Forever Barbie (14 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

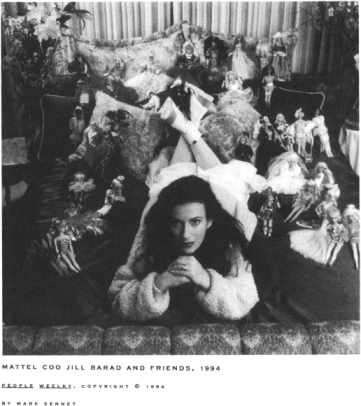

Perhaps even more than Shackelford, Jill Elikann Barad, who joined Mattel in 1981 and was made its CEO in 1992, understands

the value of appearance—and how to create a look that sells. While still an undergraduate at New York's Queens College, she

traveled around the East Coast as a beauty consultant for Love Cosmetics. A drama major who graduated in 1973, she briefly

flirted with an acting career, landing a nonspeaking part as Miss Italian America in

Barbarella

producer Dino De Laurentiis's film

Crazy Joe;

but she renounced greasepaint for Coty Cosmetics—ascending, in a record three years, from a lowly trainer of department store

demonstrators to brand manager of its entire line. Nor did marriage to Paramount executive Thomas Barad detour her rise. When

she relocated to Los Angeles in 1978, the Wells, Rich, Greene ad agency put her in charge of its Max Factor account. Even

her application to Mattel—made after taking time off to have a baby—stressed her beauty know-how: she approached the company

with a plan to sell cosmetics to children.

Barad was not, however, permitted to realize her vision immediately. Slime was still an important product at Mattel, and Barad's

first assignment was to sell it in its then-current incarnation, A Bad Case of Worms, which featured, besides the popular

green glop, brown vinyl crawlers. The modified Slime also functioned as an activity toy. If you threw it against a wall, it

would stick and wriggle down. Barad rose to the occasion but ultimately confronted her boss, Tom Kalinske, and asked for greater

responsibility on an aspect of girls' toys. He assigned her to work with Shackelford on Barbie. While she was pregnant with

her second child she was promoted to marketing director, and what can be described as the doll's golden era began.

A chief element in positioning the new Barbie was her promotion. In 1984, after a campaign that featured "Hey There, Barbie

Girl" sung to the tune of "Georgy Girl," Mattel launched a startling series of ads that toyed with female empowerment. Its

slogan was "We Girls Can Do Anything," and its launch commercial, driven by an irresistibly upbeat soundtrack, was a sort

of feminist

Chariots of Fire.

Responding to the increased number of women with jobs, the ad opens at the end of a workday with a little girl rushing to

meet her business-suited mother and carrying her mother's briefcase into the house. A female voice says, "You know it, and

so does your little girl." Then a chorus sings, "We girls can do anything."

The ad plays with the possibility of unconventional gender roles. A rough-looking Little Leaguer of uncertain gender swaggers

onscreen. She yanks off her baseball cap, her long hair tumbles down, and—sigh of relief—she grabs a particularly frilly Barbie

doll. (The message: Barbie is an amulet to prevent athletic girls from growing up into hulking, masculine women.) There are

images of gymnasts executing complicated stunts and a toddler learning to tie her shoelaces. (The message: Even seemingly

minor achievements are still achievements.) But the shot with the most radical message takes place in a laboratory where a

frizzy-haired, myopic brunette peers into a microscope. Since the seventies, Barbie commercials had featured little girls

of different races and hair colors, but they were always pretty. Of her days in acting school, Tracy Ullman remarked in

TV Guide

that she was the "ugly kid with the brown hair and the big nose who didn't get [cast in] the Barbie commercials." With "We

Girls," however, Barbie extends her tiny hand to bookish ugly ducklings; no longer a snooty sorority rush chairman, she is

"big-tent" Barbie.

Although the ad, and, by extension, the whole career Barbie series, is not without problematic and contradictory content,

it is such a departure from the doll's fatuous, disco positioning in the seventies that one's jaw tends to drop. And one wonders:

How on earth did it happen?

One factor was the Barbie group at Ogilvy & Mather, the ad agency that had, in the seventies, acquired Carson/Roberts. By

1984—a year after Sally Ride's landmark space flight, the same year as Geraldine Ferraro's historic bid for the U.S. vice

presidency—Mattel urged O&M creative director Elaine Haller and writer Barbara Lui to, in Lui's words, "express where women

were and where they wanted their daughters to be at the time." Upon hearing that, Lui told me last year, she remembered her

own childhood on Manhattan's Upper West Side. "My mother's words came to me," she said. "My name is Barbara—I was called Bobbie

at home—and my mother used to say, 'Bobbie, you can do anything,' " which, with a few revisions, became the doll's new slogan:

"We girls can do anything, right, Barbie?"

And in 1985, it seemed "we girls" actually could. For the first time since the sixties, Barbie, in her Day-to-Night incarnation,

was positioned

as

a career woman

by

career women who knew what it took to achieve in the business world. (Not in an idealized world, but in the one that really

existed.)

What they came up with was Day-to-Night Barbie, a yuppie princess, equipped to charge, network, and follow the market. Her

attache case contains a credit card, a business card, a newspaper, and a calculator. Although her suit is baby-blanket pink

rather than boardroom blue, it is tastefully cut and covers her knees. Her outfit, however, does more than look good during

the day. Turn it inside out, and it is a fussy, glittery evening dress.

To decode the meaning of Day-to-Night Barbie, one must turn to the work of Joan Riviere, a female Freudian psychoanalyst,

who in 1929 published an essay about a pattern she had begun to notice among her professionally accomplished female analysands.

Many powerful women, Riviere discovered, were uncomfortable with their masculine strivings; to conceal them, they overcompensated,

decking themselves out like caricatures of women. One woman, after giving a successful lecture, flirted idiotically and inappropriately;

she also delivered her presentation in cartoonishly feminine clothes. Others exaggerated different aspects of femininity,

and one even dreamt that she had been saved from a precipitous fall by wearing a mask. "Womanliness therefore could be assumed

and worn as a mask," Riviere wrote, "both to hide the possession of masculinity and to avert the reprisals expected if [a

woman] was found to possess it—much as a thief will turn out his pockets and ask to be searched to prove he has not the stolen

goods."

In her book

Female Perversions: The Temptations of Emma Bovary,

psychoanalyst Louise J. Kaplan uses the term

homeovestism

for this strategy of cloaking one's cross-gender strivings by disguising oneself as a parody of one's own sex. It is the reverse

of transvestism, in which one acts out one's cross-gender impulses by wearing the clothes of the opposite sex. Nor is homeovestism

practiced exclusively by women. A male homeovestite, for instance, might mask his feminine urges by dressing up like Norman

Schwarzkopf. In literature, Scarlett O'Hara seems a convincing example of a female homeovestite. She is as aggressive and

tenacious as any biological male, but she conceals it behind fluttering eyelashes and an affected fragility. Of course, the

only people who know they are homeovestites are the homeovestites themselves. It is, I suppose, possible for a woman to tart

up like a Gabor sister and not know she is a caricature. But if a high-powered female executive wears enough makeup for a

Kabuki performance, negotiates in a purr, tosses her hair coquettishly, unbuttons more than two buttons on her clinging silk

blouse, and generally vamps around the conference table, she may well be a homeovestite.

Day-to-Night Barbie strikes me as a teaching implement for homeovestism. Clearly, the doll is meant to be a serious professional;

her case contains the tools for executive achievement, where the idea of possessing a "tool," a colloquialism for the penis,

implies a sort of phallic empowerment. Her nighttime outfit, however, is about hiding those "tools." Like the thief who turns

out his pockets, the doll disguises herself by exposing herself. Her shoulders are bare; her toes are uncovered; her translucent

skirt flutters around her legs. She is fluffy, girlish, vulnerable. By day, a virago; by night, Little Bo Peep.

Mattel issued Day-to-Night ensembles for other vocations as well. By rearranging her costume, any female achiever—teacher,

dress designer, TV news reporter—can masquerade as Maria Maples or Donna Rice. Ken also has a Day-to-Night incarnation, but

his seems to reflect cross-class rather than cross-gender strivings. By day, a TV sports reporter; by night, a Wayne Newton

impersonator.

Although Kaplan categorizes homeovestism as a "perverse strategy," it strikes me as both cynical and pragmatic. Masculine

business clothing has always been power-coded; something as subtle as the width of a pinstripe can signal an executive's status.

But for women, the coding is less easy to decipher. Whether one likes it or not, there is a strong power-pulchritude nexus

in business; making it to the top in a fashion or entertainment field involves not just the bottom line, but the hemline,

neckline, hairline, etc. Of course too much glamour can be as bad as not enough. It interferes with a woman's ability to be

taken seriously. But if one has to err, Barbie teaches, better soignee than sorry.

Barbie's 1986 astronaut incarnation certainly weighs in on the side of glamour. When Barbie first blasted off in 1965, she

wore a baggy gray spacesuit. By 1986, you wouldn't catch her in that kind of

shmatte.

She comes with a hot pink miniskirt, a clear plastic helmet, sleek pink bodysuit, even silver space lingerie. "I thought Barbie

would

dress

if she were on the moon," said Carol Spencer, the outfit's designer.

She-Ra, Princess of Power, is another Mattel toy from this period that explores the link between female strength and female

beauty. Promoted with the slogan, "The fate of the world is in the hands of one beautiful girl," She-Ra, a five-and-a-half-inch

action figure, was introduced as the sister of Mattel's He-Man in 1985, the same year as Day-to-Night Barbie. He-Man by then

required no introduction. On the market since 1982, he and his fellow Masters of the Universe, based on a popular children's

television show, were by 1984 second in sales only to Barbie.

She-Ra inhabits a world called Etheria, a curious mix of Middle Earth and Rodeo Drive. From what the catalogue terms its "plush

rug and free-standing fireplace" to its "clothes tree for shields, swords and capes," She-Ra's Crystal Castle is a sort of

Valhalla 90210, populated by sturdy, breast-plated females reminiscent of the biker Valkyries in Charles Ludlum's Wagnerian

satire,

Der Ring Gott Farblonjet.

There is a villain named Catra ("Jealous Beauty!" the catalogue calls her), a secret agent named Double Trouble (who literally

has two faces), a boyfriend named Bow, and several assorted allies including Castaspella, an "enchantress who hypnotizes."

Because of their long, combable hair and their sparkling outfits the figures were introduced as "fashion dolls," but this

group doesn't just change its clothes. Children can use the dolls to act out a struggle between females for the title of "most

powerful woman in the Universe."

Although She-Ra is not outfitted for the boardroom, the doll, perhaps even more than Day-to-Night Barbie, seems to be an instructional

tool for corporate achievement. She-Ra's state of nature is a state of perpetual war. All the inhabitants are armed, and some

of them are dangerous. Women are designated as jealous, manipulative (spell-casting), and Janus-faced. And of all the weapons

each doll possesses, perhaps the most potent is her beauty.

While She-Ra was not a flop—in the first of her two years on the market, she generated about $65 million in domestic sales—she

never approached Barbie. Some say this is because the dolls were too robust. "They looked like lady wrestlers," observed collector

Beauregard Houston-Montgomery. But I suspect She-Ra's short life was predicated on metaphor. No matter what she wears, Barbie

is a female fertility archetype. She-Ra, by contrast, lacked Barbie's pronglike feet; she and her pals could not plunge their

toes into the earth, they merely stood solidly upon it. They had no totemic link to the power of the Great Mother. Their abundant

hair and radioactive eye makeup are not enough. If Barbie is pure physical yin, they are, alas, rather yang.

Barad was inspired to create She-Ra and her world after a conversation with her sister, who had disparaged toymakers for inflicting

silly, frilly playthings on American daughters. "It seemed time to offer little girls a role model who also had strength and

power," Barad told

Working Woman

in 1990. And to play out the other early-eighties fantasy—"having it all," where "all" referred to children and a career—Barad

invented the Heart Family, a Barbie-sized couple that, unlike Barbie and Ken, were married and had a brood of plastic children.

The She-Ra state of war, however, far more than the Heart household's domesticity, reflected the atmosphere at Mattel during

the dolls' development. By 1984, CEO Arthur Spear's diversification strategy had proved disastrous. Mattel was on the brink

of bankruptcy. It had begun the year burdened by a staggering $394 million loss from the previous year. Like the executives

at Warner Communications' Atari division, Spear had been seduced by the seeming boundlessness of the home video game market.

To him, the country's craving for the likes of Pac-Man and Space Invaders looked insatiable. Inspired by Atari's gargantuan

profits—from 1979 to 1980 Atari's sales increased from $238.1 million to $512.7 million—Mattel in 1980 introduced Intellivision,

a competitor to Atari's home video system that in 1981 did, in fact, initially do well. The company's electronics division

was also at work on a line of home computers.