Salt (18 page)

Robert May, a cook for the Royalists in turbulent seventeenth-century England, suggested salt cod be made into a pie.

Being boiled, take it [the salt cod] from its skin and bones, and mince it with some pippins [apples], season it with nutmeg, cinnamon, ginger, pepper, caraway-seed, currans, minced raisons, rose-water, minced lemon peel, sugar, slic’t [sliced] dates, white wine, verjuice [sour fruit juice, in this case probably from apples], and butter, fill your pyes, bake them, and ice them.

—

Robert May,

The Accomplisht Cook,

1685

Though cod is found only in northern waters, salt cod entered the repertoire of most European cuisine, especially in southern Europe where fresh cod was not available. The Catalans became great salt cod enthusiasts and brought it to southern Italy when they took control of Naples in 1443. The following recipe comes from the earliest known cookbook written in Neapolitan dialect.

BACCALÀ AL TEGAME

[PAN-COOKED SALT COD]

Always select the largest cod and the one with black skin, because it is the most salted. Soak it well. Then take a pan, add delicate oil and minced onion, which you will sauté. When it turns dark, add a bit of water, raisins, pine nuts, and minced parsley. Combine all these ingredients and just as they begin to boil, add the cod.

When tomatoes are in season, you can include them in the sauce described above, making sure that you have heated it thoroughly.—

Ippolito Cavalcanti (1787–1860),

Cucina casereccia in dialetto Napoletano,

Home cooking in Neapolitan dialect

A

LL OF THE

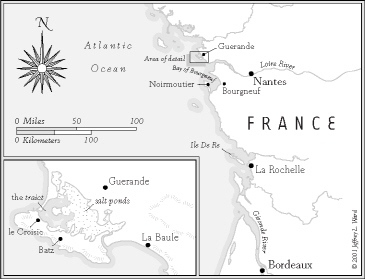

fishing nations of northern Europe wanted to participate in the new, rapidly growing, extremely profitable salt cod market. They had the cod but they needed salt, and the Vikings may have been pivotal in solving this problem as well. One of the first Viking bases in the Loire was the island of Noirmoutier. One third of this long thin island, barely detached from the mainland of France at the estuary of the Loire, is a natural tidal swamp, which strong tides periodically flood with a fresh supply of seawater. The Vikings had long been interested in the use of solar evaporation in making sea salt. Traces of such Viking operations in the seventh century have been found in Normandy. But the northern climate would have made these saltworks unproductive. The climate has too much rainfall and not enough sunlight. It is not known exactly when Noirmoutier, the nearby mainland marshes of Bourgneuf and Guérande, and Ile de Ré, an island about sixty miles to the south, started building systems of artificial ponds, instead of relying on single pond evaporation. As with sharing their shipbuilding skills with the Basques, no record exists of the Vikings teaching artificial pond techniques, but it is known that at the time of their arrival, production greatly increased, that the ponds were built sometime in the ninth or tenth century, and that the Vikings had seen successive artificial pond systems in southern Spain. Since Guérande is in Celtic Brittany, Breton historians with a nationalist streak reject the Viking theory, preferring to believe that Celts originated the idea, which is also possible. It is more certain that the Vikings were the first to trade the salt of this area to the Baltic and other northern nations, establishing one of the most important salt routes of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

As Europeans began to recognize that the natural solar evaporation of seawater was the most cost-effective way to produce salt, this area on the southern side of the Brittany peninsula, the Bay of Bourgneuf, became a leading salt center. This bay was the most northerly point in Europe with a climate suited to solar-evaporated sea salt. The bay also had the advantage of being located on the increasingly important Atlantic coast and was connected to a river that could carry the salt inland. Guérande on the north side of the mouth of the Loire River, Bourgneuf on the southern side and the island of Noirmoutier facing them, became major sea salt-producing areas.

O

NE GROUP OF

Vikings remained in Iceland, becoming the Icelanders. A second group remained in the Faroe Islands. The main body of Vikings were given lands in the Seine basin in exchange for protecting Paris. They settled into northern France and within a century were speaking a dialect of French and became known as the Normans. Soon the Vikings had vanished.

Meanwhile, Basque ships sailed out with their enormous holds full of salt and returned with them stacked high with cod. They dominated the fast-growing salt cod market, just as they had the whale market, and they used their whale-hunting techniques as a model for cod fishing. They were efficient fishermen, loading huge ships with small rowboats and sailing long distances, launching the rowboats when they reached the cod grounds. This became the standard technique for Europeans to fish cod and was used until the 1950s, when the last few Breton and Portuguese fleets converted to engine power and dragging nets.

Others besides the Basques caught cod in the Middle Ages—the fishermen of the British Isles, Scandinavia, Holland, Brittany, and the French Atlantic—but the Basques brought back huge quantities of salted cod. The Bretons began to suspect that the Basques had found some cod land across the sea. By the early fifteenth century, Icelanders saw Basque ships sailing west past their island.

Did the Basques reach North America before John Cabot’s 1497 voyage and the age of exploration? During the fifteenth century, most Atlantic fishing communities believed that they had. But without physical proof, many historians are skeptical, just as they were for many years about the stories of Viking travels to North America. Then in 1961, the remains of eight Viking-built turf houses dating from

A.D.

1000 were found in Newfoundland in a place called L’Anse aux Meadows. In 1976, the ruins of a Basque whaling station were discovered on the coast of Labrador. But they dated back only to 1530. Like Marco Polo’s journey to China, a pre-Columbian Basque presence in North America seems likely, but it has never been proved.

F

ISHERMEN ARE SECRETIVE

about good fishing grounds. The Basques kept their secret, and others may have also. Some evidence suggests that a British cod fishing expedition had gone to North America more than fifteen years before Cabot. The Portuguese believe their fishermen also reached North America before Cabot.

Explorers, on the other hand, were in the business of announcing their discoveries. And they said the cod fishing in the New World was beyond anything Europeans had ever seen. Raimondo di Soncino, the duke of Milan’s envoy to London, sent the duke a letter saying that one of Cabot’s crew had talked of lowering baskets over the side and scooping up codfish.

After Cabot’s voyage, large-scale fishing expeditions to North America were launched from Bristol, St.-Malo on the Brittany peninsula, La Rochelle on the French Atlantic coast, the Spanish port of La Coruña in Celtic Galicia, and the Portuguese fishing ports. Added to this were the many Basque towns that had long been whale and cod ports, including Bayonne, Biarritz, Guéthary, St.-Jean-de-Luz, and Hendaye on the French side, Fuenterrabía, Zarautz, Guetaria, Motrico, Ondarroa, and Bermeo on the Spanish side. On board each of these hundreds of vessels, ranked as a senior officer, was a “master salter” who made difficult decisions about the right amount of salting and drying and how this was done. Both under- and oversalting could ruin a catch.

In the Middle Ages, salt already had a wide variety of industrial applications besides preserving food. It was used to cure leather, to clean chimneys, for soldering pipes, to glaze pottery, and as a medicine for a wide variety of complaints from toothaches, to upset stomachs, to “heaviness of mind.” But the explosion in the salt cod industry after Cabot’s voyage enormously increased the need for sea salt, which was believed to be the only salt suitable for curing fish.

For the Portuguese, the salt cod trade meant growth years for fishing and salt making. Lisbon was built on a large inlet with a small opening. Aviero, farther up on the marshy shores of the inlet, was an ideal salt-making location. It had been the leading source of Portuguese salt since the tenth century. But with the growing demand, the saltworks at Setúbal, built in a similar inlet just south of the capital, became Portugal’s leading supplier. Setúbal’s salt earned a reputation throughout Europe for the dryness and whiteness of its large crystals. It was said to be the perfect salt for curing fish or cheese.

Other books

Entropy Risen (The Syker Key Book 3) by Fransen, Aaron Martin

Armies of Light and Dark by Babylon 5

Killer Takes All by Erica Spindler

Xcite Delights Book 1 by Various

1. Earth Pack Rules: Her Alpha Lovers Part One by Michele Bardsley

Silk on the Skin: A Loveswept Classic Romance by Cajio, Linda

Stalin's Children by Owen Matthews

The Distant Home by Morphett, Tony

LoversFeud by Ann Jacobs

Blind to Betrayal: Why We Fool Ourselves We Aren't Being Fooled by Freyd, Jennifer, Birrell, Pamela