Forever Barbie (30 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

With Hartigan's guidance—and the illustrated

Life

article in front of me— I managed to locate the representational elements in her painting: a pink face in the upper-right-hand

corner; a floor-length evening dress in the left foreground; a lone eye in the upper-left-hand corner; and in the center,

a single disembodied breast. "The final painting comes from the original imagery," she explained. "It's just highly abstracted."

Tomi Ungerer, who is perhaps best known for his whimsical children's book illustrations, also gravitated toward the doll in

the early sixties—not, however, producing objects for kids. Ungerer decapitated and dismembered the dolls, reassembling them—a

la Hans Bellmer—in constructions with sadomasochistic and coprophiliac themes. Perhaps inspired by Freud's Little Hans and

his investigations of doll "genitalia," one sculpture features a female torso hacked between its legs with a saw. Some constructions

consist only of the doll's legs in spike-heeled shoes; in others, tubes link the doll's genital orifices with its mouth. Ungerer's

"erotic doll sculptures" are now housed in the permanent collection of his work in the Musee de la Ville in Strasbourg, France.

By the late seventies and early eighties, when the first generation of Barbie owners had grown up, unauthorized Barbie art

began to proliferate. Independent artists have taken essentially two tacks when it comes to representing Barbie. There are

the reverential ones, who idealize the doll, and the angry ones, who use the doll for social commentary. Warhol was perhaps

the first of the reverentials—the sardonic self-censorers—who managed to convey even greater vapidity in his portrait than

exists in the doll's actual face. He was not happy with the image. "The portrait looks so bad, I don't like it," he recorded

in his diary on the day of its unveiling. "The Mattel president said he couldn't wait to see it and I just cringed." Once

an illustrator himself, Warhol and his scions are rooted in the tradition of commercial art; they include Mel Odom, whose

pastel renderings of Barbie are as sleek as the design of a corporate annual report. But to Odom, the seductive surface is

ironic. "I want to capture the soul of plastic," he told me.

Seattle photographer Barry Sturgill, whose work appears frequently in

Barbie Bazaar,

is also part of the reverential school. Widely regarded as the Irving Penn of Barbiedom, his photographs, characterized by

dramatic, high-fashion lighting, are about female glamour. He makes the doll look like a top model from the 1950s. "I like

the oldest face—the shelf-eyelash face," he explained. "She has a real 'don't mess with me, I'm Barbie' attitude. She was

supposed to be a teenager and she looks like she's thirty-five."

The angry artwork is usually not so polished; nor does it critique the same things. Some artists use Barbie to comment on

gender roles; some on colonialism and race; some on the consumer culture. Others, like Dean Brown and Charles Bell, use Barbie

to comment on art history.

Maggie Robbins, a 1984 graduate of Yale University, is one of the angry artists. By day, she answers the telephone and edits

copy at

McCalVs

magazine. By night, she hammers hundreds of nails into Barbie dolls. The effect of her hammering has been to transform the

dolls into unsettling pieces of sculpture. How the dolls are displayed dramatically affects how the viewer interprets them.

Mounted on a wall, they are images of female strength, curvaceous suns emitting potent metallic rays. On their backs, however,

they suggest other things: victimization, vulnerability, impalement by what Virginia Woolf termed "the arid scimitar of the

male."

It's hard not to view Robbins's work without asking: Is it art or therapy? But after seeing her

Rotating Barbie

in a group show at Richard Anderson, a SoHo gallery, in 1993, I had to vote for "art." The piece, which she made as a birthday

present for her ex-husband, is a kinetic sculpture involving reassembled Barbie parts; when activated, the figure lurches

about as if it had been battered and is trying to crawl from its assailant. I couldn't take my eyes off it; nor could anybody

else. People talked about it outside the gallery—sighing with relief because the artist was a woman. Had it been executed

by a man, it might have been read as an exhortation toward violence, instead of a critique. "It's about being angry about

everybody wanting to look like a Barbie," Robbins told me. "It's definitely much more anti-the-society-that-brought-you-Barbie

than it is antiwoman. Because Barbies aren't women."

Yet to observe Robbins's work is to be curious about the gender of the artist. Christopher Ashley, who directed Paul Rudnick's

Jeffrey

off Broadway, owns one of Robbins's

Barbie Fetish

series—the dolls impaled with hundreds of rusty nails. As Robbins tells it, his visitors become visibly less tense when they

learn it is the product of female hands. But even Robbins isn't entirely at ease with the ferocity in her work. "Putting the

nails into Barbie's face, into her eyes, was really, really hard to do," she said. "And the weird thing was: She didn't stop

smiling."

When I visited Robbins in her Brooklyn studio, I found some of her Barbie mutilations so brutal I could scarcely look at them.

In one, titled

Berlin Barbie,

Robbins has used carpet tacks to pin a blond doll to a pre-World War II German map. The glossy black tacks encrust the doll

like a fungus; they suggest the eruption of rot from within. Robbins began the piece in the summer of 1991, while she was

going through a divorce. She had spent time in Berlin with her husband in May and went back alone in August. She wanted the

piece to address not only her personal upheaval but also the doll's Teutonic roots. (Mattel will no doubt be pleased to learn

that Robbins has temporarily shelved her Barbies to work with another iconic female. She wrote the libretto for

Hearing Voices,

an opera about Joan of Arc, with music by composer Robert Maggio, which premiered at the University of West Chester in West

Chester, Pennsylvania, in December 1993.)

Robbins is one of a number of young female artists who use the doll to critique women's societal roles. Susan Evans Grove,

a photographer and a 1987 graduate of the New York School of Visual Arts, is another. In her Barbie work, shown at Manhattan's

Fourth Street Photo Gallery in 1992, Grove takes Barbie out of the sanitized "America" that Mattel invented. She succumbs

to the blights that afflict real women: homelessness, drug addiction, rape, domestic violence, sexual harassment, menstruation,

skin cancer— a glossary of female misfortunes. "It was definitely cathartic for me to make all these bad things happen to

her," Grove told me. "The one that got 'skin cancer' actually was

my

Malibu Barbie. She developed mold, poor thing." Grove's anger stemmed from the fact that she herself was dismissed as a Barbie.

"Because I was short and light and fair, people assumed I couldn't do anything," she said.

Julia Mandle, a performance artist and 1992 graduate of Williams College, understands Grove's irritation. Although she now

sports a Susan Powter haircut, she was once very Barbie-esque, which provoked incidents that caused her to revise her look.

The first occurred when she was a high-school senior visiting colleges and a male upperclassman helped her gain admission

to a campus pub. " 'Do you have any female friends who look like me so I can borrow their I.D.?'" she asked him. "And he said,

'Oh, there are probably a thousand girls here who look like you.' "

With her long blond hair and perfect figure—she had been bulimic since adolescence—Mandle admitted that there probably were.

But the remark "stuck with her," and contributed to her anger, which erupted in a 1992 performance piece called

Christmas Consumption.

Mandle, a Washington, D.C., resident, mounted the piece at the height of the December shopping season on a Georgetown sidewalk.

To set the stage, she filled a shopping cart with diet literature and encrusted it with Barbies and Barbie-like dolls. She

chalked eating-disorder statistics on the pavement. Then she transformed herself into a grotesque parody of Barbie— donned

a lime-green bikini, platinum wig, and flesh-tone body stocking— and performed calisthenics to "Go You Chicken Fat Go," an

exercise anthem. "The top kept slipping down," she recalled, "and guys would sort of come across and look, because from across

the street it looked like I was wearing nothing." Fox News filmed her and shoppers, seeing the wire cart and assuming she

was homeless, gave her money. "One reaction I had was a boyfriend pulling his girlfriend over and saying, Tm trying to get

her to exercise, too; what should I do?' He was completely oblivious," she said.

Over a decade earlier, SoHo-based photographer Ellen Brooks, who received her M.F.A. from UCLA in 1971, critiqued the glorification

of women's helpmeet status with fashion dolls. Three of her pieces—

Balancers,

Guarded Future,

and

Silk Hat

—appeared in the 1983 Whitney Biennial. "I wanted the doll to symbolize this kind of glamorous but secondary position," Brooks

told me. In

Guarded Future,

a sinister-looking magician and his female assistant hover over a malignant, spherical egg.

Revolvers,

which was not included in the Whitney show, explores a similar power relationship: a seated male orders his female assistants—

festooned with showgirl feathers— to balance, like seals, on spinning balls.

Brooks did not, in fact, work with Barbie, but with Kenner's Darci— applauded by doll expert A. Glenn Mandeville as "the outstanding

fashion doll of the late 1970s." As far as Brooks was concerned, however, a Darci was a Barbie was a problem, and she didn't

want her preschool daughter going near any of them. "But I couldn't very well say to her, you can't play with these," Brooks

recalled. "Because she's watching me play with them—creating these worlds." Brooks hasn't worked with dolls since 1984, but

she has had oblique contact with Barbie: Ken Handler's daughter frequently babysat for her.

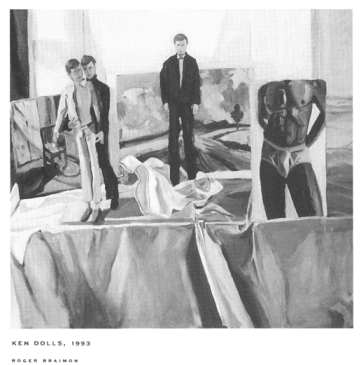

Gender is also a concern of Bolinas, California, photographer Ken Botto, whose photographs of toys were included in the 1992

"Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort" show at New York's Museum of Modern Art. But unlike Brooks and her aesthetic successors,

he doesn't see the early Barbies as constrained by their femininity. To him, they are powerful, dominatrix figures, sexually

linked to Nazis and robots, looming portentously over impotent Kens. "The early Barbie had an attitude on her face; it wasn't

blank," he told me. And his compositions, described by writer Alice Kahn as "Barbie Noir," were derived from the Helmut Newton

S&M aesthetic that cropped up in late-seventies fashion photography. His current work focuses on ancient matriarchal power.

Influenced by the writings of Camille Paglia, he has linked Neolithic goddess imagery to modern pornography to Barbie.

For Native American artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Hollywood's invented "America"—the "America" of cowboy heroes vanquishing

Indian villains—is a myth to be exploded and mocked. She does this in her 1991 piece,

Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed

by U.S. Government.

The work features "Barbie Plenty Horses" and "Ken Plenty Horses"—Mattel archetypes customized with names from the Flathead

tribe to which she belongs. The doll's outfits tell the story of what happened to her tribe over a century ago, when the U.S.

government forced it to move from its traditional home to a reservation several hundred miles away. Smith's humor is mordant:

her doll accessories include "small pox suits," a by-product of infected blankets issued by the government, and one of several

tribal headdresses "sold at Sotheby's today for thousands of dollars to white collectors seeking Romance in their lives."

Produced to coincide with the quincentennial of Columbus's arrival in America, or as Smith puts it, "five hundred years of

tourism in this country,"

Paper Dolls

sprang out of the "trickster" or "coyote" component in her personality. "I always think that you can get your message across

to people with humor better than you can in politicizing it in a dour sort of way," she told me. She also felt that "telling

a true story about the reality of my family" would be more affecting than compiling a "laundry list" of complaints.