Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic (53 page)

Read Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic Online

Authors: Tom Holland

Hypocrisy of an Olympian order, of course, but Romulus’ people were no longer in a condition much to care. Citizens now imagined their doom inexorable.

What does the bloodthirsty passage of time not leech away?

Our parents’ generation, worse than their parents

’,Has given birth to us, worse yet – and soon

We will have children still more depraved

.

28

This was a pessimism bred of more than war-weariness. The old certainties of what it meant to be a Roman had been poisoned,

and a confused and frightened people despaired of what had once bound them together: their honour, their love of glory, their military ardour. Freedom had betrayed them. The Republic had lost its liberty, but worse, it had lost its soul. Or so the Romans feared.

The challenge – and the great opportunity – for Augustus was to persuade them of the opposite. Do that and the foundations of his regime would be secure. A citizen who could restore to his fellows not only peace, but also their customs, their past and their pride would rank as august indeed. But he could not do it simply by legislating, ‘for what use are empty laws without traditions to animate them?’

29

Decrees on their own would not resurrect the Republic. Only the Roman people, by proving themselves worthy of Augustus’ labours, could do that – and therein lay the genius and the greatness of the policy. The new era could be cast as a moral challenge of the kind that the Romans had so often faced – and risen to triumphantly – in the past. Augustus, claiming no more authority than was due to him by virtue of his achievements and prestige, summoned his countrymen to share with him the heroic task of revitalising the Republic. He encouraged them, in short, to feel like citizens again.

And the programme was funded, as was traditional, with the gold of the defeated. The realisation of Augustus’ dreams was to be paid for, fittingly, out of the ruin of Cleopatra’s. In 29

BC

Octavian had returned to Rome from the East with the fabled treasure of the Ptolemies in his cargo-holds – and had immediately begun spending it. Huge tranches of land were bought up, in Italy and throughout the provinces, so that Augustus would never again have to commit the terrible crime of his youth: settling his veterans on confiscated property. Nothing had caused more misery and dislocation, and nothing had struck more brutally at the Romans’ sense of themselves. Now, at enormous expense, Augustus worked

to expiate his offence. ‘The assurance of every citizen’s property rights’ was to be an enduring slogan of the new regime, and one that did much to underpin its widespread popularity. To the Romans, security of tenure was a moral as much as a social or economic good. Those who benefited from its return saw it as hailing nothing less than a new golden age: ‘cultivation restored to the fields, respect to what is sacred, freedom from anxiety to mankind’.

30

Yet this golden age would impose duties on those who enjoyed it. Unlike the Utopia described by Virgil, it would not be a paradise purged of toil and danger. That would hardly serve to breed hardy citizens. Augustus had not invested the treasure of the Ptolemies merely to encourage his countrymen to lounge around like effeminate Orientals. Instead, his fantasy was the old one of all Roman reformers: to renew the rugged virtues of the ancient peasantry, to bring the Republic back to basics. It struck a deep chord, for this was the raw stuff of Roman myth: nostalgia for a venerated past, yes, but simultaneously a spirit harsh and unsentimental, the same that had forged generations of steel-hard citizens and carried the Republic’s standards to the limits of the world. ‘Back-breaking labour, and the urgings of tough poverty – these can conquer anything!’

31

So Virgil had written, while Octavian, in the East, was defeating Cleopatra and bringing an end to the civil wars. No vision of an indolent paradise now, but something more ambiguous, challenging – and, by Roman lights, worthwhile. Honour, in the Republic, had never been a goal in itself, only a means to an infinite end. And what was true of her citizens, naturally, was also true of Rome herself. Struggle had been her existence, and the defiance of disaster. For the generation that had lived through the civil wars, this was the consolation that history gave them. Out of calamity could come greatness. Out of dispossession could come the renewal of a civilised order.

For what was Caesar Augustus himself, after all, if not the heir of a refugee? Long before there had been such a city as Rome, Prince Aeneas, the son of Venus, the ancestor of the Julian clan, had fled burning Troy and voyaged with his small fleet to Italy, his quest, given him by Jupiter, to make a new beginning. It was from Aeneas and his Trojans that the Roman people had eventually sprung, and in their souls it could be imagined they still retained something of the wanderer. Not to be content with what they had, but always to strive and fight for more, this had been the destiny of the Republic’s citizens – and it gave to Augustus and his mission a time-hallowed glow.

In the Romans’ beginning was their end. In 29

BC

, the same year that Octavian returned from the East to push forward his programme of regeneration, Virgil started a poem on the theme of Aeneas. This was to become the great epic of the Roman people, an exploration both of their primordial roots and of their recent history. Like spectres, famous names out of the future haunt the vision of the Trojan hero: Caesar Augustus, naturally, ‘son of a god, who brings back the age of gold’,

32

but others too – Catiline, ‘trembling at the faces of the Furies’, and Cato, ‘giving laws to the just’.

33

When Aeneas, shipwrecked off the African coast, neglects his god-given duties to the future of Rome and dallies instead with Dido, the Queen of Carthage, the reader is troubled by knowing what will happen to the Trojan’s descendants, Julius Caesar and Antony; Carthage shimmers and elides with Alexandria; Dido with Cleopatra, a second fatal queen. What is gone and what is to come, both cast their shadows, one on the other, meeting, merging, separating again. When Aeneas sails up the Tiber, cattle low in the field that, a thousand years hence, will be the site of the Forum of Augustus’ Rome.

To the Romans themselves, who remained a conservative people despite all the upheavals of repeated civil wars, there was

nothing startling about the perception that the past might shadow the present. The unique achievement of Augustus, however, was the brilliance with which he colonised both. His claim to be restoring their lost moral greatness to them stirred in the Romans deep sensibilities and imaginings that at their profoundest could inspire a Virgil, and make their landscape once again a sacred and myth-haunted place. But these yearnings also served other, more programmatic purposes. They encouraged veterans, for instance, to remain on their farms and not come endlessly flocking to Rome; to be content with their lot, leaving their swords to rust in the lofts of their barns. And over the vast tracts of the countryside that remained the property of agri-business, worked by chain-gangs of slaves, they cast a veil woven of fantasy.

What is happiness? – opting out of the rat race

,Just like the ancient race of men

,Tilling ancestral fields with your own team of oxen

,Spared the horror of overdrafts

,Not a soldier, blood pumping at the fierce trumpet

,Not trembling at the angry sea.

34

So wrote Virgil’s friend Horace, with delicate irony, for he perfectly appreciated that his vision of the good life bore little relation to the realities of existence in the countryside. Yet it was no less precious to him for that. Horace had fought on the losing side in the civil wars, running away ingloriously from Philippi, and returning to Italy to find his father’s farm confiscated. Like his political loyalties, his dreams of a modest villa, of a life lived close to the land, were bred of nostalgia, no matter how self-mockingly expressed. Augustus, who never held Horace’s youthful indiscretions against him, offered the poet friendship and made an investment in his dreams. Even as the new regime was parcelling

out the huge estates of fallen Antonians to its supporters, it was also subsidising Horace in an idyllic existence outside Rome, complete with garden, spring and little wood. Horace himself was too subtle, too independent, to be bought as a propagandist, but crude propaganda was not what Augustus wanted from him, nor from Virgil. For generations Rome’s leading citizens had been tortured by the need to choose between self-interest and traditional ideals. Augustus, with his genius for squaring circles, simply made himself the patron of both.

And he could do this because, like any star performer, he had the pick of roles he wanted. Only the reality could not be acknowledged: Augustus had no wish to end up murdered on the Senate House floor. Instead, with the willing collaboration of his fellow citizens, who flinched from staring the truth in the face, he veiled himself in robes garnered from the antique lumber-box of the Republic, refusing any magistracy not sanctioned by the past, and often not holding any magistracy at all. Authority, not office, was what counted: that mysterious quality that had given to Catulus or to Cato his prestige. ‘In all the qualities that make up a man,’ Cicero had once acknowledged, ‘M. Cato was first citizen.’

35

‘First citizen’ – ‘

princeps’:

Augustus let it be known that he could wish for no prouder title. The son of Julius Caesar was to be regarded as the heir of Cato too.

And he pulled it off. No wonder that Augustus boasted of his skills as an actor. Only a man with a supreme talent for dissimulation could have played such various parts so subtly – and with such success. On his signet-ring, the

princeps

carried the image of a sphinx – and throughout his career he posed his countrymen a riddle. The Romans were used to citizens who vaunted their power, who exulted in the brilliance and glamour of their greatness – but Augustus was different. The more his grip tightened on the state, the less he flaunted it. Paradox, of course, had always suffused the

Republic, and Augustus, insinuating himself into its heart, took on, chameleon-like, the same characteristic. The ambiguities and subtleties of civic life, its ambivalences and tensions, all were absorbed into the enigma of his own character and role. It was as though, in a crowning paradox, he had ended up as the Republic itself.

During his final illness, Augustus, by now a venerable seventy-five years old, asked his friends whether he had performed adequately ‘in the mime-show of life’.

36

That he had retained his hold on supreme power for more than forty years; that in all that time he had kept Rome, and the world with her, secure from civil war, claimed no special rank for himself that had not been sanctioned by the law, and had his legions stationed not around him but far away, among forests or deserts, on barbarous frontiers; that in the end he was dying not of dagger wounds, not at the base of an enemy’s statue, but peacefully in his bed: these were dazzling notices for any citizen to have. Yes, it could be reckoned that Augustus had put on a good show. After all, he had made himself the only star in town.

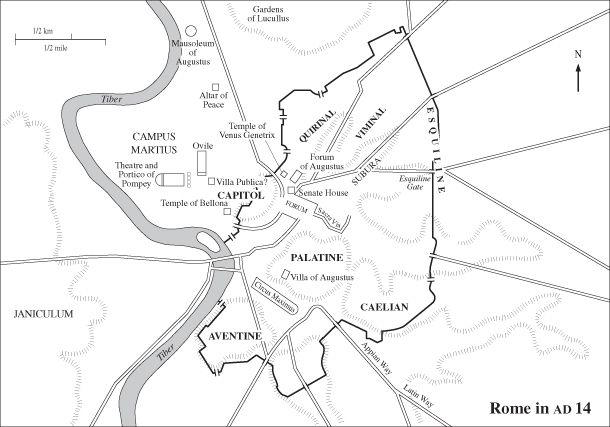

He died finally in the summer of

AD

14 in Nola – the same city from which Sulla, a century earlier, had begun his fateful march on Rome. Escorted back to the capital by senators, borne at night to prevent it turning putrid, the corpse of Augustus was finally burned, as Sulla’s had been, on a great pyre in the Campus Martius. The old dictator, if his ghost still haunted the plain, would have found the setting dramatically altered from the one he had known while alive. Carried reverently from the smouldering pyre, the ashes of Caesar Augustus were laid to rest in his mausoleum, a tomb so enormous that it had been built complete with its own public park: both its scale and its circular form, it was said, had been inspired by the tomb of Alexander the Great. The Campus Martius, once the training-ground of Roman youth, was now one

vast demonstration of the virtues of the

Princeps.

Of his magnanimity – for there, to the south, could still be seen Pompey’s theatre, the name and the trophies of Caesar’s enemy preserved by the grace of Caesar’s son. Of his benignity – for where once the Republic’s citizens had gathered to practise their weapons and be marshalled for war there now stood an Altar of Peace. And of his beneficence – for stretching even longer than Pompey’s theatre, a whole mile of gleaming porticoes, rose what had rapidly become, since its completion in 26

BC

, Rome’s premier entertainment venue, where Augustus had staged some of the most lavish spectacles ever seen in the city. Officially, this was the voting hall, the Ovile, an extravagant upgrading of the old wooden pens into marble. But it was rarely used for voting. Instead, where the Roman people had once gathered to elect their magistrates, gladiators now fought and bizarre monsters – giant serpents, for instance, almost ninety feet long – were displayed. And if there were no shows, then citizens could always flock there for the luxury shopping.