Roosevelt (66 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

Roosevelt’s personality and administrative methods encouraged this turbulence. He delegated power so loosely that bureaucrats found themselves entangled in lines of authority and stepping on one another’s toes. Despite his public disapproval of open brawls, Roosevelt actually tolerated them and sometimes even seemed to enjoy them. He saw some virtues in pitting bureaucrat against bureaucrat in a competitive struggle. The very nature of the New Deal programs with their improvised, experimental, and often contradictory qualities was another source of discord.

Criticism of Roosevelt’s administrative methods waxed during his second term. This criticism buttressed the demands of conservatives for “less government in business, and more business in government.” It was also a handy tool for congressmen bent on extending their own controls over the bureaucrats. But not all close students of the peculiar claims and needs of the American political system agreed with this criticism of Roosevelt as an administrator.

Again and again Roosevelt flouted the central rule of administration that the boss must co-ordinate the men and agencies under him—that he must make a “mesh of things.” But given the situation he faced, Roosevelt had good reasons for his disdain of copybook maxims. For one thing, too much emphasis on rigid organization and channels of responsibility and control might have suffocated the freshness and vitality he loved. His technique of fuzzy delegation, as Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., has said, “often provided a testing of initiative, competence and imagination which produced far better results than playing safe by the book.” Characteristically, Roosevelt himself took the burden of salving the aches and lacerations that resulted from his method of administration.

Disdaining abstract organization, Roosevelt looked at administration in terms of people. It was his sensitivity to people in all

their subtle shadings and complexities that stamped him as a genius in government. He impressed them by his incredible knowledge of small details of their job; he invigorated them by his readiness to back them up when the going got rough. Yet he was no sugary dispenser of lavish praise. One of his political lieutenants never got a comment on her work, but she was conscious of “warm, constant, and continuous support and a feeling that he liked me, had confidence in my ideas and was sometimes amused at my ‘goings-on’ as I was myself.”

One reason, then, for Roosevelt’s quixotic direction was that it quickened energies and incited ideas in musty offices of government. But there were other reasons.

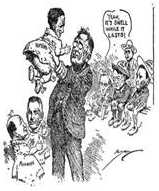

UPSIE DAISY

!,

March 28, 1935, C. K. Berryman, Washington

Star

Again and again Roosevelt put into the same office or job men who differed from each other in temperament and viewpoint. He gave Moley and later Welles important State Department tasks that overlapped those of Hull; he divided authority in the NRA between Hugh Johnson and the general counsel, Donald Richberg; he gave his current Secretary of War, Harry Woodring, an assistant secretary who was often at odds with his chief; he gave both Ickes and Hopkins control over public works, both Ickes and Wallace control over conservation and power, both Farley and a variety of other presidential politicians control over patronage and other political functions.

Roosevelt followed this seemingly weird procedure in part because it fell in naturally with his own personality. He disliked being completely committed to any one person. He enjoyed being at the center of attention and action, and the system made him the focus through which the main lines of action radiated. His facility at role-taking enabled him to deal separately with a variety of people at maximum advantage. His administrative methods tended to keep him well informed about administrative politics, too, for his bickering lieutenants were quick to bring him the various aspects of the situation.

The main reason for Roosevelt’s methods, however, involved a tenacious effort to keep control of the executive branch in the face of the centrifugal forces of the American political system. By establishing in an agency one power center that counteracted another, he made each official more dependent on White House support; the President in effect became the necessary ally and partner of each. He lessened bureaucratic tendencies toward self-aggrandizement; he curbed any attempt to gang up on him. He was, in effect, adapting the old method of divide and conquer to his own purposes.

The problem, from Roosevelt’s standpoint, was one of power rather than of narrow efficiency. His technique was curiously like that of Joseph Stalin, who used the overlapping delegation of function, a close student of his methods has said, to prevent “any single chain of command from making major decisions without confronting other arms of the state’s bureaucracy and thus bringing the issues into the open at a high level.” Roosevelt, like Stalin, was a political administrator in the sense that his first concern was power—albeit for very different ends.

How deliberate a policy was this on Roosevelt’s part? While he never formalized his highly personal methods of political administration and indeed ignored all abstract formulations of administrative problems, he probably was well aware of the justification of his methods in terms of his need to keep control of his establishment. Certainly he did not embrace unorthodox managerial techniques out of ignorance of orthodox ones. His navy and gubernatorial experience had given him a close understanding of basic management problems. His recommendations to Congress for administrative reorganization were right out of the copybook, as was his request, never granted, for the right of item veto over appropriations. Many of his subordinates came to respect his methods even while they were disconcerted by them. Harold Smith, who became budget director in 1939, found the President an erratic administrator. But years later, as the size and shape of Roosevelt’s job fell into better perspective. Smith told Robert Sherwood that

Roosevelt may have been one of history’s greatest administrative geniuses. “He was a real

artist

in government,” Smith concluded.

Yet a final estimate of Roosevelt’s administrative role must also include the enormous amount of wasted energy, delays, and above all the attrition of Roosevelt’s programs—especially the recovery program—caused by his methods. Good direction not only stimulates the ideas and energies of men; it also brings them into constructive harmony. What then can be said about Roosevelt’s toleration of incessant tension and friction among his lieutenants? Certainly the main effect of this intramural sharpshooting was more destructive than constructive. Certainly Ickes’ neurotic fight to wrest Forestry from Wallace during the reorganization battle was an example of wasted energies with no gain. That the New Deal often faltered in execution the President himself recognized. If, as has been said, the only genuine test of efficiency is survival, the Roosevelt recession, the continuing unemployment of 1939, and the bleeding of the President’s recovery proposals in 1939 raise a serious question about the administrative adequacy of his direction.

Inevitably Roosevelt’s practices produced hurt and bewilderment among his subordinates. “You are a wonderful person but you are one of the most difficult men to work with that I have ever known,” Ickes blurted out on one occasion.

“Because I get too hard at times?” Roosevelt asked.

“No, you never get too hard but you won’t talk frankly even with people who are loyal to you and of whose loyalty you are fully convinced. You keep your cards close up against your belly.…” If the President would confide in his advisers, Ickes went on, their advice would prevent him from making mistakes. Roosevelt took the criticism with good humor—but he did not change his methods.

On another occasion Democratic politicians were pressing Roosevelt to appoint a member of the Democratic National Committee as a federal judge, while the Justice Department was backing a government attorney. The pushing and hauling had reached a pitch when the President summoned representatives of both sides to the White House. They stated their cases.

“I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,” Roosevelt said. “I’m not going to take either man.” He named his choice. “Have either of you ever heard of him?” Neither had.

“Well,” the President went on. “His father was a remarkable man. Once the old man was sitting on his yacht and a big wave swept him off. Then another big wave came along and swept him back on. A remarkable man!” And that was all the explanation his visitors ever got—but Roosevelt’s appointment turned out to be an excellent one.

As an artist in government Roosevelt worked with the materials

at hand. The materials were not, of course, adequate. A final evaluation of Roosevelt as administrator must turn on his capacity to devise new materials out of which to fashion an administrative leadership that could stimulate men while keeping them in harness. In the end his capacity for effective administrative leadership turned on his capacity for creative political leadership.

The New Deal, wrote historian Walter Millis toward the end of 1938, “has been reduced to a movement with no program, with no effective political organization, with no vast popular party strength behind it, and with no candidate.” The passage of time has not invalidated this judgment. But it has sharpened the question: Why did the most gifted campaigner of his time receive and deserve this estimate only two years after the greatest election triumph in recent American history?

The answer lay partly in the kind of political tactics Roosevelt had used ever since the time he started campaigning for president. In 1931 and 1932, he had, like any ambitious politician, tried to win over Democratic leaders and groups that embraced a great variety of attitudes and interests. Since the Democratic party was deeply divided among its sectional and ideological splinter groups, Roosevelt began the presidential campaign of 1932 with a mixed and ill-assorted group backing. Hoover’s unpopularity with many elements in his own party brought various Republican and independent groups to Roosevelt’s support. Inevitably the mandate of 1932 was a highly uncertain one, except that the new President must do something—anything—to cope with the Depression.

Responding to the crisis, Roosevelt assumed in his magnificent way the role of leader of all the people. Playing down his party support he mediated among a host of conflicting interest groups, political leaders, and ideological proponents. During the crisis atmosphere of 1933 his broker leadership worked. He won enormous popularity, he put through his crisis program, he restored the morale of the whole nation. The congressional elections of 1934 were less a tribute to the Democratic party than a testament of the President’s wide support.

Then his ill-assorted following began to unravel at the edges. The right wing rebelled, labor erupted, Huey Long and others stepped up their harrying attacks. As a result of these political developments, the cancellation of part of the New Deal by the courts, and the need to put through the waiting reform bills, Roosevelt made a huge, sudden, and unplanned shift leftward. The shift put him in the role of leader of a great, though teeming and

amorphous, coalition of center and liberal groups; it left him, in short, as party chief. From mid-1935 to about the end of 1938 Roosevelt deserted his role as broker among all groups and assumed the role of a party leader commanding his Grand Coalition of the center and left.

This role, too, the President played magnificently, most notably in the closing days of the 1936 campaign. During 1937 he spoke often of Jefferson and Jackson and of other great presidents who, he said, had served as great leaders of popular majorities. During 1938 he tried to perfect the Democratic party as an instrument of a popular majority. But in the end the effort failed—in the court fight, the defeat of effective recovery measures, and the party purge.

That failure had many causes. The American constitutional system had been devised to prevent easy capture of the government by popular majorities. The recovery of the mid-1930’s not only made the whole country more confident of itself and less dependent on the leader in the White House, but it strengthened and emboldened a host of interest groups and leaders, who soon were pushing beyond the limits of New Deal policy and of Roosevelt’s leadership. Too, the party system could not easily be reformed or modernized, and the anti-third-term custom led to expectations that Roosevelt was nearing the end of his political power. But the failure also stemmed from Roosevelt’s limitations as a political strategist.

The trouble was that Roosevelt had assumed his role as party or majority leader not as part of a deliberate, planned political strategy but in response to a conjunction of immediate developments. As majority leader he relied on his personal popularity, on his

charisma

or warm emotional appeal. He did not try to build up a solid, organized mass base for the extended New Deal that he projected in the inaugural speech of 1937. Lacking such a mass base, he could not establish a rank-and-file majority group in Congress to push through his program. Hence the court fight ended as a congressional fight in which the President had too few reserve forces to throw into the battle.