Salt (54 page)

S

OME 3,000 YEARS

ago, wanting a capital in the commanding heights of the Judean hills, David conquered the fortress of Zion and built Jerusalem. Those heights have at times been a fortified high ground and at other times a peaceful gardened promenade. They offer, depending on the times, either a scenic or a strategic view of the region. Not only can a great deal of Israel be seen from here, but, on a clear day, the Moab mountains of Jordan are in view as a distant pinkish cloud. But what cannot be seen, because it is lower than the horizon—in fact, it is the lowest point on earth, 1,200 feet below sea level—is a vanishing natural wonder: the Dead Sea. The Hebrews called the sea Yam HaMelah, the Salt Sea.

About forty-five miles long and eleven miles at its widest, the Dead Sea, with the Israeli-Jordanian border running through the center of it, seems a peaceful place, of a stark and barren beauty. A first impression might be that the area is uninhabitable, and yet, like many of the world’s uninhabitable corners, it has been converted, with a great deal of water and electricity, into a fast-growing and profitable resort.

The minerals in the Dead Sea give a strange buoyancy that entices tourists for brief dips. The sea is oily on the skin and doesn’t feel like water. This is brine that will float more than an egg. After wading in a few feet, a human body pops to the surface, almost above the water, as though lying on an air-filled float. It is a most comfortable mattress, perfectly conforming to every part of the back—what a waterbed was supposed to be. The water, if it is water, is clear, but every swirl is visible in its syrupy density. The minerals can be felt working into the skin, and it feels as though some metamorphosis is taking place. The bather is marinating.

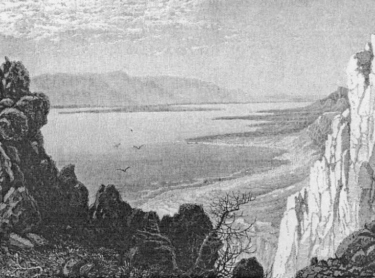

The Dead Sea from

Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt

(Volume 2) edited by Charles Wilson, 1881.

Pliny wrote: “The bodies of animals do not sink in it—even bulls and camels float; and from this arises the report that nothing sinks.” Edward Robinson, an American professor of biblical literature, reported after his 1838 trip, with no more hyperbole than Pliny, that he could “sit, stand, lie or swim in the water without difficulty.”

J

ERICHO, AN OASIS

a few miles north of the Dead Sea near the Jordan River, which flows to the Dead Sea, is thought to be the oldest town in the world. Almost 10,000 years ago, Jericho was a center for the salt trade. In 1884, in the nearby Moab Mountains of Jordan, the Greek Orthodox Church decided to build a church at the site of a Byzantine ruin in the town of Madaba. Workers uncovered a sixth-century mosaic floor map, still on display on the floor of the church of St. George, showing the Dead Sea with two ships carrying salt, heading toward Jericho.

But the sea may have been better for transporting salt than producing it. The oily water of the Dead Sea is bitter, as though it were cursed. The area is famous for curses, the most well known being the one that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah. The exact locations of Sodom and Gomorrah are unknown, but its residents are thought to have been salt workers and the towns are believed to have been located in the southern Dead Sea region. Since Genesis states that God annihilated all vegetation at the once-fertile spot, this barren, rocky area fits the description. But this area also has a mountain—more like a long jagged ridge—called Mount Sodom, of almost pure salt carved by the elements into gothic pinnacles.

According to the Book of Genesis, Abraham’s nephew, Lot, lived in Sodom and was spared when God destroyed the town, but Lot’s wife, who looked back at the destruction, was turned into salt. As columns break away from Mount Sodom, they are identified for tourists as Lot’s wife. Unfortunately, they are unstable formations. The last Lot’s wife collapsed several years ago, and the current one, featured in postcards and on guided tours, will go very soon, according to geologists.

In biblical times, Mount Sodom was the most valuable Dead Sea property. It was long controlled by the king of Arad, who had refused entry to Moses and his wandering Hebrews from Egypt. One of the most important trade routes in the area was from Mount Sodom to the Mediterranean—a salt route. Not far from Mount Sodom, in the motley shade of a scraggly acacia tree, are a few stone walls and the remnants of a doorway. They are the remains of a Roman fort guarding the salt route. A little two-foot-high stone dam across the wadi, the dry riverbed, after flash floods still holds water to be stored in the nearby Roman cistern.

The other source of wealth in the area besides Mount Sodom, which was mined for salt until the 1990s, is the Dead Sea. A body of water appears so unlikely in this arid wasteland cursed by God that in the afternoon, when the briny sea is a cloudy turquoise mirror reflecting pink from the Jordanian mountains, the water could easily be mistaken for a mirage.

Pliny wrote that “the Dead Sea produces only bitumen.” This natural asphalt was valued for caulking ships and led the Romans to name the sea Asphaltites Lacus, Asphalt Lake. Its water is 26 percent dissolved minerals, 99 percent of which are salts. This concentration is striking when compared to the ocean’s typical mineral concentration of about 3 percent.

The Judean desert, the below-sea-level continuation of the Judean hills, is a bone-white world of turrets and high walls, rising above narrow, deep canyons so pale they glow sapphire blue in the moonlight. The millions of small marine fossils embedded in the rock prove that this desert was once a sea bed, whose waters dried up in the heat that is sometimes more than 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

The seemingly barren desert hides life. There are said to be 200 varieties of flowers in the Judean desert, but they bloom only briefly and only by chance does a lucky wanderer ever see one. Graceful long-horned ibex, desert mountain goats, leap over rocks. Acacia trees, which grow in the wadis, have roots that grow as deep as 200 feet and contain salt to help them draw up the water hidden underground. A shrub known as a salt bush absorbs salt from the ground into its leaves so the leaves can soak up any moisture from the air.

The dry earth is actually laced with underground springs, some fresh, some brackish, which are easy to find because they are marked by small areas of vegetation. Each of these springs,

ein

in Hebrew and Arab, has its own history. This desert by a sea too salty to sustain life has attracted the margins of society. They have huddled along its life-giving springs: the adventurers, the pioneers, the dreamers, the fanatics, and the zealots. Many biblical references to going off “into the wilderness” allude to this area.

Across the Dead Sea, the barren, rocky, Jordanian desert is browner. The eight-mile-wide fertile strip of the Jordan Valley’s east bank feeds the nation. Israel, across the river, is the land of cell phones and four-wheel-drives. Here, farmers ride on donkeys, Bedouin ride on camels, some still living in their dark wool tents, their long dark gowns elegantly furling in the desert wind.

Jordanians sometimes call the Dead Sea “Lot’s Lake.” Mohammed Noufal, a pleasant, graying government employee, explained that, according to the Koran, it was made the lowest point on earth to punish Lot’s tribe for being homosexuals.

But if they were all homosexuals, how can they have descendants to punish?

Well, many were homosexuals.

T

HE CAUSE OF

the Dead Sea’s tremendous salinity has been the object of curiosity for centuries. In December 1100, after the knights of the first crusade made him ruler of what they termed the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, Baldwin I toured what is now the Israeli side of the Dead Sea. Fulcher of Chartres, who accompanied him, observed that the sea had no outlet and hypothesized that the source of its salt was minerals washing off of “a great and high salt mountain” where the Dead Sea ended to the south—Mount Sodom.

Several times in the eighteenth century, Dead Sea water samples were sent back to Europe for analysis. One such study was published by Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, the celebrated French chemist. A number of nineteenth-century American Protestant fundamentalists tried to study the Dead Sea, some through exploration and others by way of samples. Edward Hitchcock, who taught at Amherst, concluded through samples and biblical studies that the source of the sea’s salt was sulphurous springs some 125 miles away. Had he visited, he would have found brackish springs much closer.

In 1848, an American navy lieutenant, W. F. Lynch, reasoning that since the Mexican-American War was over, “there was nothing left for the Navy to perform,” persuaded his superiors to finance his own expedition to the Dead Sea. Two boats with hulls of corrosion-resistant metals, in itself a considerable technical advance at that time, were specially designed and carried overland from the port of Haifa to the Jordan River. Lynch and his team sailed down the Jordan River to the Dead Sea, which he found to be “a nauseous compound.” They continued sailing south for eight days and landed at the southern end of the sea. Lynch thought Mount Sodom to be not much of a mountain, which is true, and thought its composition to have a low percentage of salt, which is less true. Finding a broken-away column, he had a not particularly original thought: that it resembled Lot’s wife. When he analyzed a sample, he discovered that it was almost pure sodium chloride, which either proved the salt content of the mountain or confirmed the identity of the salt pillar.

Contemporary geologists still argue conflicting theories of why the Dead Sea is so salty. According to the most widely accepted of them, 5 million years ago the Dead Sea was connected to the Mediterranean near the current port of Haifa. A geologic shift caused the Galilee Heights to push up, and these newly formed mountains cut off the Mediterranean from the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea no longer received enough water to keep up with the rate of solar evaporation, and it began to get saltier.

This theory would explain why the sea is becoming more concentrated, slowly evaporating like a huge salt pond. It is already at the density at which sodium chloride precipitates, and salt has started crystallizing out on the bottom and the edges. Bathers gingerly step over sheets of icelike salt as they enter for a Dead Sea swim.

Other books

Letting You Go by Anouska Knight

Dear Lumpy by Mortimer, Louise

April 8: It's Always Something by Mackey Chandler

Love of a Marine (The Wounded Warriors Series Book 2) by Patty Campbell

The Land Across by Wolfe, Gene

A Real Job by David Lowe

The Estate Murder: A Cozy Mystery (The Witch Mysteries) by Kristal Wales

Murder in Wonderland by Leslie Leigh

Cold Burn by Olivia Rigal

Ghoul by Keene, Brian