Salt (53 page)

They walked slowly along the dusty road, twelve miles a day, with the horizon rippling with heat. Marching in the lead, with a bamboo walking stick, was the bony, sixty-year-old Gandhi, his slow steps full of self-assurance and determination. Some grew too tired or their feet became too sore, and they retreated to carts. A horse was kept nearby for Gandhi, but he never used it.

The march began each day at 6:30

A.M.

By then, Gandhi had been up for hours, spinning cloth, writing articles or speeches. He was seen writing letters by moonlight in the middle of the night. He stopped to speak to the villagers who gathered eagerly to see the mahatma, and he invited them to join him and to break the British salt monopoly. He also preached better sanitation and urged them to abstain from drugs and alcohol, to treat the untouchables as brothers, and to wear khaddar, the homespun cloth of India, rather than imported British textiles. In the 1760s, before the American Revolution, John Adams also had urged Americans to wear homespun instead of British imports.

“For me there is no turning back whether I am alone or joined by thousands,” Gandhi wrote. But he was not alone. Along the way, local officials showed support by resigning their government posts. The Anglo-Indian press ridiculed him; The

Statesman

of Calcutta said that he could go on boiling seawater indefinitely till Dominion status was achieved. But the foreign news media was fascinated by this little man marching against the entire British Empire, and people all over the world cheered his improbable defiance.

The press reported on his power to persuade, his determination. But the viceroy, Lord Irwin, who was being informed by British agents, was convinced that Gandhi would soon collapse. He even wrote the secretary of state for India that Gandhi’s health was poor and that if he continued his daily march, he would die and “it will be a very happy solution.”

On April 5, after twenty-five days of marching, Gandhi reached the sea at Dandi, not with his seventy-eight followers behind him but with thousands. Among them were elite intellectuals and the desperately poor and many women, including affluent women from the cities.

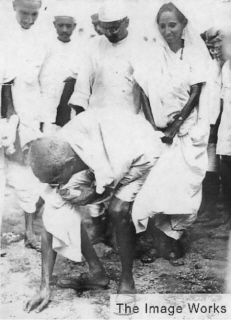

Through the night Gandhi led his followers in prayer by the warm, lapping waves of the Arabian Sea. At first light, he led a few into the water for a ceremony of purification. Then he waded out and felt his way up the beach with his spindly legs to a point where a thick crust of salt, evaporated by the sun, was cracking. He bent down and picked up a chunk of the crust and in so doing broke the British salt law.

“Hail, deliverer!” a pilgrim shouted.

O

N THE OTHER

side of India, the people of Orissa decided to begin salt making even before Gandhi arrived in Dandi, and they resolved to continue whether the rest of the country followed Gandhi’s example or not. They opened a camp at Cuttack, to which volunteers from different parts of Orissa came and signed oaths vowing to dedicate themselves to resisting the salt laws. Regular meetings were held to discuss the nature and importance of the salt satyagraha. The British banned such meetings, and people giving public addresses on the subject were arrested and imprisoned.

On April 6, 1930 at 8:30

A.M.

Gandhi publicly violated British salt law by picking up a piece of salt crust in Dandi on the coast of the Gujarat peninsula.

The Image Works

A public salt making was organized in Orissa on April 6 to coincide with Gandhi’s. Locals blew conch shells and tossed flower petals to announce their day of nonviolent civil disobedience. As they traveled along the coast, their leader, Gopabandhu Choudhury, was arrested, but the group continued. On April 13, at 8:30

A.M.

, they reached their destination, Inchuri, where thousands turned out to watch them break the law.

They leaned over and scooped up handfuls of salt. The police tried to forcibly remove the salt from their hands. A crowd of dissidents ran onto the beach, picked up salt, and were taken away by the police. The protests went on for days, with waves of salt makers followed by waves of police followed by more salt makers. The police called in reinforcements. Soon the jails were filled, and more and more police and protesters were rushing into Inchuri. The police staged charges, harmless but designed to scare. It didn’t work.

The salt protests spread along the coastline. A large number of the dissidents were women. Some of the salt-making demonstrations were even organized by women. The police used clubs, but the protesters remained nonviolent. After the demonstrations were over, 20,000 people turned out to throw flowers and cheer the released satyagrahis returning home from prison.

It took only a week for Gandhi’s ceremonious moment on Dandi beach to become a national movement. Salt making, really salt gathering, was widespread. In keeping with Gandhi’s other teachings, protesters were picketing liquor stores and burning foreign cloth. Salt was openly sold on the streets, and the police responded with violent roundups. In Karachi, the police shot and killed two young Congress activists. In Bombay, hundreds were tied with rope and dragged off to prison after the police discovered that salt was being made on the roof of the Congress headquarters.

Teachers, students, peasants—it seemed most of India was making salt. Western newspapers covered the campaign, and the world seemed to sympathize, not with the British but with the salt campaigners. White “Gandhi hats” became fashionable in America, while the mahatma remained bareheaded.

But the protest movement had spread to other groups that did not use the force of truth. One such group raided an East Bengal arsenal and killed six guards. When armored cars were sent against demonstrators in Peshawar, in the northwest, one armored car was attacked and set on fire. A second car opened fire with machine guns and killed seventy people.

Gandhi sent a letter to Lord Irwin protesting police violence, which began, as always, “Dear Friend.” He then announced that he was going to march to the government-owned saltworks and take them over in the name of the people. British troops went to the village near Dandi, where the leader was sleeping under a tree, and arrested him.

The

Manchester Guardian

warned the British government that the arrest of Gandhi was a costly misstep further provoking India. The

Herald

, the official organ of the Labour Party, also opposed the arrest of Gandhi.

While India exploded, Gandhi sat in prison spinning cotton. As many as 100,000 protesters, including all of the major leaders and most of the minor local ones, were in prison. Congress committees were declared illegal. Still, the salt movement went on. The government tried to negotiate with the jailed leaders. Disapprovingly, Winston Churchill said, “The Government of India had imprisoned Gandhi and they had been sitting outside his cell door, begging him to help them out of their difficulties.”

On March 5, 1931, Lord Irwin signed the Gandhi-Irwin pact, ending the salt campaign. Indians living on the coast were to be permitted to collect salt for their own use only. Political prisoners were released. A round table conference was scheduled in London to discuss British administration in India. And all civil disobedience was to be stopped. It was considered a compromise. To some, the British had won on most points, but Gandhi was pleased because he thought that for the first time England and India were talking as equal partners rather than master and subject.

Irwin suggested they drink a tea to seal the pact, and Gandhi said his tea would be water, lemon, and a pinch of salt.

Gandhi had emerged as the leading voice of Indian aspirations, and the Indian National Congress had become the primary organization of the independence movement. In 1947, India became independent, and five months later Gandhi was assassinated by a fellow Hindu who mistakenly interpreted his efforts to make peace with Muslims as part of a plan to favor them. Jawaharlal Nehru, the son of a patrician lawyer who helped found the Indian National Congress, became prime minister. Nehru was once asked how he remembered Gandhi, and he said he always thought of him as the figure with a walking stick leading the crowd onto the beach at Dandi.

I

N 300 B.C.,

long before the British arrived, a book titled

Arthasastra

recorded that under India’s first great empire, founded by Chandragupta Maurya, salt manufacture was supervised by a state official called a

lavanadhyaksa

under a system of licenses granted for fixed fees. More than a half century after the British left, salt production was still supervised by the government.

After 1947, independent India was committed to making salt available at an affordable price. Salt production in independent India was organized into small cooperatives, most of which failed. The industry is now controlled by a few powerful salt traders. The government is supposed to look after the interests of the salt workers through the Salt Commissionerate. Across the river from Gandhi’s ashram, in Ahmadabad, Gujarat’s Salt Commissionerate stands accused by many workers of looking after the traders rather than the workers.

The rock salt of Punjab is now in Pakistan. The west coast, Gujarat and the Rann of Kutch, has become India’s major salt producer, whereas Orissa, with only six saltworks surviving into contemporary times, is no longer an important salt-producing region. Almost three-quarters of India’s salt is now produced in Gujarat. Gujaratis, with their coastal economy, are not among India’s poorest population. But the wages in the saltworks are so low that most salt workers come from more impoverished regions. Every year, in September, thousands of migrant workers arrive in Gujarat to work seven-day weeks until the salt season ends in the spring. They often earn little more than a dollar a day. Hundreds of workers are undeclared so that the salt traders can avoid paying them social benefits and circumvent laws forbidding child labor. Many of the workers are from the lowest caste and are hopelessly in debt to the salt producers. The glare of the salt in the dry-season sunlight renders many of the salt workers permanently color-blind. And they complain that when they die, their bodies cannot be properly cremated because they are impregnated with salt.

A storm that hit Gujarat in June 1998 decimated this cheap labor force, killing between 1,000 and 14,000 people, depending on whose count is believed. The price of Indian salt soared. But by the end of the year, the workforce had been replaced and the price had dropped back. Once again, salt could be purchased at a low, affordable price—which every Indian citizen has a right to expect.

Other books

The Pure in Heart by Susan Hill

Dead and Everything (Eve Benson: Vampire Book 2) by P. S. Power

Blood Lust by T. Lynne Tolles

PICTURES OF YOU: a gripping psychological suspense thriller by Diane M Dickson

BREAK ME FREE by Jordan, Summer

Kinflicks by Lisa Alther

Touching Smoke by Phoenix, Airicka

Stonehenge a New Understanding by Mike Parker Pearson

Ryker by Schwehm, Joanne

His Private Nurse by Arlene James