Salt (49 page)

The strange sinkholes that had been sporadically appearing in the eighteenth century had become by the late nineteenth century a regular phenomenon—not so much in Nantwich, but in and around Northwich and Winsford. Every year new spots in meadows, pastures, and even towns collapsed. The holes caught rainfall and made small lakes. Toward the end of the century, a lake of more than 100 acres suddenly appeared near Northwich. Sometimes saltworks made use of the newly developed holes, filling them with ash or lime waste, just one more pollutant in an area black with coal smoke.

The brine makers tried to continue blaming the sinkholes on the rock salt miners, saying sinking was caused by abandoned mine shafts. This had worked better when rock salt was a new discovery. But in the nineteenth century, it became obvious that the location of the sinkholes bore no relation to the location of mine shafts, and as sinking became more frequent, there were not enough shafts to explain the number of occurrences. On the other hand, there was an exact correlation between the increase in brine production and the increase in sinkholes.

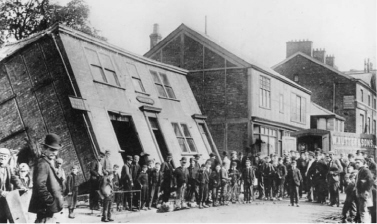

Subsidence: office buildings sinking in Castle, Cheshire.

The Salt Museum, Cheshire County Council, Northwich

The sinking was starting to wreak havoc with railroad lines and even to threaten bridges. In Northwich and Winsford, homes and buildings collapsed as the ground gave way underneath them. By 1880, 400 buildings had been destroyed or damaged in Northwich alone. At Winsford, a new church was condemned as dangerous. Water mains, sewer lines, and gas pipes were continually breaking, and the costs of repairing them were draining municipal budgets. Shop after shop was condemned and torn down.

A passing traveler described Northwich:

A number of miniature valleys seem to cross the road and in their immediate neighborhood the houses are, many of them, far out of the perpendicular. Some overhang the street as much as two feet, whilst others lean on their neighbors and push them over. Chimney-stacks lean and become dangerous; whilst doors and windows refuse to open and close properly. Many panes of glass are broken in the windows; the walls exhibit cracks from the smallest size up to a width of three or four inches; and in the case of brick arches over doors and passages, the key brick has either fallen out or is about to do so, and in many cases short beams have been substituted for the usual arch. In the inside, things are not much better. The ceilings are cracked and the cornices fall down; whilst the plaster on the walls and the paper covering it, exhibit manifold chinks and crevices. The doors either refuse to open without being continually altered by the joiner, or they swing back into the room the moment they are unlatched.—Chamber’s Journal,

1879

With an English flair for genteel euphemism, the growing disaster was labeled

subsidence.

Subsidence in Cheshire was becoming a subject of considerable amusement around England, spawning Cheshire jokes. But it also drew religious fanatics, who went to Cheshire to deliver sermons to the crowds who came to gawk at the holes. The preachers would stand at the edge of the craters looking down into akimbo boiling houses and broken smokestacks and warn that this was what hell would look like.

The truth was that too much brine was being pumped too rapidly from underneath Cheshire. Hundreds of ambitious small-scale entrepreneurs were making salt. They became extremely competitive. Some would pump additional brine out and dump it in the canals just to try to deprive their competitors.

The brine that flows over the salt rock of Cheshire is a saturated solution—one quarter salt—and so it is incapable of absorbing any more. But as brine was removed, fresh groundwater took its place, and this water would absorb salt until the brine was once again one-fourth salt. The problem was that if large quantities of brine were removed, they were replaced with large quantities of freshwater that hungrily absorbed considerable amounts of salt. Once that started happening, the freshwater began eroding the natural salt pillars that supported the space between the salt rock and the surface. When a pillar collapsed, the earth above it sank.

But even in the nineteenth century, when this process was understood, it was difficult to know whom to blame. The area around a saltworks might remain solid even though the brine it was pumping was causing the earth to collapse four miles away. Two or three other saltworks, though closer to the hole than the culprit, might have caused no damage at all.

Identifying the culprit was an important legal issue, since hundreds of people, many of them not in the salt industry, had lost their property and were demanding compensation. Unable to name a defendant, they could not pursue a legal action. Could they charge the salt industry in general? Citizens formed committees and went to Parliament proposing a bill that compensated victims for the damages caused by the salt industry. Property owners, citing a long-standing principle of British law that the owner of land owned the subsoil, claimed that not only was their property being destroyed, but they were being robbed of the rock salt that they owned. The brine pumpers were sucking up their rock salt from under their own sinking property.

The salt producers argued, with typical nineteenth-century capitalist confidence, that the locals were already being compensated by the economic benefits of having the salt industry. They denied that the subsidence was caused by pumping, insisting that the sinkholes were a natural phenomenon that would continue even without pumping. These arguments prevailed, and, in 1880, the bill was defeated.

I

N 1887, A

group of London financiers raised £4 million to buy up saltworks for a company called the Salt Union Limited. The company, founded by seven entrepreneurs without prior connections to the salt industry, wanted to buy up all British salt production and become the largest industrial company in England. Both the London

Times

and the

Economist

warned that such a giant could not maintain a monopoly on an industry whose raw material was so common and initial investment requirements so modest.

In Cheshire, with its long tradition of individualists and small private operators, many were angered at the sight of a corporate giant buying out local salt makers one by one. But industry leaders felt that the Salt Union was a workable solution to a sector that had too many participants. The rate of brine pumping spurred by this competition was in danger of literally sinking them all. The low salt prices of the late 1880s gave a further incentive to selling out.

Sixty-five salt producers sold out to the Salt Union. They were not only from Cheshire but from neighboring Staffordshire, Worcestershire, northeastern England, and Northern Ireland. The Salt Union had cornered 85 percent of British salt production. But most analysts believed that it had greatly overpaid to acquire these companies.

Nevertheless, the company was highly profitable its first few years, before going into a steep decline. Not until 1920 did profits again reach the level of 1890.

In 1891, when the Cheshire Salt Districts Compensation Bill again came before Parliament, the Salt Union used the arguments that the independent salt producers had used a decade earlier: that the people were being compensated by the economic benefits of having a salt industry and that the sinking was a natural phenomenon that would have occurred without saltworks. But now the Salt Union provided a target, a single entity that was clearly responsible—a defendant. The local citizenry spent a fortune promoting the bill, and both the Salt Union and its shareholders spent a fortune fighting it. It passed, though, and within ten years the Salt Union itself was applying for damages, saying its properties had suffered subsidence from the pumping of others.

In the long run, the Compensation Act probably helped the Salt Union. It created the Cheshire Brine Subsidence Compensation Board, which was financed by a flat tax on salt producers. The cost of the tax was onerous for small operations and insignificant for large ones. The small-scale producers regarded the Brine Board, as it was known, as another attempt by big salt to drive them out.

The Brine Board established a building code that had to be followed for new buildings to be eligible for compensation. The collapsing towns were rebuilt in the old Tudor style, with each new house resting on a timber frame that had built-in anchors for the placement of hydraulic jacks powerful enough to lift sinking buildings. An eighteen-inch lift looking like a canister was capable of hoisting fifty tons. It was the same technology that had been used to lift salt barges at the Anderton boat lift.

E

NGLAND IS SOMETIMES

thought of as a land of eccentrics who stubbornly cling to quaint and hopelessly outmoded ways, but it is also the land of entrepreneurs who created the Industrial Age. British industrialists built powerful companies, such as the Salt Union, that were the forerunners of today’s multinational giants. In Cheshire, these two kinds of Englishmen were represented by the Thompsons and the Stubbses.

Both families have long histories in Cheshire salt. A 1710 map marks “John Stubbs salt pit,” though today’s Stubbses do not know exactly who John was. Some Stubbses were dreamers. It was a Cheshire Stubbs who built a plantation in the Turks and Caicos Islands. But in the nineteenth century, the Stubbses joined the Industrial Age and sent their sons to school to study engineering.

The Thompsons were cursed with longevity. So while the Stubbses’ family operations were run by well-educated young engineers schooled in new technologies, the Thompsons’ family salt business was often run by octogenarian grandfathers and great-grandfathers.

Both families had saltworks near the sinking town of Northwich. Eventually, various members of the Stubbs family had salt-works all over Cheshire. But toward the end of the century, brine works, unable to compete with large companies, were one by one going broke, sinking either financially or literally. In the 1870s, various Stubbs brothers consolidated their operations, and in 1888, they sold out to the Salt Union.

After selling out and taking a seat on the board of directors, some of the brothers opened new saltworks across the county line. Then, in 1923, they bought the New Cheshire Salt Works near Northwich.

The Thompsons were not that different. In 1856, they started the Alliance Salt Works by digging a hole behind the Red Lion Hotel. But they too wanted to remain an independent family operation, and after they sold the Alliance Salt Works to the Salt Union in 1888, they dug a new shaft beside the Red Lion Hotel and called it the Lion Salt Works. New technology had concentrated on finding salt and bringing it to the surface. But once the brine reached the saltworks, little had changed since the time of the Romans. It was still evaporated in lead pans. The pans had gotten larger than the three-by-three-foot Roman ones. The Thompsons had thirty-by-twenty-foot lead pans, heated by coal that was stoked from four furnace doors in the huge coal oven under the pan. Into the nineteenth century, even the pipes for brine were still made from hollowed tree trunks. Except for larger pans and coal being burned instead of wood, most of the process was described in Georgius Agricola’s 1556 work

De re metallica

, which remained the standard European text on salt making. The work was first translated into English in 1912 by mining engineer and future U.S. president Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou Henry Hoover.

Other books

The Apartment by Danielle Steel

Sir Tristan's Estate (Legends Unleashed Vol.1) by Heather Beck

Kepler by John Banville

Holiday With Mr. Right by Carlotte Ashwood

Meet Me in Barcelona by Mary Carter

Curse of the Mummy's Uncle by J. Scott Savage

Territorio comanche by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

FOUR PLAY by Myla Jackson

Desire in the Sun by Karen Robards

Brush with Haiti by Tobin, Kathleen A.