Sacre Bleu (26 page)

Pissarro, who had been looking at the painting since Henri had entered, trying to keep his mind off the atrocious odor, said, “Rescue him? From what?”

“From her,” said Henri, nodding to the painting.

“Danger is not the first impression she inspires,” said Gachet.

“Not just her,” said Toulouse-Lautrec. “The Colorman, too.”

Now both Gachet and Pissarro looked to the diminutive painter.

“They are together,” said Lautrec.

“Vincent said something about a color man right before he died,” said Gachet. “I thought it was just delirium.”

“Vincent knew him,” said Henri. “A very specific color man. Small, brown, broken looking.”

“And this girl, Lucien’s model, is associated with him?” asked Pissarro.

“They live together in the Batignolles,” said Henri.

Pissarro looked to Gachet. “Do you think Lucien is strong enough to talk?”

Lucien studied Gachet’s eyes, which were large and always a bit doleful, as if he could see some sadness in the heart of everything.

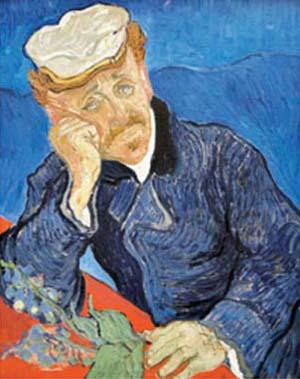

Portrait of Doctor Gachet

—Vincent van Gogh, 1890

R

ÉGINE FED

L

UCIEN BROTH AND A LITTLE BREAD—THE COLOR GRADUALLY

returned to his cheeks. Madame Lessard brought in a basin and shaved him with a straight razor while Pissarro and Dr. Gachet looked on. When she left the room, Dr. Gachet closed the door behind her and took a seat on the stool by Lucien’s bed. Pissarro and Toulouse-Lautrec stood by.

Lucien looked to each of them, then grimaced. “Good God, Henri, is that smell coming from you?”

“I was going to come right over as soon as I heard you were awake, but the girls insisted upon giving me a bath first. I sat vigil for you for a week, my friend.”

“One sits vigil

over

the dying, not ten blocks away, on a pile of whores, out of his mind on opium and absinthe.”

“Each grieves his own way, Lucien. And since you are going to survive, it appears that my method may have therapeutic benefits. But I will defer to the good doctor’s judgment.” Henri looked over his

pince-nez

at Gachet.

“No, I don’t think that’s the case,” said the doctor.

“My apologies, then, Lucien, you aren’t going to survive.”

Gachet was nonplussed. “That’s not what I was saying—”

“If not, may I have the new painting? It is your masterpiece.”

“It’s not finished,” said Lucien.

“Should we go?” Pissarro asked the doctor, gesturing to himself and Toulouse-Lautrec.

“No. I may need you two to help me diagnose Lucien’s trouble.”

“But we are painters—”

“And therefore somewhat useless,” said Lautrec.

The doctor held up his finger to stop him in his place. “You will see.” To his patient, he said, “Lucien, when you first woke up, you asked about Minette. You said ‘the blue’ and asked if it had taken her. What did you mean?”

Lucien tried to think, but there were things muddled up in his head. He remembered London, and seeing the Turners and Velázquez’s

Venus,

but he had never been to London. Everyone was sure of it but him. They said he’d been in the studio for days before they found him, and no one had seen him leave.

“I don’t know,” Lucien said. “Maybe it was a dream. I don’t remember. I just felt Minette, gone. Like it had just happened and something had taken her from me.”

“You asked if ‘

blue

’ had taken her,” said the doctor.

Lucien studied Gachet’s eyes, which were large and always a bit doleful, as if he could see some sadness at the heart of everything.

“That doesn’t make sense, does it?” said Lucien.

“The boy is tired,” said Pissarro. “Let’s let him rest.”

“Not to worry,” Gachet said. “But you don’t remember, do you? You don’t remember Minette being sick?”

“No,” said Lucien. He could feel the heartbreak of her loss, but he didn’t remember his first love falling ill. Only the arrow to the heart when they told him of her death. He could still feel it.

“And you don’t either?” Gachet said to Pissarro.

The painter shook his head and looked at his hands. “Perhaps it is a blessing.”

“Yet you both were there,” said the doctor. “I treated Minette for her fever. I remember, you were both there.”

“Yes,” said Pissarro. “I had done several paintings of Lucien, so I …” Pissarro lost his thought.

“Where are they?” asked the doctor.

“What?”

“Camille, I’ve seen nearly every painting you’ve done. I’ve never seen a portrait of Lucien.”

“I painted them. Three, maybe four. I was teaching him while I painted. Teaching my own son Lucien, as well. Ask him.”

Gachet looked to Lucien. “Do you remember those sessions?”

Lucien tried to remember. It had to have taken hours and hours of sitting still, back in a time when sitting still was a very difficult thing to do, yet all he could bring up was a sense of anxiety, rising to almost a panic from his core. “No. No, I don’t remember.”

“And you’ve never seen the paintings?”

“No.”

Pissarro grabbed his friend’s arm. “Gachet, what is this about? Minette died eighteen years ago.”

“I have lost memories, too,” said Toulouse-Lautrec. “And I know others, well, one other, a model. It’s the color. Isn’t it?”

“What

is the color?” said Pissarro, his grief turning to exasperation. “We don’t remember because of what color?”

“I don’t know, let us examine this.” Gachet patted Pissarro’s hand to reassure him. “This color man, have you had dealings with him, Camille? Specifically, back in the time when you were painting Lucien?”

Pissarro closed his eyes and nodded. “I remember such a man. Many years ago. He came to Lessard’s bakery the day Père Lessard was raffling off one of my paintings. I paid him no mind. He gave me a tube of paint to try. Ultramarine, I think. Yes, I remember seeing him.”

“Did you use the paint?”

“I don’t remember. I suppose I would have. Those were lean times. I couldn’t afford to let color go to waste.”

“And, Lucien,” said the doctor. “Do you remember this color man?”

Lucien shook his head. “I remember a pretty girl won the picture. I remember her dress, white with big blue bows.” Lucien looked away from Pissarro. “I remember wishing that Minette had a dress like that.”

“Margot,” said Pissarro. “I don’t remember her surname. She modeled for Renoir. His swing picture, and the big Moulin de la Galette picture.”

“I knew her,” said Gachet. “Renoir called me to Paris to treat her. Marguerite Legrand was her full name. Do you know if Renoir bought color from this color man?”

“Why?” asked Toulouse-Lautrec.

“Because he has had these lapses in memory,” said the doctor. “Whole months that he lost, as has Monet. I don’t know about Degas, or Sisley, or Berthe Morisot—the others among the Impressionists—but I know these Montmartre painters have all had these memory lapses.”

“And Vincent van Gogh as well?” said Henri.

“I’m beginning to think so,” said Gachet. “You know that oil color can contain chemicals that can harm you? The mercury in vermilion alone could drive a man to what is called the ‘hatter’s madness.’ We all know someone who has been poisoned by lead white. Chrome from chrome yellow, cadmium, arsenic, all elements of the colors you use. That’s why I’ve always discouraged my painter friends from painting with their fingers. Many of those chemicals can enter the body just through the skin.”

“And Vincent used to eat paint,” said Henri. “Lucien and I saw him do it at Cormon’s studio. The master scolded him for it.”

“Vincent could be … well … passionate,” said Lucien.

“A loon,” said Henri.

“But brilliant,” said Lucien.

“Absolutely brilliant,” agreed Lautrec.

Gachet looked to Pissarro. “You know how Gauguin was saying that he and van Gogh had fought in Arles? Vincent became so violent that he cut off a piece of his own ear. Gauguin was forced to return to Paris.”

“Van Gogh committed himself to a sanitarium after that, didn’t he?” said Pissarro.

Lucien sat up now. “Vincent was not well. Everyone knows that.”

“His brother said he has had spells for years,” said Toulouse-Lautrec.

“Vincent didn’t remember the fight,” said the doctor. “Not at all. He told me that he had no idea why Gauguin left Arles. He thought Gauguin had abandoned him over artistic differences.”

“Gauguin said he had fits of temper that he didn’t even remember the next day,” said Pissarro. “The lapses were more disturbing than the temper.”

“Drinking?” said Lucien. “Henri loses weeks at a time.”

“I prefer to think of them as

invested,

not lost,” said Toulouse-Lautrec.

“Gauguin said he hadn’t been drinking that day,” said the doctor. “He said that Vincent thought his distress had something to do with a blue painting he had made. He would only paint with blue color at night.”

Lucien and Pissarro looked at each other, their eyes widening.

“What?” asked Gachet, looking from the young painter to the older and back. “What, what, what?”

“I don’t know,” said Pissarro. “When I think of that time, I feel something terrible. Frightening. I can’t tell you what it is, but it seems to live just outside of my memory. Like a phantom face at a window.”

“Like the memory of a dog that’s been mistreated,” said Henri. “I mean, that is how I feel about the time I lost. I don’t understand what happened, but it frightens me.”

“Yes!” said Lucien. “As if the more I think about it, the more the memory runs away.”

“But it’s blue,” said Pissarro.

“Yes. Blue.” Lucien nodded.

Gachet stroked his beard and looked back and forth again, searching the painters’ faces for some hint of irony, amusement, or guile. There was none.

“Yes, there’s that, the blue,” said Henri. Then to the doctor, “What about hallucinations? Remembering things that never happened, maybe?”

“It could all be caused by something that this color man put in the paint. Even trace amounts from breathing fumes could have caused it. There are poisons so powerful that the amount you could put on the head of a pin could kill ten men.”

“And you feel that this is why Vincent killed himself? That he had bought color from this little color man?” asked Lucien.

“I’m not sure anymore,” said Dr. Gachet.

“Well,” said Henri, “you will be more assured soon. I’ve commissioned a scientist from the Académie to analyze color I bought from the Colorman. We should know any day.”

“That’s not what I meant,” said Gachet. “I mean, yes, he may have been under the influence of some chemical compound, but I’m not sure that Vincent killed himself.”

“But your wife said he confessed it when he came to your house,” said Pissarro. “He said, ‘This is my doing.’”

“That was enough for the constable, and at first, I didn’t question it. But think: who shoots himself in the chest, then walks a mile to the doctor? This is not the action of a man who wants to end his life.”