Salt (65 page)

The sea is a blue-green that is almost blinding in its brightness. The streets are paved and empty except for dogs and chickens. The occasional traffic is almost always a pickup truck that says “Morton Salt” on the side. Matthew Town, the capital and only real town, is a grid of about a dozen intersecting streets with little green-trimmed, or yellow, or sometimes hot-pink houses interspersed with overgrown empty lots. Twelve hundred people live in this town and a few hundred on the rest of the island. The general store, well stocked with frozen foods, the leading hotel—a two-story house with a turquoise-green picket fence—the drinking water, the electricity, and most everything else on the island comes from Morton Salt. Morton has 200 employees at the salt-works, but many more in Matthew Town.

Great Inagua is a flat limestone-and-coral island. The soil is impregnated with salt from the sea, which leaches into the inland ponds. In addition, the island is favorable for making sea salt because it is sheltered by the large Caribbean islands of Hispaniola, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, and so rarely is hit full force by a hurricane.

The leaching soil turns the water in an inland lake saltier than seawater. Seawater is pumped into reservoirs in the inland lake, where it remains, sheltered from tides, for nine months, concentrating from solar evaporation, while attracting more salt from the soil. Then it is pumped to a crystalizing pond for twelve more months until it is reduced to a three-inch layer of salt crystals.

In the wetlands surrounding the inland lake live 50,000 to 60,000 flamingos, feeding off the brine shrimp in the 38,000 acres of evaporation ponds. Believing that the shrimp aid evaporation, Morton buys additional brine shrimp eggs from the ponds in San Francisco Bay.

Morton produces no table salt in Great Inagua, only crude road deicing salt, an industrial grade for water softeners, a quality product for the chemical industry, and a fishery salt that is bought by cod fishermen in Iceland. Almost none of Great Inagua’s salt stays in the Bahamas. Bahamians buy their water softeners, often made from Great Inagua salt, from Florida. For Morton, Great Inagua has the sea salt production closest to the United States’ east coast and produces 1 million tons of salt per year. “You have to drive production,” said Geron Turnquest, vice president of operations at the Great Inagua Morton saltworks. “It is volume that makes the profit here.”

M

OST

S

ALTWORKS IN

the Caribbean either have been taken over by large international companies or have been abandoned. In the nineteenth century, the Turks Island Company was an important international company. It even owned a saltworks on San Francisco Bay. But in 1927, that saltworks was absorbed into the larger American company that became Leslie, which was bought by Cargill. The salt companies of the Turks were not big enough to compete.

A few miles south of Grand Turk Island, Salt Cay is a two-and-a-half-by-two-mile triangle with a sizable part of its interior occupied by abandoned salt ponds, crumbling rock coral dikes, brine still reddish with brine algae, abandoned metal windmills sticking out over the reddish water like homemade scarecrows. The airport is within walking distance of most of the population. Donkeys and cattle left over from better days wander wild, graze, and breed. The largest native animal in the arid, salty landscape is the three-foot-long giant iguana.

This island offers a chance to see a nineteenth-century Caribbean community. Livestock wander the streets. The tin-roofed whitewashed houses, shutters painted bright colors, their foundations surrounded by a row of conch shells, date mostly from the nineteenth century. There are almost no cars; it is mainly bicycles that use the well-worn sparkly roads that are paved with salt. In recent years, golf carts have been replacing bicycles as the leading mode of transportation. They seem well suited to the salt roads.

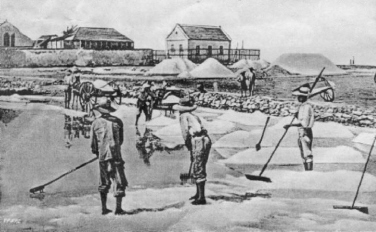

Under the rules of colonialism, everything goes to and comes from the mother country. In 1870, the colony of Turks and Caicos was asked to send a crest to England so that a flag for the colony could be designed. A Turks and Caicos designer drew a crest that included Salt Cay saltworks with salt rakers in the foreground and piles of salt. Back in England, it was the era of Arctic exploration, and, not knowing where the Turks and Caicos was, the English designer assumed the little white domes were igloos. And so he drew doors on each one. And this scene of salt piles with doors remained the official crest of the colony for almost 100 years, until replaced in 1968 by a crest featuring a flamingo.

In the nineteenth century, Salt Cay had 900 residents. In 1970, three years after the salt industry died, fewer than 400 remained. At the turn of the twenty-first century, 62 adults and 15 children were the only legal residents. Many of the 62 are retired, and the island would have a labor shortage were it not in the sea path between the island of Hispaniola and Florida. Many illegal Haitians and Dominicans land here, sometimes by mistake, and some find work and stay. If nothing else is available, money can always be made by taking rocks off the dikes and sea walls of the saltworks and sitting on the pile, smashing them one by one with a hammer into gravel for building material.

When the salt business died, the remaining merchants still had stockpiles of salt, often in the bottom floor of their homes. Eight- or nine-man Haitian sailboats arrived at the Turks and Caicos to sell mangoes and other items. Before returning home, they would stop off at the abandoned saltworks of South Caicos, Grand Turk, or Salt Cay, where mountains of salt remained, and scoop out a load.

The last powerful hurricane to hit Salt Cay, in 1945, destroyed all but three of the great houses where wealthy salt-trading families lived with their salt stored in the basement. In the late 1990s, one of the remaining three salt houses collapsed from termite damage, exposing its cache of salt. This unprotected, graying, and rain-eaten iceberg is the last of Salt Cay salt, except for a small crusty pile left slowly melting from humidity in the basement of one of the two great houses still standing.

An early twentieth-century postcard showing salt raking in Grand Turk.

Turks and Caicos National Museum, Grand Turk, B.W.I.

Native Salt Cay residents are called “belongers.” Many of the belongers were salt workers, who left for merchant marine service in World War II, stayed on until their retirement, and then returned home, not seeming to realize that in the meantime everyone else had left and the island had turned into a desert.

The trees had been cut for the saltworks, and without trees there was little rain and the earth dried out. The landscape is arid, with desert bushes clawing up from sandy, barren soil. Cattle and donkeys seeking the scarce shade from midday sun seem to be hiding silently behind every bush. The nights are starlit and cooled by an easterly breeze, with no sounds but the rolling sea and the occasional rustle of a wandering cow.

Adolphus Kennedy, born in 1915, lives on Salt Cay with his wife, who is three years younger. They are alone. Their four children and many grandchildren have all left. A soft-voiced man with a gentle manner, he recalls loading salt onto fourmasted schooners. Mostly he remembers the weight of the sacks. The pay?

“Oh, there was no pay. They paid us nothing. The big company kept all the money.”

It is easy to be romantic about the vanished Caribbean salt trade, but in truth it was similar to the history of sugarcane on other islands. Salt was built on slavery, and many thought that abolition in 1836 would mean the end of salt. But the salt merchants survived for a time because they could still get workers for near slave wages. There was no other work.

Most of the old belongers remember working for one shilling sixpence a day, less than a dollar. “That’s right,” said Kennedy. “One shilling sixpence for a nine-hour day.” He smiled. “But not every day. When ships were in and there was work. It was slavery,” he said, revealing no bitterness in his voice.

“Of course you could buy some food for a shilling. There was rain in those days, and they could use the land. Grew corn and beans and cucumbers.” Today, the land is too dry for such gardens. With no salt, little work, and less agriculture, the aged belongers live on government assistance. The Turks and Caicos is still a British colony.

The sluices are kept open and the ponds get seawater at high tides, so most are not evaporating. A few have evaporated into sand and salt crystal. In low tide, one of the canals that brings in seawater exposes two eighteenth-century cannons, weapons of war brought here to guard British salt from the Spanish, now rusting in the saltwater.

T

HE UNITED STATES

is both the largest salt producer and the largest salt consumer. It produces over 40 million metric tons of salt a year, which earns more than $1 billion in sales revenue. The production leaders, behind the United States, in order of importance are China, Germany, Canada, and India. France has fallen to eighth place and the United Kingdom to ninth.

But little of this is table salt. In the United States, only 8 percent of salt production is for food. The largest single use of American salt, 51 percent, is for deicing roads.

American salt sources are many and varied. The Great Salt Lake, which is the fourth largest lake in the world without an outlet, produces salt, some by Morton. Cargill operates a rock salt mine 1,200 feet below the city of Detroit. It covers more than 1,400 underground acres and has fifty miles of roads. The mine began with a disaster. In 1896, a 1,100-foot shaft was sunk but then became flooded with water and natural gas killing six and losing the investors their money. But in 1907, the mine was successfully started up.

Cargill also operates the mine on Avery Island. The McIlhenny and Avery families lease the salt mine to Cargill, the oil and gas to Exxon, and they still make the pepper sauce themselves. Paul McIlhenny, president and CEO, is the great-grandson of Edmund, who had come home from New Orleans with the seeds. He inherited Edmund’s robust round features and rugged friendly eyes. “We are lucky to be in a place that not only supports agriculture but has oil, gas, and salt,” he said.

Other books

Snow Melts in Spring by Deborah Vogts

Rescued by the Bad Boy (Bad Boys on Holiday Book 4) by Sylvia Pierce

A Closed Eye by Anita Brookner

Time for Love by Kaye, Emma

Plantagenet 1 - The Plantagenet Prelude by Jean Plaidy

Figure of Hate by Bernard Knight

All the Lasting Things by David Hopson

Oatcakes and Courage by Grant-Smith, Joyce

The Phantom in the Mirror by John R. Erickson

Philip Brennan 02 - The Creeper by Carver, Tania