Forever Barbie (23 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

The hodgepodge of styles in Barbie's house might be interpreted as a reflection of her class anxiety. "Having a period room

or a correctly designed room at a certain point becomes very risky socially," Betsky explained. "Because it means that you're

sort of snooty." To attract the maximum range of buyers, her furniture could convey neither hoity-toity nor hoi polloi. "If

your room is eclectic, it means you've inherited things," he said. "It means that you have a family history and you're not

just right off the boat. So it becomes very acceptable to have pieces that show that if you didn't inherit them from your

grandmother who lived in West Essex, then at least you had enough money to go on a trip to West Essex and pick up a few pieces,

even if they don't quite go with what you got downtown at Macy's."

Barbie also came on the scene at a time when labor-saving devices were liberating middle-class wives from the drudgery of

household chores. As affordable mechanical servants replaced the costly human variety, class distinctions blurred. In 1963,

New Jersey's Deluxe Reading Corporation issued a "Dream Kitchen" for Barbie-sized dolls that was a monument to the democratizing

effects of technology. What its young owner got was no less than the control center of a suburban spaceship—with a deluxe

maize-colored range, a chrome-plated turquoise refrigerator, a sand-colored dishwasher, and a magical garbage disposal tucked

away in a salmon-colored sink.

One of Barbie's odder flirtations with archaism came on her 1971 Country Camper—a democratizing vehicle that made pastoral

retreats, once restricted to country-house owners, available to anyone who could afford a car. In order to invest the camper

with luxury, its plastic kitchen cabinets have ovoid Baroque moldings—the sort of thing one would see in their original incarnation

at Versailles.

Not surprisingly, when Barbie achieved superstar status, her houses became more ostentatious. Yet even Barbie's three-story

town house, with its Tara-like pillars and ersatz wrought-iron birdcage elevator, is an outsider's interpretation of upper-class

life. Authentic valuables are to Barbie's possessions what a pungent slab of gorgonzola is to "cheese food"; her furniture

and artwork would not look out of place in a Ramada Inn. For all her implicit disposable income, her tastes remain doggedly

middle- to lower-middle-class. As pictured in the catalogue, the town house also reflects

Dynasty

thinking. Both Ken and Barbie are absurdly overdressed—he in a parodic "tuxedo," she in a flouncy confection that barely fits

into the elevator.

If Barbie was supposed to be putting on airs, she was doing it ineptly. She bought a lot of things, but they were things whose

selection required no connoisseurship. Barbie is a consumer, not a climber. Except for her body, which is slimmer than the

average woman's, Barbie is the great American common denominator. She is rich, but not top-out-of-sight; smart but not cultivated;

pretty but not beautiful. Far from embodying an impossible standard, she represents one that is wholly achievable. Even the

destitute and bottom-out-of-sight can use her as a template for their daydreams.

OF COURSE WHEN I SAY BARBIE'S STATUS IS WITHIN THE grasp of most Americans, I mean North Americans. In Latin America, where

blond Barbie outsells all other dolls, Barbie leads a life that few of her young owners will ever replicate. Like Mickey Mouse

and Ronald McDonald, Barbie is a pop cultural colonist, a "global power brand," as Mattel vice president Astrid Autolitano

puts it.

Because of import restrictions, Mattel has had only two affiliates in Latin America—Mexico and Chile—but the North American

Free Trade Agreement will probably change that. Other countries—Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Venezuela, and Colombia—have been

served by local licensees. Rather than hindering Barbie's market penetration, however, this simply led to a new dimension

in her class mutability. In markets with limited buying power, Mattel or its licensees introduced dolls at lower prices. "Those

lower-price dolls basically offer us an opportunity to reach the lower classes, which we call in our jargon, 'Class D'—so

as not to say 'lower classes,' " Autolitano told me. On the positive side, this makes Barbie a less-exclusionary product;

girls of negligible means can dip their toe in the chlorinated swimming pool of North American consumption. On the negative

side . . . well, Ken Handler—after whom the male doll was named—has a few thoughts.

Now entering his sixth decade, Ken Handler is no stranger to South America. He spends half the year there, slogging through

swamps, consulting with shamans, stalking indigenous herbs. While on the board of directors of Bronx AIDS services several

years ago, he became interested in antioxidant drugs, which many believe can inhibit the cell mutagenesis that causes cancer.

The strongest antioxidants, he says, are harvested near the Equator, where they have been toughened by exposure to intense

ultraviolet light. When I spoke with him in the winter of 1993, he was raising $7 million to build a laboratory in Ecuador

to refine these drugs, and working with a team of physicians to get FDA approval for them.

Handler does not look like his plastic namesake. He is soft-spoken and erudite, with a high forehead, shoulder-length gray

hair, and a shaggy gray beard, resembling a mature self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci. Perhaps as a reaction against his parents,

he has embraced archaism with a vengeance. He restores eighteenth- and nineteenth-century town houses in Greenwich Village,

and lives in one of them. He plays the harpsichord, specializing in music from the seventeenth century. He spent years on

the board of New York's Metropolitan Opera. He admires his parents—"They provided a home with a lot of love," he insists—but

he cannot bear the dolls they invented.

To his parents' bewilderment, Ken, as a child, had no interest in toys. He spent his free time reading, playing the piano,

or listening to jazz or classical music, which led to his majoring in music at the University of California at Los Angeles.

He remembers his youth as a long struggle with his sister, Barbara, who did not go to college. Even something as innocuous

as a family drive frequently exploded into a battle for control of the car radio. Ken wanted to listen to opera; his sister

Barbara demanded rock 'n' roll. "Every time I got my choice, which wasn't very often, she would have a fit," he said. "God,

she knew how to pull the strings on Mom and Dad.

"My sister was a conform freak," he told me. "She loved Barbie. If you'd seen her at age sixteen to seventeen, she

was

Barbie. She went to the beach with her friends; they had the van; they did that life."

Barbara, a comely redhead now well into her fifties, has a policy of not giving interviews. The numerous snapshots of her

in Ruth Handler's family album, however, suggest that she is less allergic to being photographed. "It's a shame she won't

talk because she owes a lot to that little doll," Ken said. "She used to sell towels," he continued, referring to a bath shop

she once ran in Beverly Hills. "And then she decided she wasn't going to sell them anymore. I think she likes to play golf.

She used to like to play tennis, then she hurt her leg or something . . . she's had kind of an easy life."

Talking with Ken was a little like playing

Jeopardy!

His conversation leapt from virology to Verdi, from the frontiers of medicine to Met musical director James Levine. I found

myself thinking of Nick in

35-Up

—the professor who claims to have close ties to his family, yet who, because of his education, is effectively living on another

planet.

"I don't think we've ever had a Barbie in the house," Ken said with amusement. "Philosophically, I didn't want my children

to play with it. My oldest [daughter] is so uniquely talented that I've always felt that any gesture toward looking a certain

way or being a certain way was not a positive thing. If she had said, 'Dad, get me a Barbie,' I would have gotten it for her.

But she knew about it; she'd seen it; she never asked—so I never got it." Samantha, his oldest, currently makes her living

as a psychic; but his second daughter, Stacy, an art student, also expressed no interest in the doll. Nor did his son, Jeff,

a high-school senior.

"I felt a lot of indignation about the effect the dolls had on impressionable children who are either overweight or couldn't

make themselves into that image and felt inferior as a result," he told me. "This bimba—and I say 'bimba' because it's feminine—never

has a serious thought. And she has a figure no young lady could ever achieve without a severe anorexic leaning or surgery."

When I suggested that these days Barbie has a fairly impressive resume, he cut me off. "They're not really careers—they're

putting on a costume and pretending. . . . It's no different than some sort of drag show."

Ken's parents don't understand his irritation. "They've never meant for this doll to have—they never see the negative side

of it. They don't understand it; it's beyond their ken, to make a pun . . . to them it's just good play. And yet they're very

vain people, my parents. They care if you're a little overweight. They care if—I had lost a few pounds because I got these

little critters that I always pick up when I go to South America. And my parents said, 'Gee, you look terrific—you lost five,

ten pounds or something.' "

Critters or no, Handler is rhapsodic about South America. The curative values of the virgin rain forest are not merely those

of the plants he gathers; they are metaphorical. They have to do with the purity of the air, of a life unstriated by social

class and uncluttered with material possessions. Never a beachgoer when he lived in Los Angeles, he loves the South American

shore. "I like walking down the beach and watching the fisher-men fish and the pigs run wild. It's nice going to the beach

with a bunch of pigs.

"I'll tell you what I would like to do with Barbie and Ken if they were to suddenly come to life," he said, "provided they

could learn enough Spanish because nobody speaks English down where I go—most of them speak Indian languages. I would like

to take Barbie and Ken and train them as ethnobotanists, so that they

J

would take the skills they learned at the university at Pepperdme or Malibu or wherever they go to school, and work with the

indigenous people. Teach them how to tell time with a wristwatch. Motivate them in learning the skills of their antecedents,

through the shamans, who are still alive."

He grew more animated. "I'd like Barbie and Ken to take their blond selves—

rubino

or

rubina

means blond down there—and tan themselves in the sweat of the equatorial jungle sun and give themselves to people that desperately

need to learn from them. If Barbie and Ken would come down there with me, I would make sure they have enough work for the

summer. But they couldn't drive their van down there, unless it was a four-by-four. And the banditos—if they saw that van,

they might want it. So Barbie and Ken might end up having to thumb their way through Guatemala or someplace." He chuckled.

I didn't have the heart to remind him that Barbie and Ken were already there. With their van. And that they probably had taught

something to the indigenous people. Just not ethnobotany.

I

f people subscribe to the theories of men's movement mythologizer Robert Bly—and the sales of his book

Iron John

would suggest that they do—gentlemen have preferred blondes since the dawn of history. A "Woman with the Golden Hair" dances

through the male unconscious, not a "flesh and blood woman," but a "luminous eternal figure," Bly says. From her face emanates

a whisper: "All those who love the Woman with the Golden Hair come to me." Men search for the perfect embodiment of this being,

projecting their hunger onto models, centerfolds, flight attendants, and aerobics instructors. But such desire is not exactly

sanguine for its objects: "Millions of American men gave their longing for the Golden-Haired Woman to Marilyn Monroe," Bly

writes. "She offered to take it and she died from it."

Scion of a sex toy, Barbie, far more than any human, is equipped to withstand such toxic projections. Age cannot wither her

nor custom stale her infinite plasticity. "I think if you look at the silhouette of the

Playboy

Bunny, it looks like a Barbie doll," retired Mattel designer Joe Cannizzaro told me. "So do men want to date a Barbie doll?

Probably. But do men notice it? Only if shown. They wouldn't go looking for it."

Well, not at Toys "R" Us, anyway. But according to Dian Hanson, editor of

Juggs, Leg Show,

and

Bust Out!,

Barbie's body, even without detailed genitalia, is proportioned to inflame all the common permutations of heterosexual male

desire.

Hanson, born in 1951, is one of America's preeminent female pornographers. Unlike that of Susie Bright, editor of

On Our Backs,

a magazine "for the Adventurous Lesbian," Hanson's audience is primarily straight men. She credits her success to market research:

she asks her readers what they want and they tell her. Readers of

Leg Show,

her magazine for foot fetishists, "tend to be white-collar, educated people with computers," she told me. "They write me a

lot. The letters pour in every day. I've asked them to explain: Do you know where your fetish came from? What are your earliest

memories? And I've learned a great deal. A lot of what I know, I know from these guys directly."

Hanson does not have the tough look that one might expect from a sultana of smut. Lean, fit, and proportioned like a fashion

doll, she wears little makeup and has long, healthy blond hair. Her features are as even as a cover girl's, and her smile

is so wholesome she could sell toothpaste. Slightly tan, she radiates a sort of patrician outdoorsiness; one could imagine

her teaching sailing or skiing at a tony resort. When I met with her at her SoHo office on a bone-chilling winter day, she

was wearing blue jeans and L.L. Bean duck shoes—not what I'd anticipated. Her office, however, did not disappoint: nearly

every flat surface was covered with brightly colored genital prostheses or stiletto-heeled pumps—marabou-trimmed mules, rhinestone-studded

slippers—many of which, because of Hanson's large feet, were bought in transvestite boutiques.

"One of the reasons my magazines are very successful is because I realize you can't separate sex from love," she explained.

"When a man has a breast obsession, he's looking for security and love and blissful, mindless protection." This led her to

create

Bust Out!,

which features narrow-hipped professional sex stars with huge silicone breasts that, she says, appeal to men who grew up with

Barbie. "When the mother holds the baby up where the breast is, it's just huge—as big as his head if not bigger—and it's filling

his vision, filling his nose, filling his ears. Everything is blocked out by the breast, and the breast is comfort and safety.

The desire to have a breast as big as your head is really taking yourself back to that infantile period and being able to

lose yourself.

"I learned this really from doing

Leg Show,"

she continued. "The breast thing was so common I didn't think about it. But I had to figure out why men were obsessed with

feet and legs and groveling before them. I learned that men get security from legs, because when a little child is scared,

he grips his mother's legs. They're always trying to get up under the skirt, holding on to the legs—and the legs represent

safety. A loving mother may pick up the child and hold him, but a less loving, harsher mother may just leave the child down

there, so the legs are all he gets. When a boy with a stern, withholding mother grows up, he often fastens on a harsher, more

demanding woman as his love object."

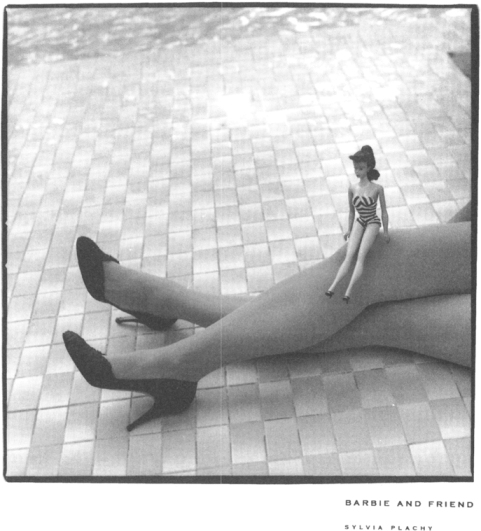

Such men also fasten on Barbie's fetishistic shoes, which "raise the foot, contort it, and display it as if it's on a pedestal—which

is precisely what most foot fetishists want. Foot fetishists think of the foot like the breast; and a man who likes the breast

wants to see it lifted up and displayed. He wants a big push-up bra. Men who are into breasts don't want to see the breast

just lying there. They really love those low-cut fifties dresses where they see cleavage really

displayed.

A shoe like Barbie wears does the same thing: It draws attention to the foot, much more than, say, a bare foot walking down

the street. You're taking the foot and you're elevating it. You're serving it on a platter."

But far from being symbols of female passivity—or devices that impede movement—spike heels can be interpreted as symbols of

strength. They make the wearer taller, so that she or he (the shoes are

de rigueur

with drag queens) towers over the nonwearer the way that Mom towered over her little boy. Nor do they mimic feminine curves;

they are sharp, pointy, masculine.

"Submissive men" who buy

Leg Show

are into "the highest, most dangerous, most hobbling heels because they see them as a symbol of feminine power," Hanson explained.

"Because they could be hurt by those shoes. They could be pierced. And they like being walked on with them."

You don't have to be a psychoanalyst to see how childhood experiences shaped Hanson's readers. She can even pinpoint the decade

a man grew up in by the type of hosiery that excites him. Men who were toddlers in the seventies (when their mothers wore

pantyhose) are turned on by pantyhose; older men prefer garter belts.

Nor are boys alone influenced by the earliest bonds with Mom. Children of both sexes are originally matrisexual, Nancy Chodorow

writes in

The

Reproduction of Mothering,

and remain so for most of their preoedipal period, or until they are about four or five. Freud, in fact, found that a girl's

infantile attachment to her mother has a major impact on both her succeeding oedipal attachment to Dad and her eventual connection

to men in general.

Hanson doesn't just grill her readers about the origins of their sexual desires; she has also probed her own. Brought up in

Seattle by parents who were part of a secret fundamentalist religion, she remembers Barbie as her beacon. Just as aspiring

doctors send their Barbies to medical school or aspiring models pose her on runways, aspiring pornographers—well, the doll,

Hanson says, made Hanson what she is today.

Hanson was nine when Barbie first appeared, and her parents, members of the Constitution party, a right-wing group similar

to the John Birch Society, refused to let her have one. They considered the doll—along with rock 'n' roll and

Mad

magazine—to be part of a conspiracy to sexualize "American youth and thereby weaken it, by making it promiscuous," she recalled.

"With my parents, it was always hard to tell whether it was the 'Communist Conspiracy' or the 'Jewish Conspiracy'—they sort

of melded together in my mind." But its pomps, her parents felt, would "enflame our sexual organs and ruin our white morality,

which was of course the basis of everything that made America great.

"My father said, 'The purpose of dolls in the life of girls is to train them to be good wives and mothers,'" she continued.

"And girls should play only with baby dolls so they can learn to care for real-life families. He felt—and his religion feels—that

women have no creative abilities, women have no place in the world except to support their husbands and raise their children.

I think Barbie probably turned my dad on. My dad is a very sexual person . . . and he saw Barbie's sexuality. But once Barbie

was proclaimed to be this sexual conspiracy object, she became much more provocative to me."

At first, Hanson would sneak off to friends' houses to play with their Barbies. But after about a year or so, when owning

the dolls didn't appear to have any ill effects on her cousins, her mother caved in and gave her one.

"When I got Barbie, it was like my parents had given me heroin," Hanson said. 'The first thing I did was strip all her clothes

off and marvel at her breasts and feel her breasts and look at her body and those tiny arched feet and the whorishly arched

eyebrows and the solid thick eyelashes and the earrings that stuck straight into her head." She paused. "They were pins. It

was very exciting to me to pull the earrings in and out. I did it to the point that they just fell out after a while."

Hanson usually played with Barbie in the company of her younger brother, who became a cross-dresser and committed suicide

in his twenties. "I was supposed to play with my sister but we didn't get along. My brother was more appreciative of Barbie's

sexuality . . . I had Barbie and Midge, and we used to parade them around naked in their high heels. We painted nipples on

them one day to make them more realistic. And we were mortified that we couldn't get the paint off. So my parents were going

to know that we had sexualized the dolls."

Nevertheless, because of the rituals of their religion, her parents' idea of "sexual repression" was not what everyone would

consider repressive. Her father, a chiropractor and "naturopath," practiced nudism, and her mother gave birth to the children

at home. "It was a sexually charged household," Hanson said.

"I lived out my own emerging sexual fantasies with Barbie," she continued. "I only wanted the sexy clothes, and my mother

wouldn't give them to me. She bought me childish clothes—a blue corduroy jumper. We'd put Barbie in it without the blouse

and the breasts would show. The two outfits that I coveted—and saved up money for, and had to fight with my mother over—were

both strapless: the pink satin evening gown that fit real tight. It could barely go over her legs it was so tight. And you

could pull her top down. The other one was the gold lame strapless sheath dress with a zipper up the back.

"I didn't like Midge because she didn't have a sexy face," Hanson said. "The old Barbie looked dominant: sharp nose, sharp

eyelashes—she was a dangerous-looking woman. And of course she had those symbols of power on her feet. . . . I don't consider

Barbie sexual anymore. I looked at new Barbies a year or so ago, and their faces were infantile—more rounded and childlike."

Hanson used Barbie to imagine her idealized future self, which in her case meant an object of male desire. "Barbie was an

adult woman whom I could examine," she said. "And I wanted very much to be Barbie." Nor was Hanson the only budding sex maven

to fixate on the dolls. "I definitely lived out my fantasies with them," Madonna told an interviewer. "I rubbed her and Ken

together a lot. And man, Barbie was

mean."

Likewise, Sharon Stone's thoughts in

Vanity Fair

suggested an autobiographical episode: "If you look at any little girl's Barbie, she's taken a ballpoint pen and she's drawn

pubic hair on it."

Hanson left home at seventeen and became a respiratory therapist. After a bad first marriage, she found herself divorced in

Allentown, Pennsylvania, where she met a man who was starting a sex magazine called

Puritan.

"I started working on that magazine and it was like a dream come true, to get to be a pornographer," she effused. "I wanted

to be appreciated in that way. I used to be a provocative dresser. I was very promiscuous. I'd wear hot pants and see-through

blouses and things like that. But as I've gotten older and more successful in my career, looking a certain way doesn't worry

me anymore. And I'm grateful—because there's nothing worse than being forty-one years old and still needing that kind of attention."