Salt (43 page)

McIlhenny’s wife, Mary Eliza Avery, left a handwritten collection of recipes. Since she used her maiden name on the front page, the collection can be dated before 1859, the year of her marriage. In this collection of Cajun and southern Louisiana recipes, numerous dishes call for “red pepper and salt.”

SHRIMP GUMBO

Take a chicken and cut it up as for a fricassee. Put in your soup pot a spoon full of lard, when hot stir in two table spoons full of flour until it becomes a lite brown color; chop fine a large onion, and throw into the flour and lard with the chicken, stirring it until the chicken becomes slightly cooked. Add boiling water as [appropriate?] for a soup stirring well. Put in red pepper and salt to your taste, with a bunch of parsley and thyme (this preparation can be made of shrimp as well as chicken). Take 4 or 5 pints of shrimps and pour boiling water on them when they first come from market. Take the meat and the roe from the shells. Put the heads and shells into a stirr-pan, covering them with boiling water. Mash them so as to extract the juice—strain it and add the liquid to the soup. About 15 minutes before sending to table throw in the Shrimps. When ready to serve the soup, stir in a large tablespoonful of fresh Fillet and turn immediately into the tureen.—

Mary Eliza Avery

McIlhenny started his pepper sauce experiments with a variation on a sauerkraut recipe, using salt to ferment and extract juices from fresh crushed peppers. He quickly learned that he had to use the ripest peppers, picking each of the fruits of his annual plant at its optimum moment, when it was the brightest red. Stirring half a cup of his own Avery Island salt into each gallon, he aged the mixture, trying pickling jars and then pork barrels. He covered the lids with salt, which, when mixed with the juices of the fermenting peppers, sealed the barrel with a hard crust, by chance the same way the Chinese had been aging bean mash for soy sauce for thousands of years.

Up to this point, it was an all-Avery-Island product, made with the island’s salt and peppers. In much of the South, the Caribbean, and Mexico, this would constitute a hot sauce. But the New Orleans tradition called for vinegar. McIlhenny strained the mash after it had aged for one month, and mixed it with French white wine vinegar. Then he put it in small cologne bottles, which he sealed with green wax. Each bottle came with a little sprinkler attachment that could be placed in the opening after the seal was broken.

McIlhenny had a shed on Avery Island that he called his laboratory, a place with a sweet pungent smell that tickled the nostrils and made passersby want to sneeze. He would let his children leave school early to help him in the laboratory.

In 1869, he produced 658 bottles and sold them for the handsome price of one dollar each wholesale in New Orleans and along the Gulf. People used the sauce as a seasoning in recipes that called for red pepper and salt. In 1870, he obtained a patent and named the concoction Petite Anse Sauce. His family was appalled that he was commercializing the historic family name for his eccentric project. So he settled for Tabasco sauce, after the Mexican state on the Gulf known for hot peppers, possibly even the area where the mysterious Gleason had obtained the original peppers.

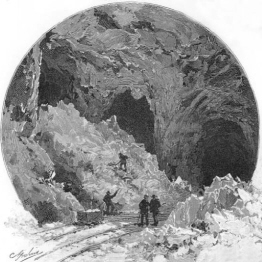

April 28, 1883,

Harper’s Weekly

drawing of salt mining under Avery Island.

These were not lucrative years on Avery Island. An attempt to return to salt mining was a failure. By 1890, when Edmund McIlhenny died at age seventy-five, he had built a modest family business with Tabasco sauce, though nothing compared to the fortune he had earned in useless currency from two years of wartime salt.

A

FTER THE CIVIL

War, while pepper sauce was looking more lucrative than salt in Louisiana, the American West offered dramatic opportunities. The West was rich in precious minerals and in salt, which was still used to purify ore, especially silver.

The most spectacular salt strike in North America was found in a shrinking glacial lake in Utah. In the eighteenth century, the Spanish, while searching Utah for gold and silver, had been told of a huge salt lake. But they never saw it. The first record of anyone of European origin seeing the Great Salt Lake was in 1824 by James Bridger, a hunter, trapper, and explorer who was the prototype of the legendary “mountain man.”

In Carthage, Illinois, in 1846, an angry mob assassinated Joseph Smith, the leader of a new religious group known as the Mormons. Brigham Young, who took Smith’s place, wanted to find a new land where Mormons could set up their own community away from the scrutiny of other Americans. In search of a place with natural resources, so that his isolated group could have economic self-sufficiency, he chose this Great Salt Lake in the middle of a desert that at the time belonged to Mexico. The lake had no outlet and contained highly concentrated brine. Next to it was one of the largest sebkhas ever found—a flat, thick, 100-mile-long layer of salt, which became a mainstay of the Mormon economy.

Other salt beds were found in the West, but none so large or with as pure a concentration of sodium chloride as the Great Salt Lake area, the remains of a far larger 20,000-square-mile prehistoric lake geologists call Lake Bonneville.

But the real need for salt lay farther west in Nevada and California, where silver was found. Relatively close to these silver strikes was one of the oldest saltworks in the American West.

The southern end of San Francisco Bay is an insalubrious marshland with ideal conditions for salt making. Not only does it have more sun and less rainfall than San Francisco and the north bay, but it has wind to help with evaporation. The intensely hot air from central California comes over the mountains, and the temperature difference sucks in the cool sea breeze.

This is why centuries and perhaps millennia before the California and Nevada silver strikes, a people called the Ohlone made annual pilgrimages to this area for salt making. At the water’s edge, the brine slowly evaporated in the sun and wind and left a thick layer of salt crystals. They had only to scrape it. The first European to notice the local salt making was a Spanish priest, José Danti, who explored the eastern side of the bay in 1795. In the southern end of the east bay, he found marshes with thick layers of salt, and “the natives,” he reported, told him that it provided salt for much of the area.

The Spanish were content to let the Ohlone produce salt. They only wanted a share—a very large one—of the profits. To this end, they forced the Ohlone to turn all their salt over to the Spanish missionaries who controlled distribution. The only technology added by the Spanish was to drive stakes into the ground at the water’s edge to offer additional evaporation surfaces.

In 1827, Jedidiah Smith, one of the earliest U.S. citizens to settle in California, arrived in San Francisco Bay and noted that “from the Southeast extremity of the bay extends south a considerable salt marsh from which great quantities of salt are annually collected and the quantity might perhaps be much increased. It belongs to Mission San Jose.”

After California became a state in 1850, a San Francisco dockworker named John Johnson became interested in this salt area. At age thirty-two, his life story was already a popular legend. Supposedly, he had lost both parents in a fire from which he was saved as a baby in Hamburg, Germany. He went to sea at thirteen and was one of two hands that survived on a sinking ship by perching on top of the highest two masts for twelve hours. He was said to have been a sealer, a whaler, and a slaver—a ruthless adventurer who would try anything to make money. When he learned about the southeast part of the bay, he decided to try salt.

At first, Johnson was able to charge extremely high prices and make tremendous profits. But this was the time of the gold rush, and adventurers from all over the world were coming to the Bay area looking for quick profits. Many followed Johnson to the south bay. Soon abundance caused the price to crash.

San Francisco Bay salt was considered of low quality, and it did not compete easily with Liverpool salt, which came as ballast on the British ships that bought California wheat. Coarse salt was also regularly imported from China, Hawaii, and numerous places in South America.

But in 1859, something happened that drove salt prices back up. In western Nevada near the California border, a three-and-a-half-mile stretch of the Sierra Nevada mountains was found to hold the richest vein of silver ever discovered in the United States. It was called the Comstock lode, named after an early investor who had sold out before the extent of the vein was known. The silver ore was being separated by a technique similar to the sixteenth-century Mexican patio process, and it required mountains of salt.

By 1868, only nine years after the discovery of the Comstock lode, eighteen salt companies were operating in the south bay. To keep the profit margin high, the salt was mostly harvested by Chinese laborers, the cheapest source of labor in California at the time. The salt workers wore wide wooden sandals to avoid sinking in the thick layer of white crystals.

After a few years of scraping, the area was running out of naturally evaporated salt, and the salt producers started building successive artificial ponds, pumping the water from one pond to the next by the power of windmills.

Fortunes were being made on the silver in Nevada and on the salt in California. Then, in 1863, a man named Otto Esche came up with a scheme to make money on the link between them. The salt was shipped inland and into the Sierra Nevadas in horse-drawn carts. Esche went to Mongolia, even today one of the more remote corners of the earth, and bought thirty-two Bactrian camels. Esche apparently knew something of camels since he chose the more docile two-humped camel rather than the notoriously temperamental dromedary of the Middle East. Bactrian camels, since before Marco Polo’s time, had been carrying goods, including salt, across the brown, wide, Mongolian desert.

Other books

Superfluous Women by Carola Dunn

Hell's Geek by Eve Langlais

Muse (Tales of Silver Downs Book 1) by Kylie Quillinan

All Jacked Up by Desiree Holt

Fractured Fairy Tales by Catherine Stovall

Bolt Action by Charters, Charlie

Billion Dollar Baby Bundle 2 by Simone Holloway

The Mist by Carla Neggers

Ghosts of Infinity: and Nine More Stories of the Supernatural by Lara Saguisag, April Yap

Entitled: A Bad Boy Romance (Bad Boys For Life Book 1) by Slater, Danielle, Sinclaire, Roxy