Sacre Bleu (35 page)

As the train’s brakes hissed and squealed and the great beast stopped, the Colorman noticed another man by the tracks, a slight fellow with a goatee, wearing a light gray plaid suit and hat that was entirely too fine for a stevedore or porter, and except for the Colorman, no one else was to be found this far down the tracks, away from the passenger platforms. The man in gray held a

pince-nez

and seemed to be trying to read the sides of the train cars.

“What are you looking for?” asked the Colorman.

“This is the train from Italy, I’m told,” said the man, eyeing Étienne’s boater hat suspiciously. “I’m expecting a shipment of colored ores, but I don’t know where to find it.”

“It’s probably that one,” said the Colorman, pointing to a train car he was sure it wasn’t. “You are a painter?”

“Yes. Georges Seurat is the name. My card.”

The Colorman looked at the card, then handed it to Étienne, who thought it tasted fine.

“You painted that big picture of the monkey in the park.”

“There was a very small monkey in a very large park.

Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

That painting was about placement of color.”

“I liked the monkey. You should buy your paints from a color man.”

“I work in pure hues,” said Seurat. “After Chevreul’s theory of mixing color in the eye, rather than on the canvas. Dots of complementary color placed next to each other cause an instinctual and emotional response in the mind of the viewer—a vibration, if you will. Something that can’t be achieved by color muddied on the palette. I need the colors as raw as can be.”

“That sounds like bullshit,” said the Colorman.

“Chevreul was a great scientist. The world’s premier color theorist,

and

he invented margarine.”

“Margarine? Ha! Butter with the flavor and color taken out. He’s a charlatan!”

“He’s dead.”

“So you see, then,” said the Colorman, thinking he had made his point by not being dead. “You should buy your pure color from a color man. Then you can have more time to paint.”

Seurat smiled then, and tapped his walking stick on the bricks. “You are a color man, I presume?”

“I am

the

Colorman,” said the Colorman. “Only the finest earths and minerals, no filler, mixed to order, in whatever medium you like. I like poppy oil. No yellowing. Like margarine. But if you want linseed or walnut oil, I have them.” The Colorman rapped his knuckles against the big wooden case strapped on Étienne’s back.

“Let me see,” said Seurat.

The Colorman wrestled the case off of Étienne’s back and opened it on the bricks. “I’m out of blue, but if you want, I’ll have some delivered to your studio.” The Colorman handed the painter a tube of Naples yellow.

“Very fine,” said Seurat, squeezing a worm’s-head length out of the tube and turning it to catch the light of the rising sun. “I think this will do. I wasn’t looking forward to grinding ores all day, anyway. What is your name?”

“I am the Colorman.”

“I understand, but your name? What do I call you?”

“The Colorman,” said the Colorman.

“But your surname?”

“Colorman.”

“I see. Like Carpenter or Cooper. An old family trade then? And your first name?”

“

The,

” said the Colorman.

“You are a very strange fellow, Monsieur Colorman.”

“You like to paint the women as well as the monkeys, right?” asked the Colorman, making a gesture that didn’t look at all like he was painting.

“You are a color man, I presume?”

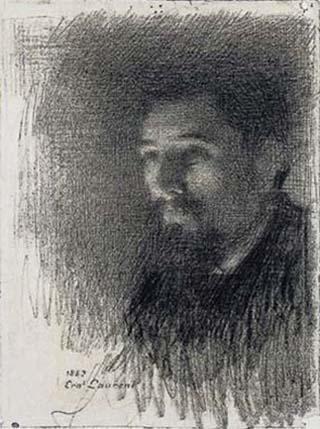

Georges Seurat

—Ernest Laurent, 1883

M

ÈRE

L

ESSARD PREPARED A BASKET OF BREAD AND PASTRIES FOR

Lucien to take with him to Giverny. “Give my warmest regards to Madame Monet and the children,” the matriarch said, tucking croissants into a nest of white tea towels. “And remind Monsieur Monet that he is a wastrel and a ne’er-do-well and to please stop by the bakery when he is in Paris.”

Régine stopped him at the bakery door and kissed his cheek. “I don’t think you should be going so soon, but I’m glad you’re not out looking for that horrible woman.”

“You are the only horrible woman allowed in my life,

chérie,

” he said, hugging his sister.

It was two hours on the train from Gare du Nord to Vernon, and during the ride Lucien sat near a young mother and her two little daughters, dressed as finely as fancy dolls, who were traveling to Rouen. He sketched them and chatted and laughed with them, and people who passed down the aisle of the train smiled at him and wished him good day, and generally, he thought that during his time locked away in the studio with Juliette he had developed some new form of magical charm, when in fact it was just that he and his basket smelled of freshly baked bread and people like that.

From the station at Vernon, he walked the two miles into the countryside to Giverny—less a village, really, than a collection of small farms that happened to perch together just off the river Seine. Monet’s place lay on a sunny rise above a grove of tall willows that had once been a marsh that the painter had converted into a water garden, with two wide lily ponds with an arched Japanese bridge at their intersection.

The house was a sturdy two-story of pink stucco with bright green shutters.

Madame Monet, who was, in fact, not yet Madame Monet, met Lucien at the door. Alice Hoschedé, a tall, elegant, dark-haired woman, her

chignon

now beginning to streak with gray, had been the wife of one of Monet’s patrons, a banker. She had now been with the painter for fifteen years, but they were not married. Monet had been living and painting commissions on the Hoschedés’ estate in the South when the banker suddenly fell into ruin and abandoned his family. Monet and his wife, Camille, invited Alice and her four children to live with them and their own two sons. Even long after Camille died, and she and Monet had become a couple, Alice, a devout Catholic, insisted they keep up the ruse that their relationship was platonic, and they still kept separate bedrooms.

“These are lovely, Lucien,” she said, accepting the basket of baked goods. A teenage daughter, Germaine, whisked them off to the kitchen. “Perhaps we can all share them for lunch,” said Alice. “Claude’s in the garden, painting.”

She led him through the house, the foyer and dining room of which were painted bright yellow. Nearly every wall was covered with framed Japanese prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige, with the odd Cézanne, Renoir, or Pissarro hung here and there among them as accents, or vice versa. Lucien peeked into a large parlor as they passed, the walls of which were lined floor to ceiling with Monet’s own work, but Lucien didn’t dare stop to lose himself in the master’s paintings as Alice was already on the back porch, presenting the garden with a wave, as if ushering an ascended soul into paradise.

“I think he’s back by the bridge today, Lucien.”

Lucien walked through the back garden, rows upon rows of blooming flowers, built from the ground up on trellises and tripods, so that from eye level to the lawn, there was nothing but color, roses and daisies and dahlias the size of dinner plates, all mixed wildly by color, if not species, so that there was no gradation, no pink next to a red, no lavender next to a violet, but contrast in size and color, blues over yellows, oranges nesting among purples, reds framed in greens. Lucien realized that from any window at the back of the house, one could look out upon nature’s palette exploding across the landscape. This was a garden designed by and for a painter, someone who loved color.

He came out of the mounds of color and into a cool grove of willow trees, and there, by the two mirror-calm lily ponds, he found Monet at his easel. Lucien made no attempt to approach in stealth; instead he shuffled his feet on the path and cleared his throat when he was still a good twenty meters away from the painter. Monet glanced quickly out from under the wide brim of his straw gardener’s hat, then went right back to applying paint to canvas. A finished painting leaned against the trunk of a nearby willow.

“So, Lucien, what brings you out to the country?” There was welcome and warmth in Monet’s voice, but he did not pause a second in his work. Lucien took no offense. Once, while painting his enormous

Luncheon on the Grass,

near the forest of Fontainebleau, with Frédéric Bazille and his beloved Camille as models, Monet had become so engrossed in his work that he’d neglected to notice a team of athletes had come to the field to practice, and so had been quite surprised when an errant discus shattered his ankle. Bazille had painted the scene of Monet convalescing, his leg in traction.

“I’m looking for a girl,” said Lucien.

“Paris has finally run out, then? Well, you could do worse than a girl from Normandy.”

Lucien watched the master laying down the color, the white and pink of the water lilies, the gray-green of the willows reflected on the surface of the water, the muted umber and slate blue of the sky in the water. Monet worked as if there was no thought process involved at all—his mind was simply the conduit to move color from his eye to the canvas, like the court stenographer who might transcribe a whole trial, every word going from his ear to the paper, yet remain unaware of what had transpired in the courtroom. Monet had trained himself to be a machine for the harvest of color. With brush in hand, he was no longer a man, a father, or a husband, but a device of singular purpose; he was, as he had always introduced himself,

the painter Monet.

“A particular girl,” said Lucien, “and to find her, I need to ask you about blue.”

“I hope you’re going to stay the week, then,” said Monet. “I’ll have Alice make up the guest room for you.”

“Not blue in general, Oncle. The blue you got from the Colorman.”

Monet stopped painting. There was no doubt in Lucien’s mind that he knew

which

Colorman.

“You have used his color, then?”

“I have.”

Monet turned on his stool now and pushed back the brim of his broad hat so he could look at Lucien. His long black beard was shot with gray, but his blue eyes burned with a fierce intensity that made Lucien feel as if he’d been stripped naked for some sort of examination. He had to look away.

Monet said, “I told you never to buy color from him.”

“No you didn’t. I didn’t remember ever seeing you with him until yesterday.”

Monet nodded. “That happens with the Colorman. Tell me.”

And so Lucien told Monet about Juliette and painting the blue nude, about Henri and Carmen, about their loss of memory, about the Professeur’s hypnotic trance and the phantom rain on their shoulders, about the death of Vincent van Gogh and the letter to Henri, how Vincent had been afraid of the Colorman and had tried to escape him by going to Arles.