Roosevelt (107 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

People in northern Virginia and Washington felt they had never known such a lovely spring. On the warm and windless morning of Saturday, April 14, the lilacs and azaleas were in full bloom. The funeral train rolled through woods spattered with showers of dogwood, crossed the Potomac, and pulled into Union Station. Thousands waited outside in the plaza, as they had so often before. Anna, Elliott, and Elliott’s wife entered the rear car; President Truman and his Cabinet followed. Then the soldier’s funeral procession began—armored troops, truck-borne infantry, the Marine band, a battalion of Annapolis midshipmen, the Navy band, WAC’s, WAVES, SPAR’s, women Marines, then a small, black-draped caisson carrying the coffin, drawn by six white horses, with a seventh serving as outrider. Army bombers thundered overhead.

“It was a processional of terrible simplicity and a march too solemn for tears,” William S. White wrote, “except here and there where someone wept alone. It was a march, for all its restrained and slight military display, characterized not by this or by the thousands of flags that hung limply everywhere but by a mass attitude of unuttered, unmistakable prayer.”

In front of the White House the coffin was lifted from the caisson while the national anthem was played, carried up the front steps, and wheeled down a long red carpet to the East Room. Here where Lincoln had lain, banks of lilies covered the walls. The President, Cabinet members, Supreme Court justices, labor leaders, diplomats, politicians, agency heads crowded into the room and

spilled over into the Blue Room. At the close of his prayer, Bishop Dun paused and quoted from the First Inaugural: “…Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself….” Eleanor Roosevelt rose and left the room; then the others filed out. Later, upstairs, she came into Anna’s room, in anguish. She had heard in Warm Springs, from a relative, about Lucy Rutherfurd’s visits; she had heard that Lucy had been with her husband when he died. Her daughter must have known of this; why had she not told her? Mother and daughter confronted each other tensely. Then, as always, Eleanor Roosevelt steadied herself. She returned to the East Room, had the casket opened, and dropped in some flowers. Then the casket was sealed for good. Later in the evening the funeral cortege went back to Union Station. Crowds still lined the avenues. The presidential train, with seventeen cars filled with officials and politicians, pulled out before midnight.

The train had brought Roosevelt’s body up through Virginia, the land of Washington and Jefferson; now, from the capital all the way to Hyde Park, he would be following the route of Abraham Lincoln’s last journey, and people would be thinking of the strange parallels between the two—the sudden, unbelievable deaths, the end for each coming in the final weeks of terrible wars, the same April dates—and of things that seemed to be more than coincidence. Both men had been perplexing combinations of caution and courage, of practicality and principle; both had taken their countries into war only after

faits accomplis

had allowed it; both had acted for black Americans only under great pressure.

Through the long night, under weeping clouds, the train moved north, through Baltimore to Wilmington to Philadelphia. And everywhere it was as it had been eighty years before:

“When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d….

With the waiting depot, the arriving

coffin, and the somber faces,

With dirges through the night, with the

thousand voices rising strong and solemn….”

After all his delays and evasions, Lincoln had won standing as a world hero, through emancipation and victory and martyrdom, but Roosevelt—what kind of hero was Roosevelt? Some close observers felt that people exaggerated Roosevelt’s political courage. Clare Boothe Luce remarked that every great leader had his typical gesture—Hitler the upraised arm, Churchill the V sign. Roosevelt? She wet her index finger and held it up. Many others noted

Roosevelt’s cautiousness, even timidity. Instead of appealing to the people directly on great developing issues and taking clear and forthright action to anticipate emergencies, he typically allowed problems to fester and come to a head in the form of dramatic issues before acting with decision. He often took bold positions only to retreat from them in subsequent words or actions. He seemed unduly sensitive to both congressional and public opinion; he used public-opinion polls much more systematically than was realized at the time, even to the point one time of polling people on the question of who should succeed Knox as Secretary of the Navy (Stassen lost). His arresting speeches gave him a reputation as the fearless leader, but he spent far more time feinting and parrying in everyday politics than in mobilizing the country behind crucial decisions.

Around 2:00

A.M.

the train crossed into New Jersey, the state where Woodrow Wilson had plunged into politics as a reformer, while young Roosevelt, impressed, watched from Hyde Park and Albany. Old Wilsonians later had compared Roosevelt unfavorably to the great idealist who had gone down fighting for his dream. Roosevelt, too, had watched that performance—had been part of it—and had drawn his conclusions from it. Sherwood remembered him sitting at the end of the long table in the Cabinet room and looking up at the portrait of his onetime chief over the mantelpiece; the tragedy of Wilson, Sherwood said, was always somewhere within the rim of his consciousness.

“The tragedy of Wilson…” There were some who said that this was merely a personal tragedy for the man and a temporary tragedy for the nation and the world, that the prophetic warnings of the great crusader had been vindicated so dramatically by the collapse of the balance of power twenty years later that Wilson’s very defeat had made possible American commitment to a new international organization. Roosevelt did not share this view. He had no wish to be a martyr, to be vindicated only a generation later. He believed in moving on a wide, short front, pushing ahead here, retreating there, temporizing elsewhere, moving audaciously only when forces were leaning his way, so that one quick stroke—perhaps only a symbolic stroke, like a speech—would start in his direction the movement of press and public opinion, of Congress, his own administration, foreign peoples and governments. All this he could do only from a position of power, from the pulpit of the presidency. To gain power meant winning elections; and to win elections required endless concessions to expediency and compromises with his own ideals.

Projected onto the international plane this strategy demanded of Roosevelt not only the usual expediency and opportunism but

also a willingness to compromise with men and forces antagonistic to the ideals of Endicott Peabody and Woodrow Wilson. Again and again, self-consciously and indeed with bravado, he “walked with the devil” of the far left or far right, in his deals with Darlan and Badoglio, his toleration of Franco, his concessions to Stalin. Yet this self-confessed, if temporary, companion of Satan was also a Christian soldier striving for principles of democracy and freedom that he set forth with unsurpassed eloquence and persistence.

Did he then not “mean it”? So Roosevelt’s enemies charged. It was all a trick, they said, to bamboozle the American people or their allies, to perpetuate himself in power, or to achieve some other sinister purpose. But it seems clear that Roosevelt did mean it, if meaning it is defined as intensity of personal conviction rooted in an ideological commitment. “Oh—he sometimes tries to appear tough and cynical and flippant, but that’s an act he likes to put on, especially at press conferences,” Hopkins said to Sherwood. “He wants to make the boys think he’s hard-boiled. Maybe he fools some of them, now and then—but don’t ever let him fool you, or you won’t be any use to him. You can see the real Roosevelt when he comes out with something like the Four Freedoms. And don’t get the idea that those are only catch phrases.

He believes them….”

Roosevelt, like Lincoln and Wilson, died fighting for his ideals. It might have been more dramatic if he had been assassinated by an ideological foe or had been stricken during a speech. But his decisions to aid Britain and Russia, his daring to take a position before the 1944 election against the Senate having direct power over America’s peace-enforcing efforts in the proposed Council of the United Nations, his long, exhausting trips to Teheran and Yalta, his patient efforts to win Stalin’s personal friendship, his willingness to go out on a limb in his belief that the United States and the Soviet Union could work together in the postwar world—all this testified to the depth of his conviction.

Yet he could believe with equal conviction that his prime duty was to defend his nation’s interests, safeguard its youth, win the war as quickly as possible, protect its postwar economy. With his unconquerable optimism he felt that he could do both things—pursue global ideals and national

Realpolitik—

simultaneously. So he tried to win Soviet friendship and confidence at the same time he saved American lives by consenting to the delay in the cross-channel invasion, thus letting the Red Army bleed. He paid tribute to the brotherly spirit of global science just before he died even while he was withholding atomic information from his partners the Russians. He wanted to unite liberal Democrats and internationalist Republicans in one progressive party but he never did the spadework or took the personal political risks that such a strategy required. He yearned to help Indians and other Asiatic

peoples gain their independence, but not at the risk of disrupting his military coalition with Britain and other Atlantic nations with colonial possessions in Asia. He ardently hoped to bring a strong, united, and democratic China into the Big Four, but he refused to apply to Chungking the military resources and political pressure necessary to arrest the dry rot in that country. Above all, he wanted to build a strong postwar international organization, but he dared not surrender his country’s substantive veto in the Council over peace-keeping, and as a practical matter he seemed more committed to Big Four, great-power peace-keeping than he did to a federation acting for the brotherhood of all mankind.

“I dream dreams but am, at the same time, an intensely practical person,” Roosevelt wrote to Smuts during the war. Both his dreams and his practicality were admirable; the problem lay in the relation between the two. He failed to work out the intermediary ends and means necessary to accomplish his purposes. Partly because of his disbelief in planning far ahead, partly because he elevated short-run goals over long-run, and always because of his experience and temperament, he did not fashion the structure of action—the full array of mutually consistent means, political, economic, psychological, military—necessary to realize his paramount ends.

So the more he preached his lofty ends and practiced his limited means, the more he reflected and encouraged the old habit of the American democracy to “praise the Lord—and keep your powder dry” and the more he widened the gap between popular expectations and actual possibilities. Not only did this derangement of ends and means lead to crushed hopes, disillusion, and cynicism at home, but it helped sow the seeds of the Cold War during World War II, as the Kremlin contrasted Roosevelt’s coalition rhetoric with his Atlantic First strategy and falsely suspected a bourgeois conspiracy to destroy Soviet Communism; and Indians and Chinese contrasted Roosevelt’s anticolonial words with his military concessions to colonial powers, and falsely inferred that he was an imperialist at heart and a hypocrite to boot.

Roosevelt’s critics attacked him as naïve, ignorant, amateurish in foreign affairs, but this man who had bested all his domestic enemies and most of his foreign was no innocent. His supreme difficulty lay not in his views as to what

was

—he had a Shakespearian appreciation of all the failings, vices, cruelties, and complexities of man—but of what

could be.

The last words he ever wrote, on the eve of his death, were the truest words he ever wrote. He had a strong and active faith, a huge and unprovable faith, in the possibilities of human understanding, trust, and love. He could say with Reinhold Niebuhr that love is the law of life even when people do not live by the law of love.

It was still dark when the train drew into Pennsylvania Station. New York had been alive with rumors that Jack Dempsey or Frank Sinatra or some other celebrity had died, too. At the time of Roosevelt’s funeral service in the White House, New York City news presses stopped rolling, radios went silent, subway trains came to a halt, police held up traffic. In Carnegie Hall the Boston Symphony Orchestra, under Serge Koussevitzky, played Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony. Roosevelt’s train paused for a time at the Mott Haven railroad yards in the Bronx, then moved across Hell Gate and up the New York Central lines on the east bank of the Hudson—the route that Roosevelt had taken so often before.

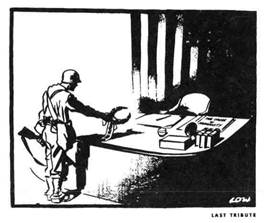

© Low, world copyright reserved, reprinted by permission of the Trustees of Sir David Low’s Estate and Lady Madeline Low

Newspapers were still reporting people’s reactions around the world—still reporting the shock, incredulity, and fear, but above all the sense of having lost a friend. In Moscow, black-bordered flags flew at half mast; Soviet newspapers, which invariably printed foreign news on the back page, published the news of Roosevelt’s death and his picture on page one. The theme of the editorials in Russia was friendship. Many Russians were seen weeping in the street. The

Court Circular

of Buckingham Palace broke ancient precedent by reporting the death of a chief of state not related

to the British ruling family; Roosevelt would have been pleased. In Chungking, a coolie read the wall newspapers, newly wet with shiny black ink, and turned away muttering

“Tai tsamsso liao”

(“It was too soon that he died”). “Your President is dead,” an Indian said to a passing GI, “a friend of poor….” Everywhere, noted Anne O’Hare McCormick, the refrain was “We have lost a friend.” It was this enormous fund of friendship on which Roosevelt expected to draw in carrying out his hopes for the postwar world. He expected to combine his friendships with captains and kings and his standing with masses of people with his political skills and the resources of his nation to strengthen the United Nations, maintain good relations with the Soviets, help the Chinese realize the Four Freedoms, discourage European colonialism in Asia and Africa. But all depended on his being on deck, being in the White House.