Salt (30 page)

Unfortunately for Scotland, Cheshire achieved its new position of power and influence just in time to affect Scotland’s union with England in 1707. After James II, a Catholic, was deposed in England, Presbyterianism was guaranteed for Scotland and the last obstacle to unification was removed. The Scottish and English parliaments merged. But adding Scotland meant bringing Scottish salt into England, and Cheshire merchants had added to the treaty of union numerous stipulations on salt production and pricing aimed at preventing Scottish salt from competing with Cheshire. This was one of several reasons the union had an acrimonious beginning. Almost thirty years before they were joined, John Collins had warned “that unless moderated in its customs” salt competition would breed enmity between England and Scotland.

Meanwhile, Cheshire salt makers would not give up on the idea that the coal beds around them extended to their region. As late as 1899, they drilled a shaft a mile deep. But again, they found only salt.

E

VEN BEFORE TRUE

industrialization had overtaken England, the industrial degradation of the environment was an accepted way of life in Cheshire. Cheshire merchants would look with pride at the sky, blackened twenty-four hours a day from clouds of smoke from the salt pan furnaces, and note the industriousness of their region.

The forests of Cheshire had been chopped down to fuel furnaces. Barren white scars were etched into the pastureland, where the pan scale, the residue that had to be periodically chipped off the salt pans, was dumped. And the earth itself was beginning to collapse.

In 1533, it was reported that the land near Combermere, Cheshire, had fallen in, creating a pit that filled with saltwater. In 1657, another little salt pond appeared at Bickley. In 1713, a hole appeared just south of Winsford in a place called Weaver Hall. All of these funnel-shaped holes were in proximity to salt production, and they all immediately filled with brine. Many locals believed that the holes were the result of abandoned salt mines collapsing. But mining interests pointed out that the sinkholes were not appearing near abandoned shafts. By the last two decades of the eighteenth century, when a new hole sunk every year or two, it started to appear that there was a relationship between the increasing quantities of salt being produced and the collapsing of the earth.

D

ESPITE CHESHIRE’S GROWING

production, England still had that same dangerous dependence on foreign salt that had worried Queen Elizabeth. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was a recurring topic of concern, especially since much of the foreign salt came from England’s principal enemy, France. On land campaigns, each British soldier received a huge ration of salt so that he could acquire fresh meat along his march and salt it to use as needed. The British navy was provisioned with salt and salt foods. Salt was strategic, like gunpowder, which was also made from salt.

In 1746, Thomas Lowndes, a Cheshire native, wrote a book-length report to the admiralty on developing Britain’s own sea salt supply. After studying French and Dutch salt, he, with great excitement, announced that he had discovered the secret of superior salt:

This is the Process

Let a Cheshire Salt-pan (which commonly contains about eight hundred gallons) be filled with Brine, to within about an inch of the top; then make and light the fire; and when the Brine is just lukewarm, put in about an ounce of blood from the butcher’s, or the whites of two eggs: let the pan boil with all possible violence; as the scum rises take it off; when the fresh or watery part is pretty well decreased, throw into the pan the third part of a pint of new ale, or that quantity of bottoms of malt drink: upon the Brine’s beginning to grain, throw into it the quantity of a small nutmeg of fresh butter; and when the liquor has salted for about half an hour, that is, has produced a good deal of salt, draw the pan, in other words, take out the salt. By this time the fire will be greatly abated, and so will the heart of the liquor. Let no more fuel be thrown on the fire; but let the brine gently cool, till one can just bear to put one’s hand into it: keep the brine of that heat as near as possible; and when it has worked for some time, and is beginning to grain, throw in the quantity of a small nutmeg of fresh butter, and about two minutes after that, scatter threw the pan, as equally as may be, an ounce and three quarters of clean common allom pulverized very fine; and then instantly, with the common iron-scrape-pan, stir the brine very briskly in every part of the pan, for about a minute: then let the pan settle, and constantly feed the fire, so that the brine may never be quite scalding hot, nor near so cold as lukewarm: let the pan stand working thus, for about three days and nights, and then draw it.

The brine remaining will by this time be so cold, that it will not work at all; therefore fresh coals must be thrown upon the fire, and the brine must boil for about half an hour, but not near so violently as before the first drawing: then, with the usual instrument, take out such salt as is beginning to fall, (as they term it) and out it apart; now let the pan settle and cool. When the brine becomes no hotter than one can just bear to put one’s hand into it, proceed in all respects as before; only let the quantity of allom not exceed an ounce and a quarter. And in about eight and forty hours after draw the pan.—

Thomas Lowndes,

Brine-salt Improved, or The Method of Making Salt from Brine, That Shall Be as Good or Better Than French Bay-salt,

1746

Lowndes assured the admiralty, “The greater the quantity is of salt made my way, the more satisfied the public will be, that my secret is truly made known.” But, understandably, some found his secret to be excessive for just making salt, a product whose commercial success depended on low production costs. Two years later, the physician William Brownrigg in a widely distributed work,

The Art of Making Common Salt,

criticized Lowndes’ formula, writing that “a purer and stronger salt can be made, and at less expense.”

Cheshire salt needed to be not only better but, even more important, cheaper. Almost seventy-five years earlier, Dr. Thomas Rastel of Droitwich had written that Droitwich had simplified salt making, eliminating the cost of blood used in Cheshire brine by making an egg white scum, a technique still used in cooking to remove impurities in meat stocks for a clear aspic:

For clarifying we use nothing but the whites of eggs, of which we take a quarter of a white and put it into a gallon or two of brine, which being beaten with the hand, lathers as if it were soap, a small quantity of which froth put into each vat raises all scum, the white of one egg clarifying 20 bushels of salt, by which means our salt is as white as anything can be: neither has it any ill savour, as that salt has that is clarified with blood. For granulating it we use nothing for the brine is so strong itself, that unless it be often stirred, it will make salt as large grained as bay-salt.—

Dr. Thomas Rastel, 1678

The goal was always to make bay salt, salt that resembled the sea salt of Bourgneuf Bay, because this was the salt of the fisheries. Lowndes mentioned in his treatise that he had received a letter from a Captain Masters, dated June 5, 1745, estimating that the Newfoundland cod fishery used “at least ten thousand tons” of salt annually.

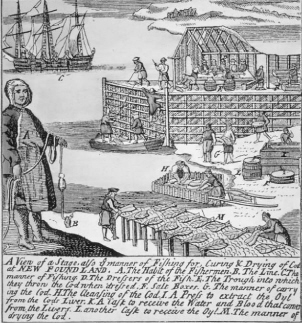

An eighteenth-century English engraving of codfish being salted and dried in Newfoundland.

The Granger Collection

Between 1713 and 1759, through nearly global warfare with France, England had acquired most of the codfish grounds of North America. The English were excited about their new cod potential. But even a decade before they had achieved their greatest victories, Brownrigg had warned that in order to take advantage of the acquisition of Cape Breton alone, the French end of Nova Scotia, England would have to increase its supply of salt.

North American cod seemed limitless, and the only impediments to British profits were the number of ships and fishermen, and the supply of salt.

S

TUDYING A ROAD

map of almost anywhere in North America, noting the whimsical nongeometric pattern of the secondary roads, the local roads, the map reader could reasonably assume that the towns were placed and interconnected haphazardly without any scheme or design. That is because the roads are simply widened footpaths and trails, and these trails were originally cut by animals looking for salt.

Animals get the salt they need by finding brine springs, brackish water, rock salt, any natural salt available for licking. The licks, found throughout the continent, were often a flat area of several acres of barren, whitish brown or whitish gray earth. Deep holes, almost caves, were formed by the constant licking. The lick at the end of the road, because it had a salt supply, was a suitable place for a settlement. Villages were built at the licks. A salt lick near Lake Erie had a wide road made by buffalo, and the town started there was named Buffalo, New York.

When Europeans arrived, they found a great deal of salt making in North American villages. In 1541, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, traveling up the Mississippi, noted: “The salt is made along a river, which, when the water goes down, leaves it upon the sand. As they cannot gather the salt without a large mixture of sand, it is thrown into certain baskets they have made for the purpose, made large at the mouth and small at the bottom. These are set in the air on a ridge pole; and water being thrown on, vessels are placed under them wherein it may fall, then being strained on the fire it is boiled away, leaving salt at the bottom.”

Hunter groups that did not farm did not make salt. An exception was the Bering Strait Eskimo, who took reindeer, mountain sheep, bear, seal, walrus, and other game and boiled it in seawater to give a salty taste. Many, such as the Penobscot, Menomini, and Chippewa, never used salt before Europeans arrived. Jesuit missionaries in Huron country complained that there was no salt, though one missionary suggested that Hurons had better eyesight than the French and attributed this to abstinence from wine, salt, and “other things capable of drying up the humors of the eye and impairing its tone.”

Other books

The Officer and the Proper Lady by Louise Allen

April Holthaus - The MacKinnon Clan 02 by Escape To The Highlands

Maid of Murder by Amanda Flower

Virus by Ifedayo Akintomide

Vampire in Paradise by Sandra Hill

The Night Counter by Alia Yunis

The Guns of Tortuga by Brad Strickland, Thomas E. Fuller

Love Walked In by de los Santos, Marisa

Captivate Me (Book One: The Captivated Series) by S.J. Pierce

A Lonely Magic by Sarah Wynde