Salt (50 page)

Cheshire salt makers had become skilled at making different products for an expanding and varied list of customers. Most of this simply involved adjusting the cooking time. Dairy salt was cooked fast, so that the rapidly moving water would create fine crystals used in butter and cheese. The large grains of solar-heated sea salt were replicated with the slow heating of so-called fourteen-day salt, which was shipped to Grimsby for salting cod. Salt hardened into blocks and then crushed was locally called “Lagos salt” because it was shipped to West Africa. Because the West African market bought salt by volume rather than by weight, all the Cheshire companies made a large, lightweight crystal for that market.

But in 1905, James Stubbs went to Michigan to learn about a new “evaporator.” The fundamental concept of a vacuum evaporator is that lower pressure reduces the boiling point of a liquid. A boiler produces steam, which heats a chamber, an evaporator. The steam is then piped into a second evaporator. The second evaporator cannot heat to as high a temperature, but because it is in a vacuum, the pressure is lower and less heat is needed for steam. This steam can then be passed to a third evaporator. And so an entire series of evaporators can be operated on the fuel that was expended to heat the first one. This solves one of the oldest problems in salt brine production, the problem the ancient Chinese solved with gas—the cost of fuel.

Liverpool sugar refiners had been using steam evaporators since 1823, when William Furnical had introduced the use of steam heat in sugar refining. In 1887, the first vacuum pan salt process was put in operation by Joseph Duncan in Silver Springs, New York. The evaporator heated brine to steam and forced it into a tank, where salt crystals formed; once the crystals reached a certain size and weight, they dropped through the bottom. If they were too big, they would be washed back up by the incoming brine; if too small, they would not drop down. For the first time in the long history of salt, a salt was being made in which every crystal was the same size.

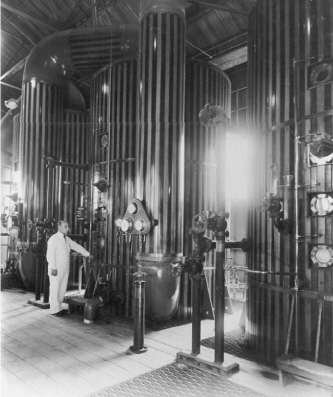

The Stubbses’s first vacuum evaporator.

New Cheshire Salt Works, Ltd., Northwich

The steam from the first tank was used to heat a second tank and a third tank. Today, up to six or even eight tanks, each evaporating brine, can be fueled by the first evaporating tank.

In the 1930s, the Stubbses finally imported their first salt evaporator to the New Cheshire Salt Works. This magnificent triple-towered machine was art deco in design, with vertical stripes of dark and blond wood and polished brass fittings and gauges. For a while, the Stubbses still had some open pans for larger crystal salt, but in time, the old pans could no longer compete economically with modern evaporators. New, more efficient evaporators were bought in the 1950s and again in the 1990s. The Stubbses, along with the Salt Union, are among only three surviving commercial British salt producers.

Anyone who makes bread in any quantity finds himself getting through a deal of salt. What salt then to use? Since with the exception of the famous Maldon salt from Essex on the east coast—again a luxury—there is now no sea salt extracted from English or Scottish waters, I use Cheshire rock salt sold in 11.2 pound blocks or 2 pound bags or 6 pound clear plastic jars, the latter being the best value and the most convenient. This salt is produced by the old Liverpool firm of Ingram Thompson (mention of “Liverpool salt” occurs quite often in eighteenth-and nineteenth-century cookery books) whose salt works are at Northwich. This firm’s packaging is minimal and their wholesale prices fair, so if you find you are paying too much for rock salt or “crystal” salt it is probably because middlemen have bought it in bulk and are charging retailers more than is fair.

—

Elizabeth David,

English Bread and Yeast Cookery,

1977

W

ITH BRINE WORKS

closing or sinking all around them, the Thompsons continued in the old ways. They sent salt blocks to Cheshire schools for children to make salt carvings. At Christmastime, workers still dipped branches into brine pans to grow crystals. In the 1960s, they were still employing hand riveters to mend their lead pans and a steam engine to bring up the brine. Then, in the late 1960s, Nigeria, the Thompsons’ principal remaining market, was destroyed by the Biafran war.

Many artisans have been faced with the choice of whether to industrialize or remain a small shop. But at a certain point that choice can be lost. If the operation becomes too unprofitable, it will no longer be able to attract the investment needed to modernize. This was the fate of the Thompsons. They hung on for more than a decade without making money; finally, in 1986, they gave up.

C

HESHIRE IS NOW

green English countryside. The pastureland is spotted yellow and purple with wildflowers and hedges over which blackberry vines twist. Reedy swan’s paddle grows in the unused canals. It is hard to believe that 100 years ago the sky was black with coal smoke, the horizon filled with a hundred smokestacks, the soil contaminated, arid, barren, and scarred white where the pan scale was dumped.

Local people write to the Thompson works and ask for the old salt, which was packed into wooden tubs and dried into salt blocks. They call it lump salt and say it is better for cooking beans and for curing meat. But there is no more Thompson salt.

The Vale Royal Borough Council bought the site and established a charitable trust, which is trying to make this last of the Northwich brine works a restored museum. It is struggling to get funding because sinkholes surround it. Black-and-white cows lazily nestle into the sinkholes, which are covered with grass and shrubs and delicate white Queen Anne’s lace. But every now and then, a little more subsidence is seen, something else sinks. Many believe that one day the old Thompson brine works will sink too.

T

WENTIETH-CENTURY INDIA

lived under the kind of colonial administration Madison and Jefferson had rejected—the kind that would have made Adams angry. And it did anger a great many Indians. To the British, the Indian economy existed for the enrichment of Great Britain. Industry was for the profit of the English Midlands. Indian salt was to be managed for the benefit

of Cheshire.

That the British always saw India as a commercial venture is demonstrated by the fact that when they first gained a foothold on the Asian subcontinent, they placed it in the hands of a private trading company, the Honourable East India Company. Founded in 1600 by a royal charter granted by Elizabeth I, the East India company, though a commercial enterprise, could function as a nation, minting its own money, governing its employees as it saw fit, even raising its own army and navy and declaring war or negotiating peace at will with other nations, providing they were not Christian. The company bought its first Indian property in 1639, a strip of coastline, and by the end of the century was building the city of Calcutta. A series of eighteenth-century battles between the British and the French eventually secured India for the British, who turned most of it over to the British East India Company.

The company established a sophisticated bureaucracy with a large, well-paid civil service. No high-ranking post was ever given to an Indian. By the nineteenth century, more than half of India was governed by the East India Company and the rest by local princes, who served as puppet rulers for the British. In 1857, Indians openly revolted, and the following year, once the British army had put down the rebellion, the British Crown took over most of the local government from the East India Company.

B

EFORE THE BRITISH

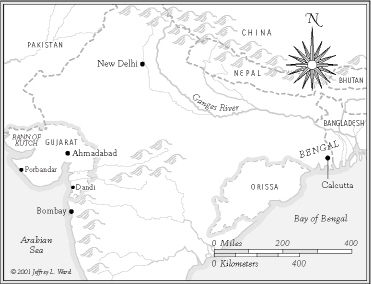

created artificial trade barriers, India had affordable, readily available salt. While it has huge saltless regions, with natural salt fields on both its coasts and huge rock salt deposits and salt lakes in between, India had an ancient tradition of salt making and trading. Although the extensive rock salt deposits in Punjab are unusually pure, strictly religious Hindus have always had a distrust of rock salt and even salt made from boiling. Indians have always preferred solar-evaporated sea salt not only for religious reasons but because it was more accessible. On the west coast, by what is now the Pakistani border, and on the east coast near Calcutta, river estuaries spread out into wetlands and marshes where the sun evaporates seawater, leaving crusts of salt.

On the west coast, in Gujarat, salt has been made for at least 5,000 years in a 9,000-square-mile marshland known as the Rann of Kutch. This marshland is covered by the sea and flooded rivers in the rainy season from August to September; in December, the salty water begins to evaporate with help from dry wintry winds from the north.

Other books

The Witch Queen's Secret by Anna Elliott

Miss Pymbroke's Rules by Rosemary Stevens

The Edge of Night by Jill Sorenson

Blue Dragon by Kylie Chan

The Coalition Episodes 1-4 by Wolfe, Aria J.

Cold Deception (His Agenda 4): Prequel to the His Agenda Series by Lavelle, Dori

Goddamn Electric Nights by William Pauley III

Secret Light by Z. A. Maxfield

When We Danced on Water by Evan Fallenberg

Fugitive Millionaire Revenge (Fabian Cooper Book Two) by Brooks, Jaclyn