Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (47 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

“I was marched over to the nearest tree and put up against it. Two of the enemy were detailed as a firing party and were just taking aim when a senior officer came rushing up to them. He ordered the party not to fire and I was led away for interrogation.”

Seymour’s interrogator spoke good English with a faint American accent. This was Wilhelm Schneider of the Gestapo, a senior figure in the German intelligence hierarchy in Alsace-Lorraine. Seymour was left in no doubt about his options. “If I did not tell the truth it would be the worse for me.” He gave his name, rank, and serial number, but nothing more; when pressed, he admitted that he was part of a “recce party,” but refused to give any details of the mission. When Schneider pressed him to reveal the parachute drop zone, Seymour said he “gave convincing answers, but not true.” Taken to the nearby prison camp at Natzweiler-Struthof (the only concentration camp on what is now French soil), Seymour was given black coffee and a lump of stale bread, and then subjected to further questioning. At one point, Schneider produced a captured British wireless set, along with a onetime pad (the key to the British system of cryptography) and codes written on a strip of silk. “I replied I knew nothing about wireless.”

Over the next six months, Seymour was shipped from one German prison camp to another, and repeatedly interrogated. Often held in solitary confinement, he was forced to sleep on the floor with only a blanket for cover. His skin erupted with raging scabies and impetigo. After the first month in captivity, Seymour and a group of a dozen captured American airmen were loaded onto a cattle wagon and told they were being taken to Frankfurt for further questioning. The train was pulling into Karlsruhe when the city came under Allied air attack. The prisoners were swiftly offloaded and bundled into an underground shelter. An hour later, they emerged to find Karlsruhe “practically flattened and in flames,” and a very angry local population, intent on extracting summary vengeance.

“They were ready to lynch us if they got hold of us,” Seymour recalled. “Women were in hysterics. They had got the idea that we were part of the crews that had been shot down during the raid…They threw stones at us and anything they could lay their hands on. I was hit on the head by a brick. Persons passing us on bicycles struck us, men on the pavement made rushes at us between the guards, one in particular putting his arm around an airman’s neck and hammering his face with his fists. Had it not been for the action of the military personnel I am sure we would not have reached the station alive.”

A further succession of camps followed, each more brutal than the last. In mid-February 1945, Seymour was incarcerated in Stalag Luft III, near Żagan´ in western Poland, the camp made famous by the film

The Great Escape

. One morning, at five o’clock, he and the other prisoners were rousted from their beds and told to prepare to ship out. The Russian guns could be heard in the distance. According to Seymour’s account, the forced march to Stalag IX-B at Bad Orb, north of Frankfurt, would last forty-two days. He was now able to wear both boots, but still limping. The rations varied from appalling to nonexistent. For the first week, the prisoners “slept out in the snow with no blankets.” Many died from cold and starvation. Finally, they reached the camp. “By this time every man was weak and suffering from malnutrition, the majority were also suffering from dysentery of which I was one, many also suffered from frost bite.”

A fortnight later, a rumor swept the camp that the Americans were approaching, and two days after that the German commandant surrendered control to the senior British officer. “The German guards marched out, leaving the camp in our hands,” Seymour wrote. Stalag IX-B was liberated on April 2, 1945. Seymour was flown back to Britain and was treated at a military hospital until he was well enough to return to Sutton, where he immediately became engaged to his long-term sweetheart, Pamela Vaughan.

Seymour’s story was one of intense suffering, heroically borne. It was uplifting, even inspiring.

But it may have been quite untrue.

Seymour’s claim to have fought a single-handed action against dozens of Germans in the Vosges Mountains is distinctly dubious. According to one account, his leg was so badly injured he was being carried on a stretcher by two maquisards when the troop encountered the German patrol. Since Seymour was certain to be captured, he would hardly have been left behind with a valuable Bren gun.

Seymour’s commanding officer Henry Druce was emphatic: “He never fired a shot.”

At his war crimes trial after the war, Gestapo officer Wilhelm Schneider testified that, far from refusing to talk, Seymour had been most cooperative, since he had not only divulged details of the operation but had also “shown how to work the wireless set and cipher.” Another German officer, Julius Gehrum, confirmed that account: “The prisoner with the injured foot answered Schneider’s questions, and Schneider said to me afterwards ‘with this man we can begin something.’ ”

Schneider was cross-examined by Major Hunt, the chief prosecutor for the 21st Army Group.

“You interrogated Seymour, did you not?”

“Yes.”

“And you thought you could get something out of Seymour, did you not?”

“Yes.”

“And you have said that you did get something out of Seymour, have you not?”

“Yes.”

“And unless you are lying, you got some very important information out of Seymour, did you not?”

“It was very important at the time.”

“And it was military information, was it not?”

“Yes.”

Schneider implied that far from being coerced and threatened, Seymour had been willing to talk from the moment of his capture. “He was very annoyed that they had left…they just left him lying there in his helpless state.”

Hunt then cross-examined Seymour, pointing out repeatedly that while other captured members of the SAS party had been executed within hours, his life had been spared. At times, it seemed as if Seymour, and not Schneider, was in the dock.

“You cannot give me any reason why you were not shot, can you?”

“None at all. My only thought about it is that I was the first to be captured.”

“I am a little puzzled. You gave false information, you say, to the Germans?”

“Yes.”

“What made you say anything at all? Was it because you had been threatened, or why?”

“I do not really know.”

“You could have said nothing of course, could you not?”

“Yes.”

“Did you think it was a halfway house to give them false information, is that your idea?”

“Yes, I should say it was.”

“And at any rate it would put off the shooting for some time, is that the idea?”

“I was just trying to be optimistic.”

Hunt picked away at Seymour’s claim to have lied to the Germans, arguing that if the information he gave had failed to produce results and Schneider had suspected he was being fed false information, then Seymour would surely have been killed.

“You say what you told the Germans was untrue about the landing lights…did nobody come to you and tell you they had tried the information that you had given and they had no luck in capturing parachute troops?”

“No, nobody came to see me at all.”

Hunt stopped just short of the outright accusation that Seymour had willingly and knowingly collaborated with the enemy and saved his own skin by revealing everything to Schneider. “You have given the picture of a man interrogating you who really is not using threats to you at all,” Hunt remarked darkly.

It would be morally obtuse to rely on the testimony of a Gestapo officer facing the hangman’s noose. Schneider had every reason to divert guilt onto Seymour. Perhaps the young wireless operator really had fought the lone battle he described, and then cleverly passed false information to the Germans while keeping silent about the military details he knew. But the prosecutor plainly did not think so, and nor did Seymour’s surviving comrades in arms. “His value as a witness was doubtful,” said the intelligence officer investigating the deaths of SAS personnel after the war. Druce, as usual, was blunter: “We wrote Seymour off as a traitor.”

Treachery is an accusation that comes easily to those looking back. Seymour had exhibited bravery of a high order by volunteering for Operation Loyton and parachuting into the Vosges. But when the moment came to choose between resistance and death, or collaboration and survival, he seems to have chosen the more human and less heroic path. Everyone likes to believe they would not have done the same, but very few will ever put themselves in the situation where such a choice might arise. Seymour did.

—

In their absence, the men of the SAS had become, suddenly and rather uncomfortably, famous. Hitherto, almost total secrecy had surrounded the brigade, in part for reasons of operational security, but also because SAS’s unorthodox activities still carried, for some, a whiff of disrepute. In the summer of 1944, commanders were given formal permission to speak about their operations for the first time. The British press discovered the SAS, and had a field day: “Britain’s most romantic, most daring, and most secret army”; “Hush-hush men at Rommel’s back”; “Ghost Army paved the way for the Allies.” Some of the more traditional military figures might still consider SAS operations unsporting, but the public most certainly did not. Languishing in Colditz, Stirling had no idea that back in Britain he was being hailed as the pioneer of “a kind of Robin Hood system of operations.” The hints of roguish derring-do, combined with a distinct lack of hard detail, created a hunger for SAS stories that has never abated: “One day their exploits in France will be told, but for the moment they must remain secret.”

—

On October 8, 1944, General Dwight Eisenhower wrote a letter to the commander of SAS troops, Brigadier McLeod, sending congratulations “to all ranks of the Special Air Service Brigade on the contribution which they have made to the success of the Allied Expeditionary Force.”

The ruthlessness with which the enemy have attacked Special Air Service troops has been an indication of the injury which you were able to cause to the German armed forces both by your own efforts and by the information which you gave of German dispositions and movements. Many Special Air Service troops are still behind enemy lines; others are being reformed for new tasks. To all of them I say “Well done, and good luck.”

Those new tasks would include a return to Italy, taking the war on to German soil, and warfare on a scale of savagery the SAS had never encountered before, as Hitler’s Reich entered its death throes in a welter of blood and cruelty.

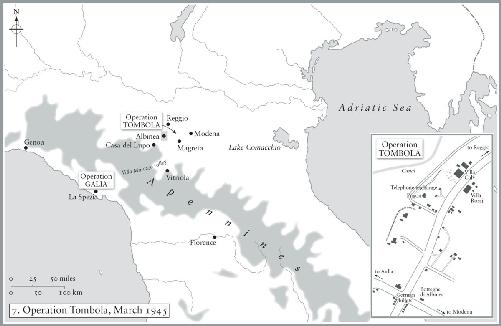

On the afternoon of March 26, 1945, two young Italian women cycled into the little village of Albinea, south of Reggio. Usually a drowsy backwater, Albinea that day was a scene of considerable bustle. The German LI Corps had set up its headquarters in the town, some twenty miles north of the last line of German retreat running along the ridge of the Apennines. German officers had commandeered and taken up residence in Albinea’s two largest buildings: the grander Villa Rossi, on the east side of the main road, was the headquarters of the corps commander, while Villa Calvi, on the opposite side of the road, surrounded by trees, housed the German chief of staff and bureaucracy. Four sentries were posted outside each of the villas, checking the papers of everyone who entered. Six machine-gun posts had been erected behind sandbag ramparts around the village, and an eight-strong German patrol marched up and down the main street. The LI Corps had dug in for a long stay.

The two women, dressed in Italian peasant clothes, attracted no attention whatever. After half an hour spent discreetly observing the activity surrounding the divisional headquarters and flirting with the sentries, they headed back down the road in the direction they had come.

An hour later they reached Casa del Lupo, a farm set back from the road with a large shed that usually housed oxen and now contained one of the oddest units ever assembled under SAS command: twenty British soldiers, forty Italian partisans, and some sixty Russians, deserters from the German army and escaped prisoners of war led by a swashbuckling Russian lieutenant. Their number also included a Scottish bagpiper, dressed in a kilt.