Sacred Trash (19 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

see how afflicted we are within,

and how, without, we’re abhorred—

like Leah, whose suffering you saw,

as you bore witness to her distress.

She was hated at home,

and also despised abroad.

Not each beloved, however, is loved,

and all who are hated are not hated:

some are hated below, but loved on high.

Those You despise are despised,

and those You love are beloved.

We are hated because we love

You who are holy.

I

n dedicating his career, in devoting his days and years to reassembling fragments of elemental poems such as this one—pieces of Judaism’s cosmic puzzle—Zulay, like his colleagues, was propelled by something much deeper than a sense of professional responsibility or even the thrill of the scholarly hunt. Certainly it wasn’t comfort or security, for Schocken paid the frail Zulay very little and—despite his history of heart trouble—drove him hard, demanding that he submit daily reports detailing his research. (Once when the usually reserved researcher complained to the patron about the time and energy the reports were taking, and wasting, he was duly informed: “Mr. Zulay will continue to write the reports and Mr. Schocken will continue not to read them.”) Lingering tensions at the Institute aside, Zulay spoke repeatedly in public—and with particular force in the wake of the Holocaust, which took his sister and her family—of the need for both grunt work and dream work, precision

and

extension, along with the “remnant of a vital faith and naiveté into which every true scholar must tap … Without faith,” he wrote, “there’s no enthusiasm, and without enthusiasm there is no transcendence. The soul withers and one’s vision narrows. Scholarship finds itself mired in trivia and the great goal is forgotten.”

Like Schechter, Zulay knew that even transcendence requires traction—and that meant the continuous work of scholars across generations. Surveying the thousands of disjointed, anonymous manuscript pages—and possibly identifying with what he saw—he likened them to “mute orphans” needing a home that might let them speak. And so, hoping

to make it possible for others to follow where he would one day leave off, Zulay set about the maddening task of cataloging and cross-referencing all the fragments that were arriving daily at the Institute’s broad tables. Maybe he knew that his heart, which had fueled his endless and grueling labor, would soon give way. And it did. Though he worked all day and into the evenings as long and hard as he could, through a flood tide of finds in the forties and beyond, all the while suffering from a debilitating angina that forced him to stop often on his way home from the Institute to lean against walls and regain his strength, he finally succumbed, dying after a fall in his family’s two-room Rehavia apartment one sunny November morning, a few months short of his fifty-fifth birthday.

But as he’d hoped, others did follow—helping to recover what he had called, in his inimitable way, this “lost page from the passport of Hebrew literature.” In a moving, unpublished lecture scribbled on small notepaper and delivered at a Jerusalem rest home where he was convalescing after one of his many hospital stays, Zulay spoke on the fiftieth anniversary of the Geniza’s discovery about how the essence and enduring legacy of the Jewish people cannot be apprehended by the five senses, and won’t be found in conquered lands or constructed cities. Its entirety lies, he said, in what it has written, which can be grasped only by the mind and the spirit. And that literary record, he explains, “is like a tourist’s passport … Each page bears the stamp of a different consulate. And now it happens that one of these pages becomes detached from the passport and is lost.… One day the lost page is found and it turns out that the owner of the passport had once, in the middle of his travels, entered his own country and stayed there for a while, then picked up and gone on his way.” That lost page, Zulay explained to his audience of fellow convalescents, contains the story of the Hebrew poetry of late antiquity written in the Land of Israel.

Since the appearance of Zulay’s 1938 collection of Yannai’s

piyyutim,

more than half of the thirty volumes he envisioned of this verse based on

Cairo Geniza manuscripts have been published in critical editions; and month by month, as they scroll through spools of microfilm and rifle through their files and the indices of their memories, scholars continue to reunite separated pieces of poems. Almost miraculously, it seems, the literary harvest of some seven centuries has been recovered.

But

not quite

miraculously. The late Ezra Fleischer, the principal inheritor of Zulay’s mantle—and someone who would also speak of the electric aspect and sorcery of the

piyyut

’s allusive, self-contained language, as well as of its distant, strange, and “uniquely Jewish beauty”—in a 1999 assessment offered a sobering reminder of just what it is that goes into the work that Zulay and his colleagues did and do. Observing that “the Geniza didn’t change [this] discipline … it built it from the ground up,” he sent forth a paean to the scholar as cultural redeemer.

“The importance of the Geniza’s contribution to the study of Hebrew liturgical poetry,” wrote Fleischer,

cannot be overstated. [But] what has been garnered from this tremendous contribution … is not the contribution of the Geniza itself, and we err in speaking of these finds in the passive formulations [so often employed in this context]. For in this field, as in other fields of research, nothing is given and nothing is discovered. No document is deciphered and no author is identified. No item is dated, no picture reconstructed, and no theory is raised. All these acts are the achievements of a dedicated host of scholars—early and later—great and less great, who devoted their lives to the study of the Geniza and wearied in their labor, sweating blood in their efforts to sort its treasures, sometimes succeeding and sometimes failing, their eyes weakening, their hairlines receding, and their backs and limbs giving out as they grew old and frail—each in his way and at his own pace.

Looking back across the millennia of registration and effacement that the Geniza documents embody, one is tempted to say that

this—

the systole

and diastole of dismissal and deliverance, of composition and copying and translation and erasure, of rejection and retrieval—is the true Isis- or maybe Ezekiel-like mystery at the heart of the enterprise. Risking desiccation for an ultimate vitality, and anonymity for the sake of another’s name, the work of the Geniza’s redeemers, meticulous even in their dreams, brings us back in uncanny fashion to the glory of “the famous” whom the first

payyetan,

Ben Sira, singles out for the highest praise—“those who composed musical psalms, and set forth parables in verse.” In equal measure, however, the efforts of these scholars also recall the fate of the far less conspicuous, a few verses later, “who have no memorial … and perished as though they had not been.” But like Ben Sira’s craftsman, “who labors by night and by day … diligent in his making,” and like his “smith sitting by the anvil, [as] the breath of the fire melts his flesh … his eyes on the pattern of the object, his heart set on finishing his work and completing its decoration,” these deliverers of Hebrew’s makers “maintain the fabric of the world, and the practice of their craft is their prayer.” For in giving themselves day after day to poem after poem and manuscript after manuscript, they become links in the chain of transmission that Schechter himself sought to extend back to the Wisdom of Ben Sira, and from that spirit to its source. And so, in their way, they too partake of eternity.

That Nothing Be Lost

I

t wasn’t always so dramatic.

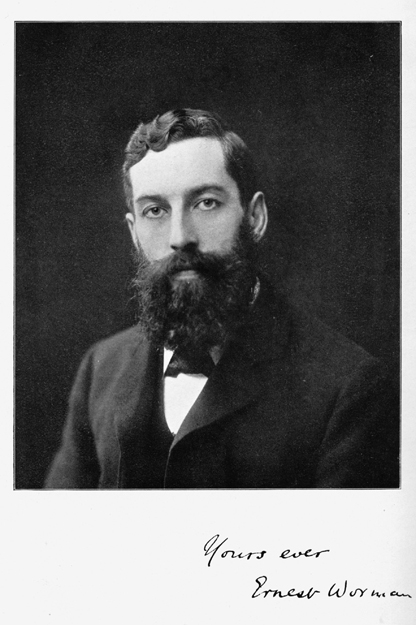

Among the early toilers in what has been called the “salt-mine” of the Geniza, the young Cambridge library assistant—later curator in Oriental literature—Ernest James Worman stands out, in a way, for

not

standing out. Self-reliant, modest, and reserved to the point of opacity, he died at age thirty-eight, and his name is known only (if at all) to those involved at the fine-tooth-comb level of Geniza research. At most, a reference to one of his smattering of scholarly articles will occasionally surface in a footnote to someone else’s scholarly article, though the role Worman played in the preliminary ordering and decipherment of the Geniza cache—and, indeed, in the first, tentative attempts to imagine Jewish life in medieval Fustat—was critical.

Remembered by a school friend as a loner by choice, “strong, reliable, genial and kindly: but not, I think, either enthusiastic or visionary,” Worman was hardly a natural successor to the charismatic Solomon Schechter. “I felt dimly that he would do something excellently,” wrote that same friend of the adolescent Worman. “What that might be I puzzled often, for it did not seem he had—at that time—any conception of it himself.” Yet after Schechter’s 1902 departure for New York, the Geniza collection at Cambridge was left more or less without a guardian. The English Jewish scholar Israel Abrahams had replaced his on-again,

off-again friend Schechter as the university’s Reader in Rabbinics, but was too busy or distracted to pay the Cairo manuscripts much attention. (His lack of interest is peculiar, to say the least, given the fact that Abrahams himself visited Cairo in March of 1898, and wrote letters to his wife declaring it “a real sell” that Schechter was “pretending he had brought away everything” from the Geniza when in fact it seemed there might be just as much remaining in Cairo as what Schechter had taken. The trail of this mysterious pronouncement gives out here—as Abrahams appears not to have brought back more than a few fragments for himself; during his time at Cambridge he basically ignored the Taylor-Schechter collection. He was, it should be said, responsible for the

Jewish Quarterly Review,

the journal he edited with Claude Montefiore, which published almost all the early articles about, and texts from, the Geniza.)

A believing Baptist and former bookshop salesman, the twenty-four-year-old Worman had been hired by the library in 1895, during Schechter’s tenure, and, after being sent by his employers to study Semitic languages as a “non-collegiate” student at the university, he had been recruited to help sort the Cairo fragments. Mathilde Schechter singles him out in her memoir as having provided her husband with the most “actual help” of all those involved in this stage of the work.

Abrahams, for his part, remembered meeting Worman in 1900, when the librarian-in-training knew “little Hebrew and less Arabic.” In the void created by Schechter’s absence, some sense of a calling, though, seems to have stirred within Worman: he realized that

the orphaned and utterly distinctive Geniza collection required care, and, finding no one else prepared to take responsibility, he rose, quietly, to the occasion. “At first,” Abrahams recalled, in a memorial tribute published shortly after Worman’s untimely death of an unspecified illness, “he copied mechanically, but soon revealed an unsuspected and unique power to decipher half-obliterated texts and a remarkable facility in reading doubtful passages.” During this period, he was pressed into service by various far-flung scholars who lacked direct access to the collection. At times he served as a kind of belated (and anonymous) medieval scribe. Without Worman, the soon-to-be-celebrated Lithuanian-born Talmudist Louis Ginzberg, for instance, whom Schechter hired for JTS in 1903, could not possibly have written several of the books that would make him famous in Jewish circles. At one point, Worman copied out in laborious longhand for Ginzberg fifty-five fragments of the Palestinian Talmud, and in another prephotostatic instance he transcribed all the known rabbinic responsa concerning Jewish law in the Cambridge Geniza collection. And it wasn’t just Semitic languages that occupied him. The librarian Francis Jenkinson reckoned that Worman could catalog books in “nearly twenty different languages” and recalled that he once helped another scholar transcribe certain Pali texts, “though he had no previous acquaintance” with that Indic alphabet.

This was drudge work, to be sure, but it seems to have served Worman as an excellent apprenticeship and compelled him to push further. According to Abrahams, “He did not long continue as a mere copyist; he resolved to understand what he transcribed.” And so, “with untiring diligence and almost magical rapidity he made himself master of a difficult language and an intricate literature, his success being rare in the history of the self-taught.” In 1905, after several years spent categorizing, copying, and translating hundreds of fragments onto loose scraps of paper, as he carefully assembled lists of streets, names, buildings, and the like, he published, in the

JQR,

an article that may be the first

attempt to draw from the Geniza’s historical materials a composite view of the Old Cairo community.