy, so much for clinging to Barbie as a transitional object, or, as in the case of the toy in Margery Williams's

The Velveteen Rabbit,

cherishing Barbie because she had been "made real" through wear.

Futurist Alvin Toffler condemned the trade-in as proof that "man's relationships with things are increasingly temporal." But

he missed what was, for women, a more alarming message. It wasn't worn sneakers or crushed Dixie cups that the kids were throwing

away; it was women's bodies. Older females should simply be chucked, the ad implied, the way Jack Ryan discarded his older

wives and mistresses. Ryan, inventor of the Hot Wheels miniature car line that Mattel would introduce the following year,

brought automotive obsolescence to Barbie.

In 1968, Mattel plunged Barbie deeper into social irrelevance. It gave her a voice—so she could declare her membership in

the Silent Majority. "Would you like to go shopping?" the doll twittered. "I love being a fashion model. What shall I wear

to the prom?" This may be what Tricia Nixon said when you pulled the loop at the back of her neck, but in my experience a

young woman in 1968 had broader concerns.

In a world where the under-thirties had pitted themselves against the over-thirties, Barbie betrayed her peers. She had a

passing familiarity with youthspeak—"groovy" modified an occasional outfit or product—but no affinity with youth culture.

Barbie existed to consume at a time when young people were repudiating consumption. They moved to communes and wore lumpy,

distressed work clothes. Synthetic materials fell into disrepute, and Barbie's very essence—not to mention her house, beach

bus, sister, and boyfriend—was plastic. For Barbie to have endorsed the values of the young would have been to negate herself.

Between 1970 and 1971, the feminist movement made significant strides. In 1970, the Equal Rights Amendment was forced out

of the House Judiciary Committee, where it had been stuck since 1948; the following year, it passed in the House of Representatives.

In response to a sit-in led by Susan Brownmiller,

Ladies' Home Journal

published a feminist supplement on issues of concern to women.

Time

featured

Sexual Politics

author Kate Millett on its cover, and

Ms.,

a feminist monthly, debuted as an insert in

New York

magazine. Even twelve members of a group with which Barbie had much in common—Transworld Airlines stewardesses—rose up, filing

a multimillion-dollar sex discrimination suit against the airline.

Surprisingly, Barbie didn't ignore these events as she had the Vietnam War; she responded. Her 1970 "Living" incarnation had

jointed ankles, permitting her feet to flatten out. If one views the doll as a stylized fertility icon, Barbie's arched feet

are a source of strength; but if one views her as a literal representation of a modern woman—an equally valid interpretation—

her arched feet are a hindrance. Historically, men have hobbled women to prevent them from running away. Women of Old China

had their feet bound in childhood; Arab women wore sandals on stilts; Palestinian women were secured at the ankles with chains

to which bells were attached; Japanese women were wound up in heavy kimonos; and Western women were hampered by long, restrictive

skirts and precarious heels.

Given this precedent, Barbie's flattened feet were revolutionary. Mattel did not, however, promote them that way. Her feet

were just one more "poseable" element of her "poseable" body. It was almost poignant. Barbie was at last able to march with

her sisters; but her sisters misunderstood her and pushed her away.

Celebrities who in the sixties had led Barbie-esque lives now forswore them. Jane Fonda no longer vamped through the galaxy

as "Barbarella," she flew to Hanoi. Gloria Steinem no longer wrote "The Passionate Shopper" column for

New York,

she edited

Ms.

And although

McCalVs

had described Steinem as "a life-size counter-culture Barbie doll" in a 1971 profile, Barbie was the enemy.

NOW's formal assault on Mattel began in August 1971, when its New York chapter issued a press release condemning ten companies

for sexist advertising. Mattel's ad, which showed boys playing with educational toys and girls with dolls, seems tame when

compared with those of the other transgressors. Crisco, for instance, sold its oil by depicting a woman quaking in fear because

her husband hated her salad dressing. Chrysler showed a marriage-minded mom urging her daughter to conceal from the boys how

much she knew about cars. And Amelia Earhart Luggage—if ever a product was misnamed—ran a print ad of a naked woman painted

with stripes to match her suitcases.

Feminists followed up in February 1972 by leafleting at Toy Fair. They alleged that dolls like Topper Toy's Dawn, Ideal's

Bizzie Lizzie, and Mattel's Barbie encouraged girls "to see themselves solely as mannequins, sex objects or housekeepers,"

reported

The New York Times.

The first two dolls were perhaps deserving targets. Dawn's glitzy lifestyle was devoid of social responsibility, a precursor,

as collector Beauregard Houston-Montgomery has put it, of the "disco consciousness of the 1970s." And Bizzie Lizzie, who clutched

an iron in one hand and a mop in the other, was a drudge. But if feminists had embraced Barbie when she stepped down from

her high heels, her seventies persona might have been dramatically different. She was on the brink of a conversion. If they

hadn't spurned, slapped, and mocked her, she might have canvassed for George McGovern or worked for the ERA. She might have

spearheaded a consciousness-raising group with Francie and Christie, or Dawn and Bizzie Lizzie. But Barbie could not go where

she was not wanted. "Living" Barbie lasted only a year. She went back on tiptoe and stayed there.

Perhaps because of this bitter legacy, "feminist" seems to be an obscene word at Mattel. "If you asked me to give you fifty

words that describe me, it wouldn't be on the list," said Rita Rao, executive vice president of marketing on the Barbie line.

Yet when Rao discusses her career, she recounts experiences that might have made another woman join NOW, like her 1964 job

interview at Levi Strauss where she was told, "We don't hire women"; and in 1969, her applications to various stock brokerage

firms that, except for one to Dean Witter, were turned down for the same reason.

First hired in 1966, Rao left Mattel in 1970, returned in 1973, left again in 1979 to start her own company, and returned

in 1987 as a vice president. Mattel must be a good place for a woman to work, she jokes, because she keeps coming back. "I

know Ruth Handler absolutely doesn't think of herself as a feminist," Rao explains. "She's antifeminist, if anything. [But]

when there's a woman at the top, it's illogical to say that a woman can't be capable. So even though she didn't really promote

women or move them forward, her very being there made a statement."

Ruth Handler is almost too original for modifiers like "feminist" and "antifeminist" or even "good" and "evil." "Swashbuckling,"

"intrepid," "one-of-a-kind"—these are adjectives for Ruth. Conventional propriety has never seemed to weigh heavily upon her.

It isn't so much that she sees herself outside the law, but that she is a law unto herself. This no doubt helped her to cope

with breast cancer; unashamed, she diagnosed the shortcomings of existing mastectomy prostheses and founded a company to make

better ones. But it may also have contributed to her being found guilty of white-collar crimes that, in the words of the judge

who sentenced her, were "exploitative, parasitic, and . . . disgraceful to anything decent in this society."

Barbie's fate in the early seventies was very closely linked with Ruth's. Barbie's values were Ruth's values, and the risk

Ruth took by introducing Barbie had paid off handsomely. But in 1970, Ruth's luck changed. "I had a mastectomy and the world

started to fall apart," she said.

Back at work two weeks after the operation, Ruth had her hands full. While Elliot handled Mattel's creative side, Ruth attended

to its business and financial aspects, which, ten years after the company went public, had expanded well beyond toys. In 1969,

Mattel acquired Metaframe Corporation, a manufacturer of hamster cages, aquariums, and other pet supplies. Not satisfied with

small animals, in 1970 it moved to larger ones—lions, tigers, and bears—by acquiring the Ringling Bros, and Bamum & Bailey

Circus. It bought Audio Magnetics Corporation, a manufacturer of audiotape, and Turco Manufacturing, a maker of playground

equipment, and it formed Optigon Corporation, a distributor of keyboard musical instruments.

It even got into the movie business, forming Radnitz/Mattel Productions, Inc., which produced the Academy Award-winning

Sounder.

Mattel's goal in diversifying was to retain some sort of equilibrium. Toys are a volatile, seasonal business; by acquiring

stable companies with stable sales, Mattel hoped to offset the capriciousness of the toy market. It also began accounting

practices that would even out its earnings vacillations, such as "annualization," the deferring of some of its expenses until

late in the year when most of its sales took place. Before beginning its diversification, it brought in two key outsiders:

Arthur Spear, an MIT engineering graduate who had headed manufacturing operations at Revlon; and Seymour Rosenberg, a financial

expert who had earned a reputation as an acquisitions wizard at Litton Industries.

Despite all this, 1970 was as bad a year for Mattel as it was for Ruth. Its Talking Barbies were silenced when its plant in

Mexicali, Mexico, where they were made, burned. And when its Sizzler toy line—a subsidiary of Hot Wheels—failed to generate

as much revenue as Mattel had predicted, the company simply overstated its sales, net income, and accounts receivable, and

instigated a "bill and hold" accounting practice—invoicing clients for orders that, because the clients had the right to cancel

and often did, were not shipped. The inclusion of these "bill and hold" sales increased reported pretax earnings by about

$7.8 million. Had Mattel made a miraculous recovery—which, given the unpredictability of the industry, was not impossible—its

borrowing against future sales might have gone unnoticed. But as the company weathered bad quarter after bad quarter, the

gap between the business it reported and the business it did widened.

By 1972, it could no longer disguise its losses. It reported a $29.9 million loss on sales of $272.4 million; and Wall Street,

which had embraced Mattel as a glamour stock, began to suspect that something was rotten in Hawthorne. In August, Seymour

Rosenberg, executive vice president, left; his acquisitions had been losers and his accounting practices were getting Ruth

into hot water. Meanwhile, Mattel's bankers, worried about their short-term financing, had been having independent discussions

with operations manager Arthur Spear. In December, they refused to deal with Ruth any longer; she was permitted to retain

the title of president, but forced to relinquish control of the company to Spear.

In February 1973, Mattel's internal drama became public farce. The company issued contradictory press releases within three

weeks. The first predicted a strong recovery; the second said: Forget the first; we just happened to have overlooked a $32.4

million loss. When, as a consequence of the announcement, Mattel stock plummeted, its shareholders filed five class-action

lawsuits against the company, various current and former officers, and Arthur Andersen & Co., its independent accounting agency.

The Securities and Exchange Commission also began an investigation.

Ruth, forced to resign as president (but allowed to continue with Elliot as cochairman of the board), was publicly repudiated,

stripped of her power. Shaken, she lost faith even in Barbie.

"There's a group of people in this company that says Barbie is dead," former Mattel executive Tom Kalinske recalls Ruth telling

him in 1973. "Last year we had our first decline ever since the introduction of Barbie. People are saying that Barbie's over,

finished, and that we ought to get on to other categories of toys." Shocked, Kalinske responded, "That's the most ridiculous

thing I've heard. Barbie's going to be here long after you and I are gone." Moved by his enthusiasm, Ruth made him marketing

director on the line.