Forever Barbie (29 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

I

n December 1993, a platoon of bellicose Barbies mysteriously appeared on toy-store shelves in forty-three states. Their fluffy

skirts and lace-trimmed leggings were identical to those of their sister Talking Barbies, from whose microchips the nettlesome

"Math class is tough" had been newly purged. But their voices were different. "Eat lead, Cobra," they bellowed. "Vengeance

is mine!" Meanwhile, in the boy-toy ghetto of the same stores, a few "Talking Duke" characters in Hasbro's G.I. Joe line began

to exhibit acute testosterone deficiencies. "Let's go shopping," they chirped. "Wrill we ever have enough clothes?"

This outbreak of gender trouble was no accident. A group calling itself the Barbie Liberation Organization revealed that it

had surgically swapped hundreds of Barbie talk mechanisms with those of G.I. Joe. Loosely organized by a graduate student

at the University of California at San Diego, the BLO claimed to be made up of artists, professionals, and concerned parents

across the country. "One of our members is eighty-seven years old," a BLO spokesperson told me. "And she helped when we were

brainstorming the switch. She didn't have that much of a problem with the Barbies. But she is a Hungarian Jew who had nearly

all her family killed in World War Two. So she had a very strong reaction against the war toys."

Befuddled consumers brought the doctored dolls to the attention of the press, which, in the boring week between Christmas

and New Year's, lavished attention. Not enough to justify the BLO's $9,000 out-of-pocket expenses perhaps, but quite a bit.

Enough to make Mattel cross, particularly two weeks later when its big winter media event—the presentation by Jill Barad of

a $500,000 donation to the South Bronx Children's Health Center, founded by singer Paul Simon—was upstaged by natural disasters.

Part of Mattel's plan to contribute $1 million to various children's health clinics in 1994, the philanthropic photo opportunity

had been scheduled for January 18—the day after Los Angeles was hit by a major earthquake and New York City paralyzed by a

winter storm.

The BLO calls its surgery "political art," a critique of gender stereotypes in toys. Mattel calls it "product tampering,"

which, in fact, it is. The disparity between these perspectives is why the use of Barbie by artists will never be a simple

affair.

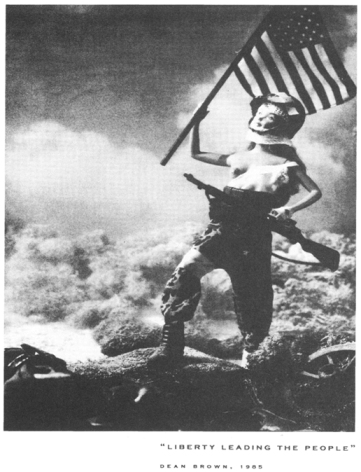

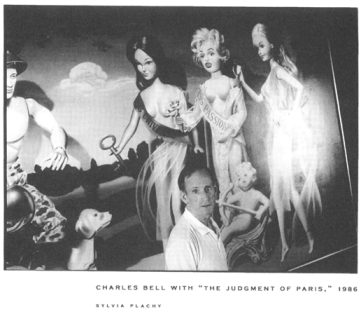

There are many doors through which one could enter a discussion of Barbie in visual art. One could begin by dropping names—mentioning

Andy Warhol's 1986 portrait of the doll or photorealist Charles Bell's wall-sized

Judgement of Paris,

also from 1986, which featured Barbie, Ken, and G.I. Joe. One might talk about how in the early eighties, photographer Ellen

Brooks used fashion dolls to comment on gender roles, and that three of those photos were included in the Whitney Museum of

American Art's 1983 Biennial. Or one could cite Scottish sculptor David Mach, who used hundreds of Barbies to critique consumer

capitalism in a piece called

Off the

Beaten Track.

Installed in 1988 at the University of California at Los Angeles's Wight Art Gallery, it involved a horde of blond, plastic

caryatids propping up a giant shipping container—literally "supporting" the consumer economy.

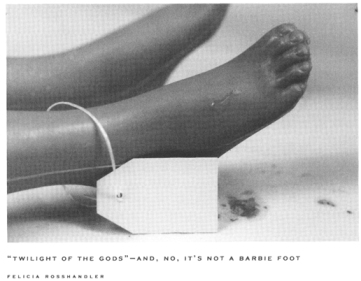

Another door would lead one through the history of doll images in art. Freud's essay on the uncanny would, of course, reappear;

one would talk about the creepiness of lifelike dolls and automata. One would mention, among others, German Surrealist Hans

Bellmer, who in the 1930s photographed parts of female mannequins assembled in impossible configurations— legs sprouting where

arms should be—as well as nude females wrapped with string to create the effect of misassembled joints. One would move the

story to the present with one of Bellmer's aesthetic heirs—Cindy Sherman—whose deliberately nauseating photos of genital prostheses

in the 1993 Whitney Biennial were appropriately placed near an installation by another artist that featured a "puddle" of

rubber throw-up.

These are not, however, the doors that interest me. Unlike icons such as Elvis and Marilyn, Barbie is a corporate property.

And what distinguishes much of the best art using Barbie is that it has had to be produced almost surreptitiously. Mattel

wishes to impose its authorized vision on the public, but the public has other plans. Barbie colonized people's imaginations

in childhood, and they are impelled to bear witness. Some distort and pillory the doll; others place it on a pedestal. But

always, the unauthorized witness-bearers take a risk. The corporation cannot have any old Tom, Dick, or Jane promulgating

his or her personalization of a corporate-owned icon.

Such a personalization could "damage" the icon's image, or, worse, divert money away from the corporation. So the corporation

has three choices: It must co-opt the artist's work, as, in a sense, was done with the Warhol image; Mattel's permission—not

simply that of the Warhol estate—is required to reproduce it. It must commission art and impose "guidelines." Or it must do

its best to squash it.

What further complicates the relationship of Mattel to the contemporary art scene is that many of Mattel's early corporate

products (as well as the doll itself) are themselves works of art—exquisite miniatures that are, with aesthetic justification,

preserved by collectors. Then there's the fact that art these days involves borrowing images. From Barbara Kruger's political

collages to Richard Prince's manipulations of commercial photographs, "art" is about appropriation. Among its tenets, postmodernism

suggests that no work of art or text is anything other than a reassembly of citations; thus, if all art is citations, all

art is fair game to be cited.

What does it mean to cite Barbie? For baby boomers, Barbie has probably the same iconic resonance as certain female saints—though

not the same religious significance. But how different the art of the Renaissance would have been if the Roman Catholic Church

had required painters to place a trademark symbol on frescoes interpreting God and the saints. This is not, however, to imply

that the Church would have disapproved of such an arrangement.

"I don't think the College of Cardinals used terms like 'copyright' or 'registered trademark,' but let's face it, the scripture

was registered in essence and highly controlled by the Church," said Robert Sobieszek, curator of photography at the Los Angeles

County Museum of Art and author of

The

Art of Persuasion: A History of Advertising Photography.

"Somebody like Raphael was perhaps one of the greatest commercial artists who ever lived. He had a great client called the

Church; he had a great set of art directors called the College of Cardinals; and he had a great product—salvation. He was

doing commercial illustration to sell a philosophy—the history of Christianity or Catholicism. The fact that in the twentieth

century, we see genius in that, artistry in that, or invention in that is really beside the point."

Renaissance artists also had a strong inducement to stick close to scripture; those who deviated were dragged before the Inquisition.

Substitute law courts for Inquisition and you could be talking about today's corporate icons. Walt Disney's executors, for

instance, wouldn't permit his mice or ducks to be reproduced in

The Disney Version,

Richard Schickel's trenchant 1968 analysis of the aesthetic underpinnings of the "Magic Kingdom." The Disney organization

is notoriously vigilant about where and how its characters appear—appropriately, perhaps, licensing Mattel to produce doll

versions of figures from

Aladdin, Snow White,

and

Beauty and the Beast.

Yet certain emblems and symbols—Frigidaire, Xerox, Jell-0—crop up so often that it would be impossible for a corporation

to prosecute every unlicensed use.

What constitutes "fair use" for independent artists is now particularly relevant to Barbie, because Mattel has gone into the

Medici business—commissioning artists to use its icon in an authorized context: a picture book, the proceeds from which will

be given to an AIDS charity. The project resembles the advertising campaign for Absolut vodka, in which independent artists

were commissioned to cannibalize their styles in the service of a product. This is not to say that commercial art—work commissioned

for advertising or editorial use—cannot be "art"; photographers like Richard Avedon, Annie Leibovitz, and Sylvia Plachy, a

major contributor to this book, all work on commission. But, as was the case with the Renaissance painters and the College

of Cardinals, artists-for-hire frequently tailor their work to suit their clients.

Money also plays a part in "fair use." If an artist issues a series of images using a corporate icon exclusively to make a

buck, a corporation may have grounds for a case. But when an artist cites an icon in a one-of-a-kind work from which he or

she will realize scant profit, it may not be in the company's interest to take the artist to court. Copyright law, however,

encourages corporations to fire off cease-and-desist letters at the slightest provocation. "If a company doesn't go after

people that it feels are missing its icon, it's to the company's disadvantage," said Deirdre Evans-Prichard, curator of the

Language of Objects project at the Los Angeles Craft and Folk Art Museum, who has written on art and copyright issues. "In

a major court case, it would need to produce a file to show that it's been actively protecting its image."

No one could accuse Mattel of laxity in guarding its icons. Not wishing its trademarked dolls associated with

Superstar,

it joined A & M Records in sending threatening letters to Todd Haynes. More recently, it silenced Barbara Bell, an editor

of the New Age magazine

Common Ground,

who claimed to channel Barbie, "the polyethylene essence who is 700 million teaching entities." She now channels "a generic

eleven-and-a-half-inch plastic essence." Yet Mattel's behavior toward artists can also be baffling and unpredictable. It contributed

the dolls for David Mach's

Off the Beaten

Track,

a scorching piece that exposed it and its icons to ridicule.

Barbie has interested artists virtually since her inception. Second-generation abstract expressionist Grace Hartigan was perhaps

the first significant painter to incorporate Barbie imagery in her work. Her 1964 painting

Barbie

was inspired by a

Life

magazine article on the doll and its $136 wardrobe. "When I was a little girl, I had 'Patsy Ann,' a doll that was about my

age," Hartigan told me. "But here you had this doll with boobs and this castrated man and a wedding gown, and I just thought:

'That's our society.' I try to declaw the terribleness of popular culture and turn it into beauty or meaning. And I feel that

I have won—I've triumphed over it. It's witchcraft in a way. The triumph of this is that it's a terrific painting. I've used

the image, which I think is debasing to women, and I've turned it against itself and made it powerful."