Salt (32 page)

T

HE BRITISH FIRST

arrived in North America in the north, at Newfoundland, and they took cod. They next arrived in the south, the Caribbean, where they took salt, which they needed for the cod. Only after they had a significant population of colonists in between did they think of America as a market in which to sell Liverpool salt.

To the British admiralty, the solution to a lack of sea salt was to acquire through war or diplomacy places that could produce it. Portugal had both sea salt and an important fishing fleet, but needed protection, especially from the French who were regularly seizing their fishing boats. And so England and Portugal formed an alliance trading naval protection for sea salt.

The Portuguese alliance gained England access to the Cape Verde Islands, where British ships could fill their holds with sea salt on their way across the Atlantic. The islands on the eastern side of the archipelago, Maio, Boa Vista, and Sal, which means “salt,” had marshes with strong brine, and in the seventeenth century Portugal granted the British exclusive use of the salt marshes of Maio and Boa Vista.

British ships had only from November until July to make salt before the summer rains ruined the brine. They usually stopped off in January, anchoring off Maio, which they called May Island. From there the sailors would row their launches less than 200 yards to a broad beach. Behind the beach was a salt marsh, where a mile-long stretch of ponds would be eight inches deep in brine. It could take months before the sailors had scraped enough salt crystals for the ship to be full. Sometimes early rains would force them to leave. Some ships had to go to Boa Vista because they found too many crews already working at Maio. At Boa Vista the brine was weaker and took longer to crystalize and the anchorage was farther out, forcing the sailors to row a mile to bring salt to the ship.

But sea salt was valuable enough for a shipload of it to be worth the labor of an entire ship and crew for several months.

I

N THE SEVENTEENTH

and eighteenth centuries, while European powers were fighting bitterly for Caribbean islands on which to grow sugarcane, northern Europeans—the English, the Dutch, the Swedish, and the Danes—also looked for islands with inland salt marshes like the Cape Verde Islands.

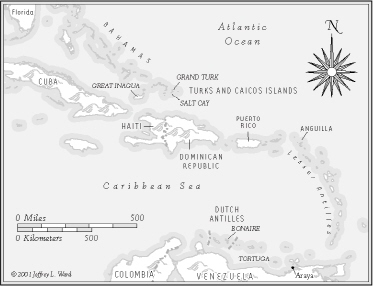

In 1568, under William of Orange, the Dutch began an eighty-year independence struggle against Spain, which cut them off from Spanish salt. But in the Americas, the Dutch could come ashore unobserved on the coast of Venezuela at Araya, a hot and desolate eighty-mile lagoon, and steal Spanish salt from the beach, where Caribbean seawater evaporated into a thick white crust. The Dutch also got salt from Bonaire in the nearby Dutch Antilles.

The British gathered salt illegally from the Spanish on another small island in the area called Tortuga or Salt Tortuga, which is today part of Venezuela. They also made salt on Anguilla and the Turks Islands, which had the advantage of being closer to North America, where the cod fishery was. They would stop off in one of the salt islands, and, as in the Cape Verdes, the sailors themselves would scrape up salt and load up their ships and sail on to New England, Nova Scotia, or Newfoundland.

Fearing enemy warships and pirates, the salt ships traveled in convoys. They also did this in Europe for the same reasons. Huge armed fleets of ships of various nationalities would anchor off Le Croisic while salt was being loaded. Sailors were not allowed to be armed when they came ashore, because if convoys of two nations arrived at the same time, a port scuffle could turn into a land war. English and Dutch sailors were especially hostile toward each other.

At the end of winter, fleets of several dozen British ships, accompanied by warships, would meet in Barbados. There they would combine into one large fleet and choose a commander. Then they would go to one of the salt islands, usually Tortuga, and the crews would work for months to load their ships. If the fleet was too large or if it was a wet year, there would not be enough salt to fill all the ships, and since they were only together as a temporary arrangement, they would compete, working as fast as possible, each ship trying to secure a full hold. Then they would sail north together, and when they believed they were out of danger, especially from the Spanish fleet, each would veer off on its own course.

I

N 1684, WHEN

Bermuda, first explored by the British more than 150 years earlier, finally became a British colony, the first governor was given instructions to “proceed to rake salt.” English ships sailing to American colonies could stop off in this cluster of minuscule islands in the middle of the Atlantic some 600 miles from the coast of North America, and pick up salt for the fisheries. It was a chance to make Bermuda productive.

But the climate in Bermuda was not warm and sunny enough for a successful sea salt operation. What Bermuda did have was cedar. So Bermudians, most of whom were originally sailors from Devon, built small, fast sloops out of cedar. Until the early eighteenth century, when New England fishermen invented the schooner, the Bermuda sloop with its single mast and enormous spread of sails was considered the fastest and best vessel under sail, capable of outrunning any naval ship. These sloops dominated the trade between the Caribbean and North American colonies and were even used in the Liverpool-to-West Africa trade.

In the Caribbean, the leading cargo carried to North America—more tonnage than even sugar, molasses, or rum—was salt. The leading return cargo from North America to the Caribbean was salt cod, used to feed slaves on sugar plantations.

In the southern part of the Bahamas chain and the group south of it known as the Turks and Caicos, salt rakers found small islands with brackish lakes in the interior. Great Inagua, Turk, South Caicos, and Salt Cay (pronounced

KEY

) had salty inland lakes well suited for salt making. Since Columbus and his Spanish successors had already annihilated the indigenous population, these scarcely inhabited islands were easily converted into salt centers.

Great Inagua was first raked by the Spanish and Dutch. After the Spanish killed the few local tribesmen, it was an uninhabited island and sailors from various nations stopped by and filled their ships. The Spanish named it Enagua, meaning “in water.” In 1803, salt rakers from Bermuda built a small town, Matthew Town, by the edge of a salt pond at one end of the flat grassy island.

First came salt rakers, who simply scraped up what had evaporated on the edge of ponds. The crew would be dropped off on the island, where they would spend a few months or sometimes as long as a year gathering salt while the captain and three or four slaves would sail off, fishing for sea turtle, scavenging shipwrecks, and trading with pirates or between islands. Sometimes they would hide in coves by treacherous rocks or uncharted shoals and wait, or even lure the ships onto the rocks so that they could scavenge them.

An eighteenth-century Bermuda governor complained that “the Caicos trade did not fail to make its devotees somewhat ferocious, for the opportunities were in picking, plundering and wrecking.” He was also concerned with the practice of sending the slaves plundering while the free sailors were gathering salt. The governor wrote, “The Negroes learned to be public as well as private thieves.”

When the captain and his slaves had finished with their profitable adventures months later, they would return and pick up their crew and a full hold of salt to sell in the North American colonies.

In the 1650s, British colonists from Bermuda sailed down to Grand Turk, a small desert island, and Salt Cay, its tiny neighbor, only two miles long by one and a half miles wide. In Salt Cay, passing ships would stop to rake the ponds that occupied one third of the island. In the 1660s, Bermudians began exploiting it more systematically, at first only in the summers, which were dry.

By 1673, the arrival of Bermudian rakers on Salt Cay was a regular event. Five years later, salt raking had become equally well organized on the slightly larger island to the north, Turk or Grand Turk Island, which was named after a native cactus thought to resemble a Turkish turban. But the Spanish would come in the winter and take the salt rakers’ tools and destroy their sheds. By the early 1700s, Bermudians started living full-time on Salt Cay to protect their property. No one knows when the small harbor was built with its stone piers, but it was the most stormproof in the Turks and Caicos, a safe shelter for ships to spend a few weeks loading. But as vessels became larger, the little harbor was too shallow, and light ships had to be used to carry the salt out to mother ships anchored offshore.

Salt Cay salt makers built a system of ponds and sluices. Every year, they had to spend weeks overhauling the system. The ponds had to be drained in order to mend the stone or clay bottoms so that they would hold water and not crumble into the salt. Then the ponds would be refilled for the slow process of solar evaporation.

Salt makers came from Bermuda and built large stone houses in the Bermudan style with thick walls to hold up a cut stone roof built in steps like a pyramid. The heavy roof was designed to resist hurricanes. Mahogany furniture was brought to the island. These were the manor houses of slave plantations, but they had none of the elegance of the Virginia tobacco, or Alabama cotton, or West Indian sugar planters’ homes.

The salt makers’ house had an eastern porch that looked out over his salt ponds and a western porch that looked over his loading docks. The houses were always built at the water’s edge by a loading dock. The salt, too valuable to entrust to anyone else, was kept in the basement, which was one story below ground, but the windowless first story of the house had no floor, so that actually each house had a two-story storage bin at its base. Salt was the salt makers’ wealth, and they watched over it day and night.

Other books

Her Accidental Boyfriend: A Secret Wishes Novel (Entangled Bliss) by Bielman, Robin

Assassin Mine by Cynthia Sax

My Sweet Valentine by Dairenna VonRavenstone

Redeeming Kyle: 69 Bottles #3 by Zoey Derrick

Brie's Christmas Pearls (Submissive in Love, #3) by Red Phoenix

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead by James Hadley Chase

Nobody Is Ever Missing by Catherine Lacey

Just A Little Taste by Selena Blake

Ethics of a Thief by Hinrichsen, Mary Gale

Making War to Keep Peace by Jeane J. Kirkpatrick