Salt (39 page)

Kanawha served this midwestern market with little competition. Unlike the French and the Spanish, English settlers and their American descendants tended to bring salt with them rather than find it where they went. In a market-driven society, a distant but efficient saltworks with good transportation seemed a more practical solution than a nearby but inefficient saltworks. As Americans moved west, they shipped salt from the East, just as the settlers in the East had shipped it from England.

Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky saltworks, many of them adapted by the French from the saltworks of indigenous people, had weaker brine than Kanawha and used wood rather than coal. This made Kanawha salt far cheaper to produce. In fact, even at outrageously inflated prices, Kanawha salt makers could still undersell their competitors, not only because of the density of their brine but because their workers were slaves.

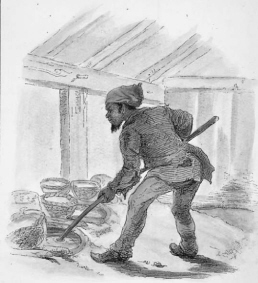

A wood engraving of a slave working in a Virginia saltworks.

The Granger Collection

Kanawha was in the state of Virginia, which had a huge slave-based tobacco industry that was slowly declining. The large tobacco plantations had more slaves than they could use, and the owners saw an economic opportunity in renting these people to Kanawha salt producers. According to the 1810 census, Kanawha county had 352 slaves, but by 1850, 3,140 slaves lived in the county, mostly assigned to saltworks.

By law the saltworks could only require slaves to work six days a week, but this law was seldom enforced. The best job for a slave at the saltworks was barrel maker. The salt was shipped in barrels, and slaves were expected to make seven barrels a day. Sometimes owners who rented their slaves would negotiate better terms such as only six barrels being required a day. The worst job in the salt-works, and one almost exclusively done by slaves, was coal mining. Slave owners would sometimes stipulate that their slaves were not to be used as coal miners, arguing that it was a misuse of their valuable property. Coal miners were often maimed or killed in cave-ins. The saltworks themselves were also dangerous, especially for slaves who were not trained in this industry. Boilers exploded, and sometimes workers would slip into near-boiling pots of brine. The owners sometimes sued the salt makers to be compensated for the loss or damage of their human property.

Plantation slaves did not want to be leased to saltworks, and they would sometimes escape while being taken west. The slaves knew that, like the salt, they were only a short journey to Ohio, which was a free state. Many slaves escaped by land or water, and salt makers would hire men to go to Ohio and bring them back. Once steamboats appeared, runaways increased, in part because of the transportation the boats afforded and in part because the boats hired free blacks who would encourage escape. Even the slaves who worked on the boats clearly lived a better life than the slaves in Kanawha.

In January 1835, Judge Lewis Summers complained, “There seems to be some restlessness among the slaves of the salt works and I thought more uneasiness in relation to that species of property than usual.”

R

OBERT FULTON DID

not invent the steamboat, though he did build one of the first submarines,

The Nautilus,

which the French, British, and American governments all rejected. Fulton’s enduring fame comes from a steamboat he launched in New York harbor in 1807 that sailed the Hudson. Numerous earlier steamboats had been built, and in 1790, John Fitch had established the first steamboat service, ferrying passengers between Philadelphia and Trenton. But such experiments were all commercial failures. Robert Fulton’s Hudson River boat made money and demonstrated for the first time the commercial viability of steam-powered, flat-bottom, paddle-wheel-propelled riverboats.

These boats created Kanawha’s first real competition. By the 1820s, steamboats for the first time made Liverpool salt accessible in the U.S. interior because they had enough power to carry a heavy salt load upriver against the strong currents of western waterways. The British liked to carry salt as ballast for their cotton trade with New Orleans, and they landed Liverpool, Turks, and Salt Cay salt there. The new steamboats carried foreign salt up the Mississippi River system, including the Ohio. The shallow-hulled steamboats could even navigate past the falls of the Ohio at Louisville, which had previously excluded Madison and Cincinnati from Mississippi traffic.

While this was happening, the Erie Canal opened, providing Syracuse with a western waterway. Before the Erie Canal, Onondaga salt had to be carried by pack mule to Lake Erie. The New York salt was preferred by many because, as with French bay salt, the slow solar evaporation process produced a desirable coarse grain. But because of slavery and ample nearby coalfields for fuel, Kanawha salt was cheaper.

No sooner was the Erie Canal opened than other canal projects were proposed. The first one was started in 1832: a 334-mile artificial waterway called the Trans-Ohio Canal, from the Ohio River to Cleveland on Lake Erie. Salt was the only bulk commodity transported on the Trans-Ohio Canal. By 1845, canals also connected Onondaga salt to the Wabash in Indiana.

The Erie Canal offered a refund on tolls to New York State salt producers if they used the canal to carry salt out of state. In trade on the Great Lakes, salt became ballast where empty ships had previously been weighted with sand. Sometimes they would carry the salt for free. By the 1840s, Syracuse, not Kanawha, became the leading supplier of salt in the Midwest.

I

N THE 1840S,

the Kanawha salt makers received another blow. The protective tariffs against imported salt designed to stimulate domestic salt production after the Revolution were angering westerners because they raised the price of salt. In their view, by taxing imported salt, the government was allowing domestic producers to overcharge. Kanawha, in particular, was the salt producer singled out for this accusation.

In 1840, Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton delivered a speech in the U.S. Senate comparing Kanawha salt makers to the British East India Company, a despised instrument of British colonialism, the economic system that Americans had fought two wars against.

The tax on foreign salt, by tending to diminish its importation, and by throwing what was imported at its only seaport, New Orleans, into the hands of regraters, this tax was the parent and handmaiden of a monopoly of salt, which, for the extent of territory over which it operated, the number of people whom it oppressed, and the variety and enormity of its oppressions, had no parallel on earth, except among the Hindoos, in Eastern Asia, under the iron despotism of the British East India Company. . . . The American monopolizers operate by the moneyed power, and with the aid of banks. They borrow money and rent the salt wells to lie idle; they pay owners of the wells not to work them; they pay other owners not to open new wells. Thus, among us, they suppress the production, by preventing the manufacture of salt.—

Thomas Hart Benton, U.S. Senate, April 22, 1840

Among the opponents of Senator Benton in the Senate was the delegation from Massachusetts, which desperately wanted to preserve the tariffs. But by the end of the decade the tariffs were removed, and not only Kanawha but also Cape Cod could no longer compete.

By 1849, when Henry David Thoreau visited the Cape, he was already writing about saltworks being broken up and sold for lumber. Those boards, used to build storage sheds, were still leaching salt crystals 100 years later. By then the Cape Cod salt industry was long vanished.

Kanawha survived. Soon the country would be divided into North and South, and it would become apparent that a southern saltworks was an important and all too rare asset.

I

N THE 1939

classic film of the Civil War,

Gone With the Wind,

Rhett Butler sneered at southern boasts of imminent victory, pointing out that not a single cannon was made in the entire South. But the lack of an arms industry was not the only strategic shortcoming of the South. It also did not make enough salt.

In 1858, the principal salt states of the South—Virginia, Kentucky, Florida, and Texas—produced 2,365,000 bushels of salt, while New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania produced 12,000,000 bushels.

By 1860, the United States had become a huge salt consumer, Americans using far more salt per capita than Europeans. Numerous saltworks had sprung up in the North. Onondaga, the leading salt supplier, reached its peak production during the Civil War. The 200 acres of vats in 1829 had expanded to 6,000 acres by 1862, when it employed 3,000 workers and produced more than 9 million bushels of salt.

The United States as a whole was still dependent on foreign salt, but most of those imports went to the South. The imports from England and the British Caribbean were landed in the port of New Orleans. One quarter of all English salt entering the United States came through New Orleans. From 1857 to 1860, 350 tons of British salt were unloaded in New Orleans every day, ballast for the cotton trade.

As generals from George Washington to Napoléon discovered, war without salt is a desperate situation. In Napoléon’s retreat from Russia, thousands died from minor wounds because the army lacked salt for disinfectants. Salt was needed not only for medicine and for the daily ration of a soldier’s diet but also to maintain the horses of a cavalry, and the workhorses that hauled supplies and artillery, and herds of livestock to feed the men.

Salt was always on the ration list for the Confederate soldier. In 1864, a soldier received as a monthly allowance ten pounds of bacon, twenty-six pounds of coarse meal, seven pounds of flour or hard biscuit, three pounds of rice, one and a half pounds of salt—with vegetables in season. But the Confederate ration list was in reality a wish list that was only occasionally realized.

Other books

2nd Chance by Patterson, James

Knockout! A Passionate Police Romance by Emma Calin

Heart of the Outback by Emma Darcy

Alphas & Millionaires Starter Set by Brooke Cumberland

En busca del rey by Gore Vidal

Magic in the Stars by Patricia Rice

A Lie About My Father by John Burnside

Two Masters for Alex by Claire Thompson

Letters to a Young Scientist by Edward O. Wilson