Salt (66 page)

The agriculture he referred to is for Tabasco sauce, which has developed into a successful international family-owned business. The peppers grown today on Avery Island are only used for seeds that are planted in Central America, where pepper picking is still cost effective. Not only does the picking require skill, since each pepper must be picked at its moment of optimum ripeness, but it is painful, backbreaking work. The powerful capsaicin can burn hands, or if the picker is careless, the face and eyes. Experiments with machine harvesting failed, and the McIlhenny family refused to experiment with chemicals that would make all the peppers ripen simultaneously. So in the 1970s, when it started to become difficult to find people in southern Louisiana willing to pick peppers, the solution was to reverse history and take seeds from Avery Island back to Mexico and Central America every year.

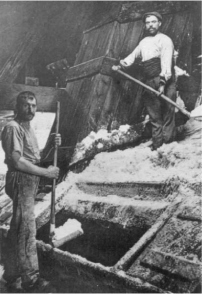

After one post–Civil War failure, salt mining began in earnest on Avery Island in 1898. Cargill took over in 1997. The current operation can mine nineteen tons of salt in a minute and a half and takes 2.5 million tons a year. Down in the mine more equipment is seen than actual miners. Bulldozers, tractors, jeeps, pickups, trucks, train carts, tracks, and other equipment are brought down piece by piece in a five-by-seven-by-ten-foot shaft elevator and assembled in the mine. Below, it looks like a busy nighttime construction site. A scaler, a huge machine that resembles a brontosaurus, steadily munches away at the white walls. When equipment is no longer useful, it is not considered cost effective to take it apart and bring it back up, so the mine leaves a trail of abandoned equipment, a junkyard on the side of some of the wide shafts. Salt mining has always been like that. The horses used in Wieliczka, and the mules lowered by rope underneath Detroit, never came back up either.

One of the older miners said that his father had worked fifty-two years under Avery Island, carrying salt blocks and loading them on mules. Today, the salt is trucked to crushers that break it into small enough pieces for the conveyor belts to move the salt to barges that carry it along the bayou and up the Mississippi River. A barge will hold 1,500 tons of salt.

The mine is dug in rooms called benches that are 60 feet by 100 feet with 28-foot ceilings. Once a bench is mined, a road is dug through the floor down to another level and another bench. The salt dome that is being mined is a column of solid sodium chloride, crystal clear, thought to be 40,000 feet deep—almost eight miles. The floors, the walls, the ceiling, and the uncut depths below are all between 99.25 and 99.9 percent pure. Under the miners’ lamps—the first miner’s safety lamp was invented by Humphry Davy—the benches appear to be black rooms. But a freshly cut bench, without the soot of machinery, is crystalline white, a room of pure salt crystal.

The vehicles are all four-wheel-drive, because the salt floor is as slippery as ice. Driving jeeps and trucks deep in the earth is like driving through a snow blizzard, at night. But it is darker than night. “It’s so dark it hurts your eyes,” one miner said.

The mine is currently operating at a depth of 1,600 feet, and with 38,400 feet to go, it might seem that this salt dome is an inexhaustible resource. But as the miners dig, to withstand added stress from the weight above them, the benches must be made smaller. Another problem is that salt is a good conductor of heat. The earth gets hotter closer to its center, and as they dig deeper into the earth the temperature will rise from the current ninety degrees. The heat will require more ventilation and more efficiency in machine-cooling systems. Also, the conveyor belt will get longer and longer. So the deeper they go, the more expensive the salt becomes, and salt must be cheap to be profitable. It is thought that the dome will offer another forty or fifty years of cost-effective mining, but that is a guess.

The salt is used for road deicing, industry, and pharmaceuticals. Table salt production stopped in 1982 when the energy cost of the vacuum evaporators was judged too costly. The Chinese might think that a salt dome full of oil and natural gas would have no problem with cheap energy, but in this case, the salt and the gas are operated by two separate companies that never arrived at the simple solution of ancient Sichuan.

In nearby New Iberia, a town canaled by bayous and draped in swaying moss, Avery Island salt used to be the salt of Cajun food. Ted Legnon’s father was a salt worker on Avery Island, and he brought home blocks of salt for boudin sausages and cured meat. Now Ted is a butcher, and he still makes boudin, though he now makes it without hog’s blood because the health department stopped the local slaughtering practices. He also uses Morton’s and not local salt.

One pound of salt is used for 250 pounds of boudin, along with ground pork meat, pork liver, cooked rice, onions, bell peppers, and powdered cayenne pepper. It is all stuffed in hog’s intestine and gently poached. Legnon’s Butcher Shop in New Iberia sells 300 pounds of this

boudin blanc

per day, except between Christmas and New Year’s, when sales rise to 500 pounds per day.

I

N RECENT YEARS

, scientists and engineers have been drawn to the ability of salt mines to preserve, because they usually have a low and steady humidity, and if not drilled too deep, an even, cool temperature. Also, salt seals. Crystals will grow over cracks. This was how the Celtic bodies had been sealed in the mine at Hallein. It is also why soy sauce makers formed a crust of salt on the top of the barrel, to make a perfect seal.

In March 1945, American troops passing through the German town of Merkers discovered a salt mine 1,200 feet underground. In it was 100 tons of gold bullion, twenty-nine rows of sacks of gold coins, and bails of international currency, including 2 million U.S. dollars. They also found more than 1,000 paintings, including Raphaels and Rembrandts. Among the booty were things of little value, such as the battered suitcases of people deported to concentration camps. The total value of the treasures, preserved in the perfect stable environment of a salt mine, was estimated at $3 billion 1945 dollars.

Because of the sealing ability of salt, it has also occurred to engineers that salt mines might be the safest place to bury nuclear waste. A Carlsbad, New Mexico, mine is being prepared for plutonium-contaminated nuclear waste that will remain toxic for the next 240,000 years. Salt will close over fractures, but how do we warn people 100,000 years from now not to open the mine? What language can be used? Suggestions include a series of grimacing masks.

The U.S. government has also stored an emergency reserve of petroleum in salt domes throughout the Gulf of Mexico area. The idea of a strategic oil reserve was first proposed in 1944. In the 1970s, it was decided to store at least 700 million barrels of oil in a select few of the 500 salt domes that have been identified in southern Louisiana and eastern Texas. But, ominous for the nuclear waste program, the domes don’t always seal. The Weeks Island salt dome, not far from Avery Island, was part of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve until signs of water leakage led to fear of flaws in the dome. The oil was pumped out and the dome abandoned.

T

HE OWNERS OF

the Dürnberg salt mine in Hallein, Austria, which has been hosting visitors since at least 1700, decided in 1989 that salt was no longer profitable and closed down the mine. But it still earns money from 220,000 visitors each year, taking them on rides on the steep, long wooden slides that were built to transport miners.

In the nineteenth century, when health spas became fashionable, many of the old brine springs saw a more lucrative alternative to making salt. In 1855, a bath was started at Salies-de-Béarn. In 1895, a red stone pseudo-Moorish palace was built to house the baths, which, in spite of continued salt production, became the town’s leading economic activity. The baths are said to be beneficial for gynecological problems, rheumatism, and children with growth problems. Today, only about 750 tons of salt are made in Salies-de-Béarn every year, but this is enough to ensure that the tradition of jambon de Bayonne continues.

Nineteenth-century salt making at Salies-de-Béarn.

Marcel Saule

The part-prenants are still organized and entitled to their share of the salt production, but today, rather than being paid in large buckets of brine, they are paid in money. Each of the 564 remaining part-prenants receives approximately thirty dollars per year.

The claim that millions of years ago, algae in the brine left bromides, iodine, potassium, and other minerals, is the basis of the town business in Salsomaggiore, outside of Parma. A spa palace was built from 1913 to 1923 by architect Ugo Giusti and decorator Galileo Chini. It is considered the greatest example of Liberty architecture, the Italian version of art nouveau. Marble columns line the halls, huge staircases climb to floors of marble mosaic with wicker furniture. Murals in gold leaf on the theme of water fill the huge, high-ceilinged walls.

The brine at the spa is said to be especially helpful to those suffering from rheumatism, arthritis, and circulatory ailments. Each year, 50,000 people go to Salsomaggiore to sit in a deep turn-of-the-century tub in a tiled room and be cured in brine like a herring.

The town is a collection of 1920s and 1930s hotels and cafes, resembling a faded, out-of-fashion Riviera resort without a beach. The well-dressed clientele arrive in trickles, not waves. The spa business has been struggling of late because the Italian government has stopped covering health spas in its national health plan.

Meanwhile, the famous prosciutto di Parma are now cured with salt from Trapani. A crossbred pig has been developed that has less fat and more weight, and it is still fed on the whey from Parmigiano cheese. The pig produces a huge, round, meaty leg. The designated area for prosciutto di Parma is about forty square miles, centered on the rolling, black-soiled farmland of Langhhirano, which means “lake of frogs,” originally a marsh. The popularity of these hams has turned prosciutto into a huge business, and the hundreds of thousands of hams produced every year are now cured in climatized rooms that derive no advantage from the dry winds.

Other books

Beyond the Rain by Granger, Jess

Found by Jennifer Lauck

The Point by Brennan , Gerard

Forever Beach by Shelley Noble

How Britain Kept Calm and Carried On by Anton Rippon

The Last Sundancer by Quinney, Karah

The Star King by Susan Grant

Promiscuous by Isobel Irons

Mudlark by Sheila Simonson

The Wild Card by Mark Joseph