Sacre Bleu (15 page)

This was different. She was standing there in a beam of sunlight from the skylight, veritably glowing, as perfect and feminine as any statue in the Louvre, as ideal as any beauty obtained, any goddess imagined, by man.

Oh, she’d do. If I was being gnawed by wolves, before I’d bother to stop to shoo them off, she’d do.

“What are you doing, Lucien?” she said. “Open your eyes.”

“I’m trying to picture your desiccated scrotum,” said the painter.

“I don’t think anyone has ever said that to me before.”

“Dangling, dangling, almost there.”

“Where is your paint box? I don’t even see your paints.”

Lucien opened his eyes, and although he hadn’t gotten into a mindset of light and shadow quite yet, his erection had at least subsided. Perhaps he could work now. Better than those early days in Cormon’s when he was scolded. “Lessard, why have you drawn a nut sack on this model? You are drawing Venus, not a circus freak.”

“You said she was shape and line.”

“Are you serious? I am here only to teach serious painters.”

And then Toulouse-Lautrec would step up behind the master, adjust his

pince-nez

as if fine-tuning the focus, and say, “That

is

a serious nut sack on that Venus.”

“Indeed,” their friend Émile Bernard would say, stroking his mossy beard, “that is a nut sack of a most serious aspect.”

And around they’d pass the opinion, nodding and scrutinizing, until Cormon would either eject them all from class or storm out of the studio himself, leaving the poor model to break pose and inspect her nether parts, just in case.

Then Toulouse-Lautrec would say, “Monsieur Lessard, you are only to

think

about the scrotum to distract yourself, not actually draw it. I feel that the maestro will be even less open to discussing modern compositional theory now. To atone, you must now buy us all drinks.”

“I’m not going to be painting today,” Lucien said to Juliette. “It may take several days just to do the drawing.” He waved a sanguine crayon at the wide canvas he’d set up on two chairs from the bakery café, it being too large for any easel he owned.

“It is a very large canvas,” Juliette said. She lay down on the fainting lounge and propped herself up on her elbow. “I hope you are planning on taking a long time to paint this if you want me to grow into it. I’ll need pastries.”

Lucien glanced up at her, saw the mischievous smile. He liked that she was implying that she would stay around, that there was a future for them together, after she’d bolted before. He was tempted to make some ridiculous promise about taking care of her, knowing full well that the only way he could honestly make that promise was to put down his paintbrush forever and bake bread.

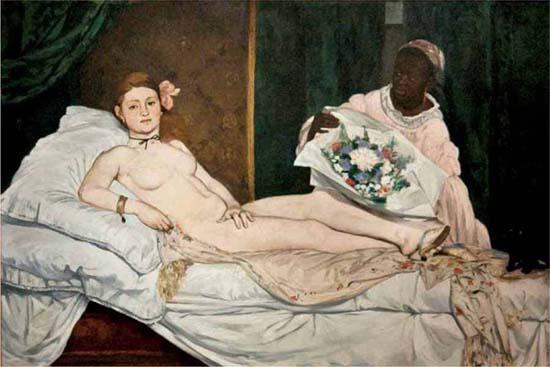

“Monsieur Monet told me once that great paintings are only achieved when the painter has great ambition. That’s why, he said, Manet’s

Luncheon in the Grass

and

Olympia

were great paintings.”

“Great

big

paintings,” she giggled.

They

were

large canvases. And Monet

had

attempted his own luncheon on the grass, a great, twenty-foot-long canvas that he dragged, rolled up, all over France with a pretty model named Camille Doncieux whom he’d met in the Batignolles and his friend Frédéric Bazille to pose for all the male figures. “But don’t let your ambition become too large too early, Lucien,” Monet had told him. “In case you have to sneak out on your hotel bill in the middle of the night with the canvas. Camille nearly broke her neck helping me carry that canvas through the streets of Honfleur in the dark.”

“How about like this?” Juliette said. She leaned back into the cushions, her hands behind her head, a knowing smile. “You can use Goya’s

Maja

pose. That’s what Manet started with.”

“For the love of God, she’s naked over there, aren’t any of you thinking about bonking her?”

The Nude Maja

—Francisco Goya, 1797

“Oh no,

ma chère,”

Lucien said. “Manet didn’t go to Madrid to see Goya’s

Maja

until after he painted

Olympia.

He didn’t know what she looked like.” Lucien had grown up on lectures on the famous paintings from Père Lessard; their stories were the fairy tales of his childhood.

“Not him, silly. The model knew.”

“You can use Goya’s

Maja

pose. That’s what Manet started with.”

Olympia

—Édouard Manet, 1863

What a completely disturbing thought. Olympia did look remarkably like Goya’s

Nude Maja,

regarding the viewer, daring him, and Manet clearly admired Goya, using Goya’s

Maja on the Balcony

as inspiration for his own painting of the Morisot family,

The Balcony,

and Goya’s war paintings from Napoleon’s invasion of Spain for his

Execution of Maximilian,

but those works were later, after Manet had gone to Spain and

seen

the Goyas. It couldn’t have been the model, Victorine. She was, well, she was like many models of the time, an uneducated, undowered girl who lived in the

demimonde,

the half world between prostitution and destitution. The model was like the brush, the paint, the linseed oil, the canvas. She was an instrument of the artist, not a contributor to the art.

“You know a lot about painting for a girl who works in a hat shop,” Lucien said.

“So, now you’ll paint me with only one brush?”

“No, I didn’t mean—”

“You know a lot about painting for a baker,” she said, the sparkle of a dare in her eyes.

Bitch.

“Hold that pose. No, bring your right arm down to your side.”

“Do it for me,” she pouted. “I don’t know how.”

“Just move, Juliette. Now, don’t move.”

And he began to sketch her image nearly life-size on the canvas. First roughing out her figure, then going back, filling in contours. He lost himself in the drawing, seeing only

form, line, light,

and

shadow,

and time slipped into those dimensions until she moved.

“What? No!” Lucien dropped his crayon on the seat of one of the chairs he was using for an easel.

She stood up, stretched, yawned, fluffed her breasts up a bit, which transported Lucien out of the land of line and shape, back to a small, sunlit room with a beautiful, naked girl whom he desperately wanted to make love to, and perhaps marry, but definitely and immediately bonk.

“I’m hungry and you’re not even painting.”

She started to gather her clothes from a chair by the door.

“I have to have the whole motif sketched out, Juliette. I’m not going to paint you in the storeroom of a bakery. The setting needs to be more grand.”

She stepped into her pantaloons and his heart sank.

“Does the

Maja

have a grand setting? Does

Olympia

have a grand setting, Lucien? Hmmm?”

And the chemise went over her head and her shoulders and the world became a dark and sad place for Lucien Lessard.

“Are you angry? Why are you angry?”

“I’m not angry. I’m tired. I’m hungry. I’m lonely.”

“Lonely? I’m right here.”

“Are you?”

“I am.”

He stepped up to her, took her in his arms, and kissed her. And off came the chemise, off came the pantaloons, then his shirt, then the rest, and they were on each other, on the fainting lounge, completely lost in one another. There may have been pounding on the door at one point, but they didn’t hear it and didn’t care. Where they were, no one else mattered. When, at last, she looked down from the lounge, at him, lying on his back on the floor, the light from the skylight had gone orange, and the sweat sheen on their bodies looked like slick fire.

“I have to go,” she said.

“Maybe I’ll be able to start painting tomorrow.”

“First thing in the morning then?”

“No, ten, maybe eleven. I have to make the bread.”

“I’m going.” She slid from the lounge and again gathered her clothes while he watched.

“Where are you living now?”

“A little place in the Batignolles. I share with some other shopgirls.”

“Don’t you have to work tomorrow?”

“The owner of my shop is understanding. He enjoys art.”

“Stay. Have dinner with me. Stay at my apartment. It’s closer than yours.”

“Tomorrow. I need to go. The day is gone.”

She was dressed now. He would have given a fortune, if he’d had it, to watch her pull her stockings up again. He sat up.

“Tomorrow,” she said again. She put her hand on his shoulder and kept him from rising, then kissed him on the forehead. “I’ll go out through the alley.”

“I love you,” he said.

“I know,” she said as she closed the door.

“W

ELL

?”

SAID THE

C

OLORMAN.

She put her parasol in a stand by the door and untied the wide ribbon that held on her hat, then set it gently on the hall tree. The apartment’s parlor was small but not shabby. A Louis XVI coffee table in gold leaf and marble sat before a mauve velvet divan. The Colorman sat in a carved walnut chair from the same period and looked like a malignant, twisted burl infecting the elegant wooden form.

“He didn’t paint,” she said.

“I need a painting. Since we lost the Dutchman’s picture, we need the color.”

“That was a waste. He’ll paint. He just hasn’t started yet.”

“I mixed colors for him. Greens and violets made with the blue, as well as the pure color. I put them in a nice wooden box.”

“I’ll give them to him tomorrow.”

“And make him paint.”

“I can’t make him paint. I can only make him

want

to paint.”

“We can’t have another perfectionist like that fucking Whistler. We need a painting, soon.”

“He needs to be handled gently. This one is special.”

“You always say that.”

“I do? Well, perhaps it’s true.”

“You smell of sex.”

“I know,” she said as she sat on the divan and began to unlace her shoes. “I need a bath. Where’s the maid?”

“Gone. She quit.”