Salt (44 page)

A nineteenth-century photograph of a windmill pumping brine into a saltworks in south San Francisco Bay.

The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

The first discouraging surprise was that only fifteen camels survived the cross-Pacific voyage to California. The survivors arrived in such bad condition that it took Esche months to nurse them back to good health. They carried salt across the mountains, but the strange, furry, long-legged creatures were not well received in Nevada.

The silver miners can be added to a long list of novices who have found that camels, even the better-tempered Bactrians, can be disagreeable. They bite, spit, and kick. The miners hated them, as did their horses and mules, who became hysterical at the sight of them. This reaction by the other animals made the camels a public nuisance. A few would lope into town, and suddenly the street was alive with neighing, braying, and kicking. Virginia City, Nevada, passed an ordinance outlawing camels on the town streets except between midnight and dawn, when, presumably, the other animals were in stables resting. Eventually, to the relief of the miners, Esche gave up on the camels and released them in the Nevada desert to thrive on their own. Since no camel colony has ever been discovered there, it is assumed they all died, probably a slow, pitiful death.

I

N THE SPRING,

seawater was pumped into the ponds of the south bay. Through the summer, the brine would be moved; by late summer, it was dense enough to crystallize. The brine turned pink and then a dark brick color. Today, when people fly into San Francisco, they sometimes gaze out the window and wonder about the pink-and-brown geometric ponds at the end of the bay.

The color is a common phenomenon that had previously been observed in Europe, in the Dead Sea, and in China, among many other places that made sea salt. Both Strabo and Pliny wrote about this curious color in brine that later disappeared after crystallization. Strabo, who pondered the color of parts of the Red Sea, thought it was caused by either heat or a reflection.

In

Salt and Fishery, Discourse Thereof,

Collins had mentioned the phenomenon, attributing the color to red sand. The red color was generally thought to be an impurity that could cause spoilage, and it was believed that it might turn the fish or meat red and then the food would soon spoil. In 1677, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, the Dutch naturalist who made numerous discoveries with a crude microscope, concluded that the red color was caused by microorganisms in the brine.

Whatever the cause, the simple observable fact, as Denis Diderot pointed out in his eighteenth-century encyclopedia, is that “you know the salt is forming when the water turns red.”

Charles Darwin observed the phenomenon in Patagonia:

Parts of the lake seen from a short distance appeared of reddish color, and this perhaps was owing to some ifusorial animalcula. The mud in many places was thrown up by numbers of some kind of worm, or annelidous animal. How surprising it is that any creatures should be able to exist in brine.

In 1906, E. C. Teodoresco identified a one-celled plant called dunaliella, which most observers concluded must actually be two species because the brine initially developed a green scum and only later, when more dense, turned red. Were there both green and red dunaliella? Darwin wrote of the complex ecology of sea saltworks where single-celled algae lived in brine and turned it green, but at a denser level, tiny shrimp and worms turned it red, and these reddish animals attracted flamingos, which turned pink from eating them. In fact, Darwin had figured out the entire mystery in the nineteenth century, but few listened to him until well into the twentieth century.

The San Francisco Bay salt makers of the silver rush days believed the dark red color came from insects in the brine. Only in modern times has it been understood that dunaliella is green, but once the brine reaches a certain level of salinity, it turns red. In addition, tiny, barely visible shrimp, brine shrimp, live in the brine at this density. And there are also salt-loving bacteria of reddish hue that are attracted to brine. Not only does the red color signal that the brine is ready, it intensifies the solar heat and hastens evaporation, helping the salt to turn to crystals and fall out of the reddish water. Today, the saltworks of San Francisco Bay sell their reddish little creatures to other saltworks that wish to improve their evaporation process.

Just as Diderot had observed but could not explain, when the brine reaches the density that attracts these shrimp, algae, and bacteria, it means that the brine is at a density close to the point of crystallization. The process of making salt, though practiced since ancient times, was beginning to be understood.

It is an old remark, that all arts and sciences have a mutual dependence upon each other. . . . Thus men, very different in genius and pursuits, become mutually subservient to each other; and a very useful kind of commerce is established by which the old arts are improved, and new ones daily invented.

—William Brownrigg,

The Art of Making

Common Salt,

London, 1748

E

DMUND CLERIHEW BENTLEY

, a British author of crime novels who lived from 1875 to 1956, wrote these lines, it is said, while in a chemistry class:

Sir Humphry Davy

Abominated gravy.

He lived in odium

Of having discovered sodium.

This was the first of a verse type known as a clerihew, which is a pseudo-biographical verse of two rhymed couplets in which the subject’s name makes one of the rhymes. It became a genre of humorous poetry, although not many people can recite another example of a clerihew.

Sir Humphry Davy was also an Englishman, born in 1778, and a largely self-taught chemist. When he was a twenty-year-old apprentice pharmacist in Cornwall, the Pneumatic Institution of Bristol offered him a job researching medical uses of gases, which may have been a twenty-year-old’s dream job. There is little evidence of his feelings about gravy, but he was known to have a great fondness for nitrous oxide, laughing gas, which he experimented with at length and found to be not only an enjoyable recreational drug but a cure for hangovers. Notable friends, including the poets Robert Southey and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, shared in the experiments. But Davy learned that some gases are better than others, and he almost died from his experiments with carbon monoxide.

Davy’s work in Bristol came under attack by conservative politicians, including the famous Irish MP Edmund Burke, who accused the gas experiments of promoting not only atheism but the French Revolution.

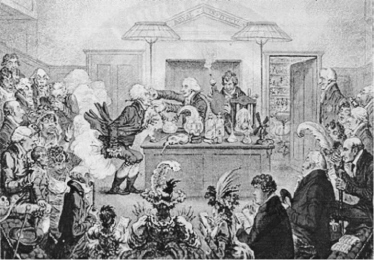

Young Humphry Davy merrily mans the bellows in a laughing-gas experiment being presented by his predecessor at the Royal Institute, Benjamin Thomas, in a caricature by James Gellray.

The Chemical Heritage Foundation, Philadelphia

But within a few years, his other experiments with electrolysis, passing electricity through chemical compounds to break them down, earned him enduring fame. Davy’s chemistry lectures at the Royal Institute became so noted for the brilliance of his delivery that the talks were regarded as fashionable cultural events. Then, in 1812, to the disappointment of fans, he married a wealthy widow and gave up lecturing to spend his time touring Europe.

Davy, a brilliant scientist, had a flair not only for performance and for living well, but also for self-promotion. He managed to garner credit for a phenomenal number of the scientific breakthroughs of his day. Through electrolysis, he was able to isolate for the first time a number of elements, including, in 1807, sodium, the seventh most common element on earth. This discovery was the first important step toward at last understanding the true nature of salt.

T

HAT DIFFERENT TYPES

of salt existed and were suited for different purposes was a very old idea. The ancient Egyptians knew the difference between sodium chloride and natron. But they didn’t understand their composition or how to make them. Saltpeter, which can be sodium nitrate or potassium nitrate, was well known by the medieval Chinese, who used it for gunpowder. After Europeans learned about gunpowder, the market for potassium nitrate seemed limitless. But little was known about its properties.

As early as the sixteenth century, nitrates were used in cured meats to make them a reddish color, that was thought to be more in keeping with the natural color of meat. In fifteenth-century Poland, game was preserved in nitrate simply by gutting the animal and rubbing the cavity with a blend of salt and gunpowder, which was potassium nitrate. It took centuries of use before anyone understood how potassium nitrate and its cheaper cousin, sodium nitrate, which is often called Chile saltpeter, are broken down by bacteria during the curing of meat. The nitrate turns to nitrite, which reacts with a protein in the meat called myoglobin, producing a pinkish color. The reaction also produces minuscule amounts of something called nitrosamines, which may be cancer-causing. Today, the amount of nitrates is limited by law to what seems to have been deemed an acceptable risk for the oddly unquestioned goal of making ham reddish.

For centuries, different types of salts were recognized by taste. The Great Salt Lake was clearly a concentration of sodium chloride because it had a pleasant salty taste, whereas the “bitter nauseous” taste of the Dead Sea indicated magnesium chloride. The long practiced principle of evaporating brine was that when brine becomes supersaturated—when it is at least 26 percent salt, which is considerably more than the 2.5 or 3 percent salt of seawater—sodium chloride crystalizes and falls out, or precipitates, from the liquid. But slowly it was discovered that after the sodium chloride, the salt of primary interest, precipitates, a variety of other salts crystalize at even denser saturation.

Other books

Forever Starts Tomorrow by Ellen Wolf

Einstein's Monsters by Martin Amis

Sons of Abraham: Terminate by Ray, Joseph

Passion Awakened by Jessica Lee

Lover by Wilson, Laura

The Adventures of a Love Investigator, 527 Naked Men & One Woman by Silkstone, Barbara

An American Dream by Norman Mailer

The Carpet People by Terry Pratchett

Twice in a Lifetime by Dorothy Garlock