Salt (55 page)

I

N THE EARLY

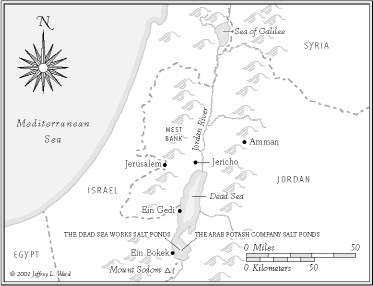

twentieth century, Theodor Herzl, an Austrian visionary, began writing of the return of Jews to their homeland. In contemplating the viability of a Jewish state, he hypothesized that one of its valuable resources would be the Dead Sea, from which the new state could extract mineral wealth, including bromine and potash. In the 1920s, Moishe Novamentsky, a Jewish engineer from Siberia, established the Palestine Potash Company along the northern coast of the Dead Sea, in British-ruled Palestine.

In 1948, when the Arab League attacked the newly formed state of Israel, the Jordanian army crossed the Jordan River and seized most of the Dead Sea area, including the Palestine Potash Company, much of the Judean desert, and the eastern side of Jerusalem. For the next nineteen years, gun- and rocket fire crossed the border. The Potash Company was moved to Israeli-held land in the southern Dead Sea area and renamed the Dead Sea Works. The workers of the Dead Sea Works became the first Israeli pioneers in this frontier wilderness, living in rough huts with little electricity, limited water, and no air-conditioning. There too they were regularly shelled by Palestinians on the Jordanian side. Cut off from Jerusalem and much of Israel by the Jordanians, the Dead Sea Works found its own water wells. Today the saltworks have relocated along extensive artificial ponds, and the original camp—the small houses and dining hall abandoned on a dusty plateau—is being restored as a monument to the resourceful adventurers who built Israel.

In 1956, some Israeli soldiers, having finished a tour of duty at the Dead Sea, decided to stay, drawn to a freshwater spring called Ein Gedi where a green wadi leads to a tall, thin cascade magically tumbling water out of the desert, one of only two waterfalls in Israel that flow all year. Pliny had mentioned the spot for its remarkable fertility, though, he said, it had been destroyed in war with the Romans. Possessed by Herzl’s Zionist dream of making the desert bloom, the Israeli soldiers founded a collective settlement in Ein Gedi, a kibbutz, where everyone worked for the profit of the community, children were raised collectively in separate dormitories, and a paradise was to bloom on the Judean frontier. Plants were brought into a garden with lawns and tropical trees from Asia and Africa—lichees, brilliant red flamboyants, thick, climbing, green broad-leafed vines. Birds, spotting the rich green garden from the air, have made it a principal stop on their Europe-Africa migration.

It had all been predicted in Herzl’s 1902 novel,

Old New Land

, in which he imagines visiting the new Jewish state in 1923 and finding the Jews not only exploiting the Dead Sea’s mineral wealth but making the desert green through irrigation and living in farm collectives that exported produce to Europe. However, he also predicted that Israel would be a German-speaking nation and that Arabs would eagerly welcome Jews for the economic development they would bring to the region.

The kibbutz grew, building a health spa on the shore of the Dead Sea that offered Dead Sea mud and Dead Sea water, both of which had long been supposed to have healing properties. By the late 1960s, the kibbutz had built a hotel that today is one of Israel’s leading tourist attractions.

In 1960, the Israelis built a hotel along another spring to the south, Ein Bokek. Since the Jordanians were to the north of Ein Gedi, the south was the only place for Israelis to develop. The Dead Sea Works had brought in water and electricity, and now the visitor could be offered the miracle that makes deserts livable: air-conditioning. But the Ein Bokek development was not really on the Dead Sea. Just south of the sea, the salt company had pumped Dead Sea water into a flooded area divided by dikes. There, the brine was moved from pond to pond, ever more concentrated until finally the precious salt minerals fell out of the solution in the form of a white slush that was scooped up. Still, these artificial salt ponds, concentrated to a brilliant turquoise, made a stunning sea, and sand was brought in for small beaches.

By 2000, Ein Bokek had 4,000 rooms in fourteen hotels, all with Dead Sea health spas offering a variety of treatments—an improbable oasis of white and pastel high-rises on the shores of a saltworks. The Israelis keep building ever taller hotels, and the discreet screens used by religious people to separate women’s and men’s nude sunbathing on the roofs of older hotels are of little help when hundreds of guests can look down from newer hotels ten stories above.

The Israeli Defense Ministry pays for every wounded Israeli veteran, and there are many, to visit a Dead Sea spa hotel two times a year. Both Danish and German government health insurance will pay for a stay in an Ein Bokek spa hotel. The Israeli tourism business has in recent years begun rethinking its markets. It has not attracted Jews in the numbers hoped for. Herzl had said that attracting the Jewish diaspora would be a slow process, but after a half century as a nation, according to the Israeli Ministry of Tourism, only 17 percent of American Jews have ever visited Israel. Christian American tourism does better, and Germans, either seeking sunshine or health spas, are the new booming trade, Israelis report without the least note of irony. Germans are the largest national group, after Israelis, to visit Ein Bokek. They also comprise one third of the visitors to Ein Gedi.

B

UT THERE IS

a problem.

In 1985, the Ein Gedi kibbutz built a new spa on the edge of the Dead Sea. It has the atmosphere of a public beach, packed on Saturdays with Israelis lined up like crudely formed clay statues, bizarrely coated in thick black mud, baking to a gray crust in the sun. But though the spa was originally built on the water’s edge, today a trolley carries bathers to the water almost a mile away. The sea recedes from Ein Gedi about fifty yards a year.

In the first century

A.D.

, Pliny described the now 45-by-11 mile body as being 100 miles by 75 miles. A two-lane road that used to run along the sea is now several miles inland. A flat, rocky plain that was once the sea’s floor leads to the water’s edge. Mountains rise up against the other side of the road, and on one rock about ten feet above the pavement the initials

PEF

are written. This is where the Palestinian Exploration Fund, a British geographic organization, marked the surface of the Dead Sea in 1917.

The greatest problem of the Dead Sea is that since the Israelis built the National Water Canal from the Sea of Galilee, the Galilee has served as Israel’s primary source of freshwater, greatly reducing the flow to the Jordan River, which in turn is siphoned off by Jordanian farmers in the valley, who provide 90 percent of Jordan’s produce. Not much water is left for the dying ancient sea.

Pliny called the Jordan “a pleasant stream” and said, “It progresses, seemingly with reluctance, toward the gloomy Dead Sea by which it is finally swallowed.” But today the stream that approaches the Dead Sea is a little rush of silted water in a reedy gully a few feet wide. Lieutenant Lynch’s specially designed boats or even a one-man rowboat could not navigate this river to the Dead Sea.

Is the Dead Sea becoming a Saharan-like sebkha, a dried bed ready for scraping? Currently, the sea loses about three feet in depth every year. Since the northern end is in places 1,200 feet deep, it is thought that the sea has several centuries left. Another theory is that it will shrink but reach a level of such concentration that it will no longer evaporate, which seems optimistic considering the ubiquitous dry salt beds in all of the world’s major deserts.

A few years ago, “Dead-Med” became a popular phrase in Israel. The plan was to dig a waterway reconnecting the Dead Sea with the Mediterranean. This idea currently appears deader than the Dead Sea. The introduction of Mediterranean water would alter the composition of the Dead Sea, and mineral extraction would no longer be practical, thereby destroying one of Israel’s most profitable industries.

The Dead Sea has its health spas and tourism, but the biggest business in the area, as Herzl had predicted, is the Dead Sea Works, which has even become an international company, investing in a potash mine in Spanish Catalonia, near Cardona.

The Jordanians, apparently having read their Herzl, are also counting on their Dead Sea works. The Arab Potash Company is a mirror image directly across from the Israeli company. This is the Arab-Israeli border: two sets of earthen dikes less than three feet high with a cloudy turquoise Israeli evaporation pond on one side and a cloudy turquoise Jordanian pond on the other, and in between about 100 yards of white and rust and amber soil where minerals from the two ponds leach through the earthworks.

Until a peace treaty was signed with Israel in 1996, the Jordanian Dead Sea region was a military zone, off limits to civilians. Now, at peace, Jordan has few resources but is full of plans. Mohammed Noufal observed with a smile, “All we need is Israel’s technology, Egypt’s workers, Turkey’s water, and Saudi Arabia’s oil, and I am sure we can build a paradise here.”

The Jordanians too are building health spas and attracting German tourists of their own. But for them also, salt will remain the leading economic activity. There are four Israeli pumps and two Jordanian pumps moving Dead Sea water into evaporation ponds.

Sodium chloride, the salt of the past, is the first to precipitate out of concentrated brine. But hauling in bulk out of the Judean desert is too costly because of the lack of a waterway connection. The climb through the mountains is too steep for a railroad. The salt had to be hauled by truck until the Israelis built an eleven-mile-long conveyer belt. It carries 600 to 800 tons of salt in seventy minutes to the town of Tzefa, where the land is then level enough for a railroad to the Mediterranean.

This system is still too expensive for sodium chloride to be profitable. But the Israeli company sells 10 percent of the potassium chloride—potash—in the world, a product much in demand for fertilizers. It also produces liquid chloride and bromide for textiles and pharmaceuticals and methyl bromide, a pesticide. Under pressure because of damage to the ozone layer, it is phasing out methyl bromide production. The Jordanians say they are thinking of starting it up.

The Dead Sea Works believes its future is in magnesium. Magnesium chloride, what Lieutenant W. F. Lynch called “a nauseous compound,” is the salt that gives the sea its bitter unpleasant taste. It is a slightly more expensive but less corrosive alternative to sodium chloride for deicing roads. From magnesium chloride, the Dead Sea Works also produces magnesium, a metal that is seven times stronger than steel and lighter than aluminum. The company has invested in a joint venture with Volkswagen to make car parts. Will one more Herzl prediction come true and Israel become German-speaking after all?

Once the sodium chloride precipitates out, falling to the bottom of the pond, the principal target mineral is 6H2O MgCl2 KCl. This grayish crystal sludge, called carnolite, fuses potassium chloride, sodium chloride, and magnesium chloride into a single crystal.

The sodium chloride that precipitates out before carnolite is allowed to fall to the bottom of the pond, constantly raising the height of the pond bottoms. The company keeps building the dikes higher, but the raised ponds have been flooding hotel basements, to the great irritation of the tourism industry. The Dead Sea Works counters that its workers were the pioneers who dug the wells and provided the water and electricity that made the area usable in the first place. Tensions persist. This is, after all, the Middle East. The Dead Sea Works, recognizing the problem, has started a flood prevention program to help hotels.

Common salt has become a nuisance.

Other books

Fortunes & Failures - 03 by T. W. Brown

PowerofLearning by Viola Grace

DeeperThanInk by M.A. Ellis

Novel 1963 - Fallon (v5.0) by Louis L'Amour

Murder in Focus by Medora Sale

Matchpoint by Elise Sax

The Trouble With Pixies (Edinburgh Elementals Book 1) by Gayle Ramage

Hand in Glove by Robert Goddard

Halloween IV: The Ultimate Edition by Nicholas

Soul Eater by Michelle Paver