Sacred Trash (17 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

[

K

]ept his yeast leavened from youth

L

eaving the issue to flow from his skin

And the Lord spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying: Speak unto the children of Israel and say unto them: When any man hath an issue out of his flesh, his issue is unclean

Despite the gall-eaten gaps that Davidson found in the manuscript—chasms, really, into which the words of our palimpsest long ago tumbled—several characteristic elements of Yannai’s poetry are immediately apparent, even in rough translation. Like many poems in this tradition, the hymn develops along an alphabetical acrostic. The final line of this opening section (

alef

through

lamed

in the Hebrew) leads into the first verse of the portion of the Torah read in the synagogue that week—in this case the

seder

(literally, the order) consisting of Leviticus 15:1–24, which treats the question of ritual purity, bodily discharge, and their attendant expiatory offerings—hardly the stuff of an inspiring lyricism. And yet, pus, too, was part of the early medieval Hebrew poetic process.

For it was incumbent upon the poet to make use of all the literary devices at his disposal in order to revive the experience of worship and wonder for his synagogue listeners. In this the

payyetan

was more mediating priest than scolding prophet.

However exotic or ingrown their compositions might seem by our own standards, at their best

payyetanim

produced real poetry, sometimes of a major sort. A vast allusive range; a feeling for dramatic possibility; an ability to extend scriptural narration; a varied repertoire of virtuoso musical strategies; and above all a developed sense of the tradition’s homiletical potential and the congregation’s hunger for the nourishment it might afford—all these were used to intensify the liturgical moment, to suck marrow from the seemingly dry bones of routinized prayer and to make it matter afresh, as the Mishna demanded: “Whosoever makes his prayer a fixed task,” it cautions, “his prayer is not a true supplication.” Other sources echo that call: “One’s prayer should be made new each day,” the Palestinian Talmud tells us, and “As new water flows from the well each hour, so Israel renews its song.” Extending that notion, other writers still have likened the

piyyutim

to angels, which—according to one midrash—are created by God for specific missions and vanish after completing them. Among certain Jewish communities of the East, from roughly the fifth through the end of the ninth centuries, it seems to have been considered disgraceful for a prayer leader to recite as part of the prayer service work that wasn’t his own.

Part three of Yannai’s long sequence based on the Levitical discussion of impurity contains the telltale acrostic “signature” that quietly, if precariously, copyrights the poet’s work. Though scholars before Davidson did not know it, and therefore did not

see

it, in Yannai’s

mahzor

this section always involves a four-line (or eight-hemistich) stanza, strung along the poet’s acrostic signature and concluding with an allusion to the first verse of the week’s

haftara,

or supplementary reading from the prophetical books (in this case, Hosea 6:1 and its notion of returning to God—

“who has torn, that he may heal”). While here, too, the manuscript is damaged, it is clear from the opening two lines and other

piyyutim

that the poet is employing full rhyme. This turns out to be an important literary discovery in its own right, as it represents the earliest known systematic employment of end rhyme in Hebrew, and one of the earliest in Western and Near Eastern literature.

Y

ou, Lord, who are faithful, our God and healing’s master—

your healing power is readied for all you summon with desire.

N

ow we return, [turning] to[ward] you, .................

as you give strength to our weakened hand … in yours

I

nto the rain of fresh blows ..... he ....................

and to the blow of ap.… [ah], blind wandering

I

nstill our remnants with wholeness … [our … ess],

Our father and healer, return to restore us.

In short—and notwithstanding the many lacunae in the manuscript—Davidson’s discovery of Yannai’s work made it possible for the first time to follow the elliptical, complex, and even symphonic development of this new kind of liturgical poem, which was known in Hebrew as a

kerova—

from the Aramaic

karova,

meaning cantor or prayer leader, who would draw

near

(

karov

) to the ark in the synagogue as he led the prayers or offered a sermon. Given the emphasis in so many

piyyutim

on the priestly dimension of worship, a powerful link was established in these hymns between poetry and prayer as a substitution for sacrifice (which was no longer possible after the destruction of the Temple in 70

C.E

.). The synagogue by this time had evolved from the house of study it was during the time of Ben Sira to a place of worship, a

mikdash me’at,

or little sanctuary. Like a cultic rite, and perhaps not unlike an opera, the poem’s ability to move an audience was, in large part, rooted in the spectacle and splendor of its structure. For while it posed a challenge, socially and intellectually, and in many ways involved a code that had to be cracked, this product of an age obsessed with endless renewal and

experience of the sublime in prayer was, apparently, sufficiently compelling to draw at least to certain synagogues large crowds—young and old—who would come, as one writer has put it, not with a prayer book they’d memorized, but anxious for a “fresh, living, and instructive word, one that would also console, as it provokes thought and serves as a spur to the imagination.”

And so, Sabbath morning after Sabbath morning, Yannai’s poems and others like them would be recited, or sung, ornamenting the opening benedictions of the liturgy’s central prayer—the

amida,

or standing prayer. (To a certain extent the

piyyutim

were originally intended to

replace

the standard liturgy.) The variegated and sometimes powerful Hebrew of the

kerovot

(plural) gave expression to virtually every aspect of the people’s life as a people (though not as individuals), and it led worshippers into the innermost layers of their faith’s foundational text. For these poems were devotional devices, spiritual machines made of words that were designed with a particular function in mind. And just as Burkitt had proposed that the Aquila hovering beneath Yannai’s Hebrew came from a synagogue copy of the Bible in Greek translation, so Davidson concluded that this collection of hymns, written over Aquila’s Greek, was also intended for synagogue use—most likely by the Palestinian Jewish community in Fustat, where these manuscripts were found.

The slim collection of some forty poems by Yannai that Davidson managed to bring quite elegantly between navy blue covers in 1919 was just the beginning. Alert now to the presence of a singular and major body of poetry among the some quarter million or so Geniza fragments held in libraries around the world, scholars turned their attention to the obvious—the upper writing, as it were, of the Geniza collection as a whole, where Hebrew liturgy (both hymns and prose prayers) constituted some 40

percent

of the cataloged documents, and they began rummaging. Davidson himself continued to identify and publish additional Yannai fragments as well, but the next serious advance in the field came, oddly, if indirectly, from the shelves of a German department store.

II

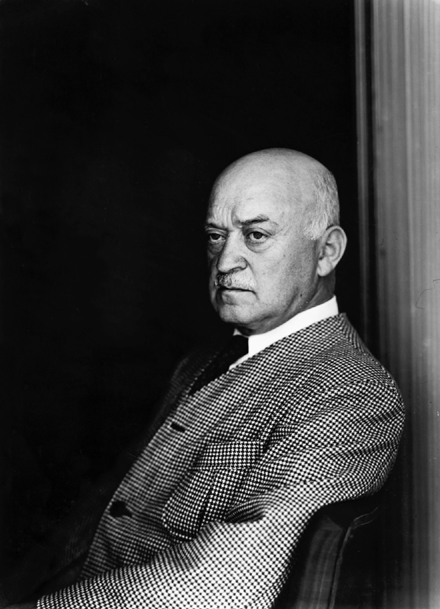

E

arly in 1928, the fifty-one-year-old self-made businessman and cultural patron Salman Schocken, looking a lot like a Roman patrician, traveled to Stuttgart to attend the opening of a new store, part of a chain he’d founded and operated throughout Germany. He had come a long way from his first job as a textile salesman based in Leipzig—that city of Bach’s cantatas—but he’d clearly taken a great deal with him. Schocken’s department stores were designed by some of the country’s finest architects, and the buildings themselves instantly became monuments of a kind. Implausible as it sounds, they were part of a broad, revolutionary vision that combined commerce and culture in an effort to bring “taste” of both a material and a spiritual sort to the hardworking members of German society at large. Just as he found new ways of making Bauhaus-inspired furniture, form-fitting cotton clothes, cologne, and the latest fashions in lingerie available to middle- and working-class people at affordable prices, so Schocken sought to disseminate the products of the humanist tradition to the masses—serious fiction, progressive cultural criticism, and both German and Jewish classics. By the time the Stuttgart store was completed, the Schocken chain was one of the largest in Europe.

While Schocken’s marketing strategies extended through all registers and regions of the country, the cultural renaissance he helped lead was initially limited to a small and radical circle of Jewish intellectuals he supported, including the Hebrew novelist and future Nobel Prize winner

S. Y. Agnon; the soon to be world-famous scholar of Jewish mysticism Gershom Scholem; and the philosopher Martin Buber. But Schocken had plans to start a major publishing house, which would make classy, compact editions of those and other writers, including Kafka and Walter Benjamin, widely available. Eventually the German and then Palestinian and Israeli firm sprouted an American branch (which published the book you’re now reading), and in time, Schocken bought what would become the daily Hebrew paper of record in Palestine,

Haaretz,

which the family still runs. Apart from that—or not at all apart from that—Schocken was an avid collector of valuable German and Jewish books and manuscripts (he had nearly thirty thousand in his personal library at the time), and it was this latter passion that led him that day from the Stuttgart train station directly to an antiquarian-book dealer, who, without delay, showed him an old and very large poetry manuscript that had recently come onto the market and might be of interest to him. While the dealer didn’t know what the manuscript contained, Schocken—whom Scholem would dub “the mystical merchant”—had, it seems, a sense that the cache was special.

Schocken had long been obsessed with finding a Jewish equivalent for the foundational works of German literature, such as the national epic

The Nibelungenlied

(The Songs of the Nibelung), a poem based on pre-Christian heroic motifs, which eighteenth-century scholars had brought to light. Discovering a work of this magnitude would, Schocken believed, contribute to the strengthening of a precariously vulnerable and insecure

modern Jewish culture, and could refute the common assumption of the day that Jews had no distinctive art form of their own. And so, after looking through the stack of old scraps, which he too could not read, Schocken agreed to the steep selling price of 28,000 marks (roughly $75,000 today) for the mysterious pile of papers.

To appraise his purchase, Schocken called in his A-list of learned friends—among them the novelist Agnon and the de facto Hebrew national poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik—and was informed in short order that his hunch had been right and that he had on his hands a kind of mother lode of Hebrew literature. Prepared by a single anonymous copyist either in Egypt or Turkey in the seventeenth century, the tightly written, two-column manuscript contained some four thousand poems, including the nearly complete works of many of Muslim and Christian Spain’s greatest Hebrew poets (among them Shelomo ibn Gabirol and Moshe ibn Ezra). Some of this work had been lost for centuries. This portable private library of Hebrew Andalusian poetry had passed through various hands, in Iraq, in Bombay, and again in Iraq—where it was rescued by an antiquarian-book dealer and writer from a pile of papers just before being used to heat the next day’s wash water. After all this, it somehow landed in Schocken’s lap in Stuttgart. Ever the practical visionary, Schocken decided to build on this spectacular find by opening a research center that would publish both scholarly studies and critical editions of this manuscript and others like it. On November 4, 1930, Das Forschungsinstitut für hebräische Dichtung—the Institute for the Study of Hebrew Poetry—opened its doors in Berlin. While Schocken 37, as the manuscript came to be known, was

not

from the Geniza, the literary enterprise it gave rise to would go on to play an axial role in the Geniza’s history.