Forever Barbie (26 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

"I don't buy any of the bad press that's attributed to the Barbie doll and her image," he concludes. "Jealous people always

make false accusations about things that they feel inferior to."

While I would not have expressed it in a sentence ending in a preposition, I can understand "Resident"'s indignation. It must

be burdensome, when you have an intense emotional relationship to a thing, to endure the callous, uncomprehending remarks

of people. Or to yearn, as Bly puts it, for a "Woman with the Golden Hair," and end up stuck with . . . a woman.

M

idway through my interview with Jan, a thirty-three-year-old business writer who lives in New York City, she asked me not

to use her real name. For her, to talk about Barbie was to talk about her mother. It was to recall her disquietude on the

eve of puberty. Jan had learned firsthand how a young woman's feelings about her changing body and awakening sexuality can

be poisoned by a parent. And she had learned this wordlessly—through a doll.

In

The Second Sex,

Simone de Beauvoir notes that in both French and English, a "doll" is a female adult, and "to doll up" means to don fussy,

feminine clothes. This, she feels, is more than a linguistic coincidence. Not only men but also women objectify women, and

they begin by objectifying themselves. A woman "is taught that to please she must try to please," Beauvoir writes. "She must

make herself object; she should therefore renounce her autonomy. She is treated like a live doll and refused liberty. Thus

a vicious circle is formed; for the less she exercises her freedom . . . the less she will dare to affirm herself as a subject."

Clearly, this objectification existed long before Barbie, but it may have fresh meaning in the post-Barbie world.

It certainly does for Jan, an Asian American who was born in South Korea and adopted by a German-American mother and an Italian-American

father. Jan spent her childhood in Orange County, California, and graduated from high school and college in Indiana, where

she managed to be both "popular" and smart—a pom-pom girl who was an honor student and the editor of the school newspaper.

Jan's first encounter with "the whole Barbie phenomenon" took place in California in 1965. "I must have been five or six,"

she told me. "That year, for Christmas, I got a Skipper doll and a little forty-five of Gary Lewis and the Playboys' 'She's

My Girl,' and all day I had Skipper bouncing around to this song. She was a dark-haired Skipper, and she very much had that

sixties look—eyeliner and little bangs and long hair. I thought Skipper was the end-all and be-all of the earth, until I phoned

one of my friends to compare gifts. She started talking about how she had gotten this Barbie, which was a much different kind

of doll. And I immediately felt rooked—why had I gotten the little sister? Why hadn't I gotten the star of the show?"

Jan's adoptive mother argued that the younger doll was closer in age to Jan. But, Jan recalled, "It made me feel in playing

with other girls that I didn't have what it took. Because all I had was a Skipper, I could never really get into the whole

dating thing. I could never have this rich fantasy life—meet a man, have romantic love. I was always relegated to being the

little sister."

Nor did Jan's identification with Skipper end when she outgrew dolls. "I have never felt particularly pretty or attractive

or sexually interesting. I have always thought that I was more like, not a little sister, but an androgynous person."

This was not the revelation I had expected from Jan—chic, downtown Jan in her stylish black suits and crimson lipstick—who

had competed in beauty contests as a teenager. I had expected her to talk about racial identification: how it felt for an

Asian American to play with a doll that coded Caucasian standards of beauty. But all Jan wanted to discuss was Barbie's voluptuousness.

"Barbie always looms," Jan said. "That sort of ideal looms—and other women have it. Other women possessed these dolls; other

women learned the secret. Maybe this is taking this Barbie thing too far, but I feel like other women had a certain kind of

girl experience that I didn't—that they understood something about being sort of seductive and perky that I didn't get. I

was always kind of a gal-along-for-the-ride, never feeling I could identify with the Marilyn-Jayne Mansfield-Barbie character."

By withholding Barbie, Jan believes, her mother deliberately tried to stunt her sexual development. And it nearly worked:

Despite her cheerleader looks, she projected so much standoffishness that she scared boys away. It wasn't until she was eighteen

that she had her first date. Fortunately, her father, an engineer who wore Vargas Girl cuff links and joked about "va-va-va-voom

actresses," projected a different message. "My mother was a very threatened person," Jan said. "Because she was very unattractive.

And my father was quite handsome. I think she felt threatened by me sexually—by any woman who was attractive.

"You know what dolls my mother did give me?" Jan suddenly blurted. "Trolls! I never had a Barbie house but I had a troll house.

I was thinking: Is this what she wants me to identify with—these horrible things with purple hair?"

Today, no one observing Jan and her handsome husband—"a cross between Jeff Bridges and Jeff Daniels," she says—would suspect

that she had a Skipper Complex. Yet just as I will never quite shake the legacy of Midge, Jan has been forever burdened with

Skipper. Jan, however, doesn't scapegoat the doll; in therapy, she learned to distinguish between the message and its messenger.

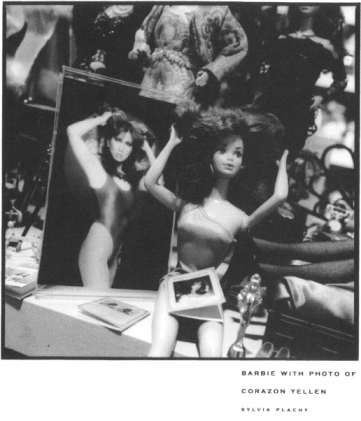

That distinction, however, has increasingly begun to blur. The Barbie doll has become so synonymous with female sexuality

that at Sierra Tucson, a trendy Arizona substance abuse clinic, women in treatment for "sex addiction" are required to carry

one with them at all times. Lugging around Barbie, Alethea Savile explained in London's

Daily Mail,

forces them to reflect constantly on their objectified sexual selves.

Nor is it news that people connect Barbie's oddly proportioned body to adolescent eating disorders. According to a group of

researchers at University Central Hospital in Helsinki, Finland, if Barbie were a real woman she'd be so lean she wouldn't

be able to menstruate. Her narrow hips and concave stomach would lack the 17 to 22 percent body fat required for a woman to

have regular periods—and a failure to menstruate is one of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa, a condition of self-starvation

that principally afflicts young women. Significantly, though, Barbie isn't alone in her emaciation. The same researchers found

that beginning in the fifties, when Barbie was introduced, life-size department-store clothes mannequins began to be made

with the appearance of 10 percent body fat. Mannequins from the 1920s, by contrast, were stouter: Were they suddenly made

flesh, they would have no trouble getting their periods.

This thinning down might be of greater alarm if it were without precedent, which it isn't. In the history of art, representations

of the figure have often been distorted so that their drapery would fall in a pleasing fashion—and Barbie, like a clothing-store

dummy, is a sculpture that exists to display garments. "The body of the

Ceres

in the Vatican Sala Rotunda is visibly distorted in some dimensions for the sake of displaying the clothes to advantage, rather

than the other way around," Anne Hollander notes in

Seeing Through Clothes,

and she doesn't exaggerate. The statue's giant breasts seem to sprout from its shoulders, and there is room for a breast and

a half between them. Nor was such distortion unusual in classical sculpture. "The identical body without the dress would look

somewhat awkward, whereas a perfectly proportioned body could not wear such a fully draped costume without looking swamped

and bunchy," Hollander says of the

Ceres.

The same could be said of Barbie.

The controversy over Barbie's thinness heated up in 1991, when High Self Esteem Toys of Woodbury, Minnesota, introduced "Happy

To Be Me," a doll whose measurements were alleged to be more "realistic" than you-know-who's. Abetted by a tenacious PR firm,

Cathy Meredig, Happy's developer, took her crusade to the press. Two percent of girls in the United States become anorexic

at some point in their lives, she explained to

The New York

Times,

15 percent become bulimic, and 70 percent view themselves as fat. "I honestly believe if we have enough children playing with

a responsibly proportioned doll that we can raise a generation of girls that feels comfortable with the way they look," she

told

The Washington Post.

And the press embraced her. From

Allure

to

People,

pro-Happy pieces sprang up like dandelions in a summer lawn. The vice president of the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa

and Associated Disorders in Highland Park, Illinois, called Happy "a much-needed development." Yet by 1994, Happy was virtually

history. Mothers may have told reporters, "Wow! A doll with hips and a waist," but they bought Barbie.

Meredig blames Happy's poor showing on Mattel's "stranglehold on distribution channels," which, given the way it snuffed out

competitors like Hasbro's Jem, may have some truth. But it strikes me that Meredig is fighting something far larger than a

toy company—even one big enough to be listed among the

Fortune

500. One of the clippings in Meredig's own press kit confirms that Barbie doesn't instigate but merely reflects society's

notions of beauty. Photocopied alongside a Minneapolis-St. Paul

Star

Tribune

article on Happy is the giant ad printed next to it—for "Southlake Hypnosis," a weight-loss clinic in Edina, Minnesota. "I

just lost 30 pounds and I feel terrific," the ad says in type larger than Happy's headline. "Now I can wear a two-piece swimsuit!"

Meredig claims to have based Happy on the Venus de Milo, but her classical allusion masks an ignorance of the historical relationship

between the sculpted figure and its drapery. The Venus, as Hollander points out, may have ended up armless by chance, but

she was "legless by design"—and without the heavy folds obscuring her stumpy legs, even her contemporaries would have thought

her dowdy. By contrast, Charlotte Johnson, Barbie's first dress designer, understood the historical interdependence between

the figure and its drapery. She also understood scale: When you put human-scale fabric on an object that is one-sixth human

size, a multilayered cloth waistband is going to protrude like a truck tire around a human tummy. The effect would be the

same as draping a human model in fabric made of threads that were the thickness of the model's fingers.

Because fabric of a proportionally diminished gauge could not be woven on existing looms, something else had to be pared down—and

that something was Barbie's figure. One wonders how Meredig could have failed to notice the glaring incongruity between the

scale of human-sized cloth and that of its miniature wearer. Or did Meredig so obsess on the naked doll that she forgot that

girls were supposed to dress it?

Even in the raw, however, Happy leaves much to be desired. She is so cheaply manufactured that she makes Barbie look like

an heirloom. When I handled an actual Happy doll, the first thing I noticed were not its measurements ("36-27-38" to a fashion

doll's "36-18-33," Meredig's press materials said), but its receding hairline. Its hair sprang out of its head in widely scattered

clumps, as if its balding pate, like that of a desperate middle-aged man, had been reforested with plugs. Then there was the

hair's creepy texture. Whatever else one may say about Barbie, her hair feels like hair. It is made out of Kanekalon, a fiber

used for human wigs, which Mattel designer Joe Cannizzaro arranged to have extruded in lengths long enough to meet the requirements

of the sewing machines used on doll heads.

In appealing to educated, aesthetically minded parents concerned about body image, Meredig seemingly forgot how snobbish such

parents can be about cheesy toys. Even Roland Barthes, who rhapsodized about plastic's versatility, turned up his nose at

plastic playthings. Such toys, he said, lack "the pleasure, the sweetness, the humanity of touch" that their wooden counterparts

possess—fancy words to express a plain old "prejudice" against them, suggests psychologist and

Toys as Culture

author Brian Sutton-Smith.

Nor is it as if Happy had no impact on Barbie. Ever watchful of its competitors, Mattel has included some very Happy-esque

modifications on the dolls in its 1994 line. These include Gymnast Barbie, a doll with flat feet (like Happy's) that can stand

without support, and Bedtime Barbie, a stuffed doll with a plastic head that I predict will be a favorite with mothers. Far

from being a sexpot with a wardrobe from Victoria's Secret, Bedtime Barbie wears a frowzy flannel housecoat and fuzzy slippers.

She is Slattern Barbie, Cellulite Barbie—a doll with thick ankles, sagging breasts, and squishy thighs—as unthreatening to

Mom as Roseanne Arnold before her surgery.

But even if Meredig had produced an aesthetically pleasing doll—one that didn't wear chalk-colored, Dusty Springfield lipstick

or require Rogaine—she still probably wouldn't have dethroned Barbie. For a kid, being stuck by Mom with a Happy is a lot

like being stuck with a Skipper— or perhaps worse, since while Skipper may not be sexually mature, she at least conforms to

societal norms of attractiveness. And those norms are, of course, at the center of this fuss: In a world where women's bodies

are objectified and commodified, is it better for a girl to aspire to an arbitrary standard of "perfection" or to avoid disappointment

by keeping her standards low?