Salt (16 page)

Prosciutto makers used salt from Salsomaggiore, but cheese makers used sea salt supplied either by Venice or by Genoa. In the sixteenth century, the powerful Farnesi family arranged 5,000 mule caravans to carry salt from Genoa’s Ligurian coast, known today as the Italian Riviera. Caravans from Genoa carried salt inland to Piacenza, where it was placed on river barges and carried down the Po to Parma. Unlike in Africa or ancient Rome, no single salt route was established. Each caravan had to devise a route based on arrangements with the feudal lords along the way.

Inland cities of the Po Valley such as Parma had their own salt policies and derived revenue from the import of Venetian or Genoese salt, a cost which was passed on to their local consumers. This created a permanent salt contraband trade along the back routes between Genoa, Piacenza, Parma, Reggio, Bologna, and Venice.

In exchange for the salt, the Po Valley traded its salt products: salami, prosciutto, and cheese. It also traded its famous soft wheat for salt. The trade changed with the times. In the eighteenth century, when the Bourbons ruled Parma, they traded their French luxury items for salt, but they also exchanged galley slaves for salt with Genoa, which needed galley slaves for its expanding trade empire. In Parma, a ten-year prison sentence could be reduced to five years as a galley slave on a Genoese ship. But most of these slaves lived only two years, which caused a constant need for replacements.

I

N THE FIFTH

century

B.C.

, before Genoa was Roman, it was the thriving port of a local people called the Ligurians. It was taken by Rome, by Carthage, by Rome again, by Germanic tribes, by Muslims. Finally, in the twelfth century it became, like Venice, an independent city-state dedicated to commerce.

Genoa bought salt from Hyères near Toulon in French Provence. The name Hyères means “flats” and probably refers to salt flats, because as far back as is known, salt was produced in this place. But in the twelfth century, Genoese merchants turned Hyères into an important producer by building a system of solar evaporation ponds. Genoa’s success in Hyères led to the decline of Pisa’s Sardinian salt trade. Genoese salt merchants then moved into Sardinia, developed the saltworks of Cagliari, again building a system of evaporation ponds, and made Sardinia one of the largest salt producers in the Mediterranean.

The Genoese also bought salt from Tortosa on the Mediterranean coast of Iberia, south of Barcelona. Tortosa is at the mouth of the Ebro River, which gave it a water connection from Catalonia through Aragon to Basque country—a waterway through the most economically developed parts of the Iberian Peninsula. Tortosa had been a salt producer for the Moors, but by the twelfth century, when Genoa became involved, it was one of the principal suppliers of the port of Barcelona as well as Aragon.

In the mountainous interior of Catalonia, the dukes of Cardona were not happy to see the Genoese selling salt in Barcelona. In 886, a man about whom little is known except possibly his appearance, Wilfredo the Hairy rebuilt an abandoned eighth-century castle on a mountain fifty miles inland from Barcelona. Alone on what was then a distant mountaintop, the highest peak in a rugged, sparsely populated area, he could peer from the thick stone ramparts at his prize possession, the source of his wealth, the next mountain.

This next mountain was striped in pattern and colors so lively, it was almost dizzying to look at it—salmon pink rock with white, taupe, and bloodred stripes. It was all salt. Since salt is soluble in water, elongated facets were cut into the mountain by each rainfall. Inside the mine the pink-striped shafts were ornamented by snow-white crystal stalactites, long dangling tentacles where the salt had sealed over dripping rainwater from fissures above. The salt mountain was by a winding river, a shallow tributary of the Ebro. Rich green plains and gentle terraced slopes were farmed in the distance, and on the horizon, the snow-crested peaks of the Pyrenees could be seen.

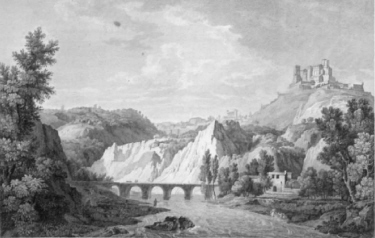

An engraving of Cardona from

Voyage pittoresque et historique de l’Espagne (1807–1818).

The castle is on the highest hill, the salt mountain below, by the river. The town where the salt workers lived can be seen in the distance.

Biblioteca de Catalunya

The lords who occupied the castle were the owners of the mountain. A dank brown village of salt workers sprang up on an adjacent mountain. On Thursdays, the salt workers were allowed to take salt for themselves. Starting at least in the sixteenth century, salt workers carved figurines, often religious, from the rock, which has the appearance of pink marble. Soft and soluble, rock salt is easy to carve and even easier to polish.

Even in the area around the salt mountain, all but the top two to three feet of soil is salt, and the white powder leaches to the surface when it rains. There is evidence that people took salt from here as far back as 3500

B.C.

Prehistoric stone tools have been found—six-inch-long black rocks with one end serving as a pick and the other as a scraping tool.

The first written record of salt in Cardona is from the Romans, who usually favored sea salt but considered Cardona’s rock salt to be of high quality. In the ninth century, the dukes of Cardona, along with the other feudal lords of the Catalan-speaking area, were united under the counts of Barcelona. Catalonia, with its own Latin-based language, became an important commercial power whose territory extended along the Mediterranean coast from north of the Pyrenees to southern Spain.

Cardona was known in medieval Catalonia as an ideal source of salt for making hams and sausages. From the capital, the port of Barcelona, Cardona salt was exported to Europe and became one of the leading rock salts in the Middle Ages. But by the twelfth century, Genoa could bring salt by sea to Barcelona less expensively than the dukes of Cardona could bring it across the fifty-mile land route. As Cardona salt merchants started to lose their Barcelona market, they too began selling their salt to the Genoese.

A

FTER 1250, GENOA

went even farther into the Mediterranean, buying salt in the Black Sea, North Africa, Cyprus, Crete, and Ibiza—many of the same saltworks that Venice was trying to dominate. Genoa built Ibiza into the largest salt producer in the region.

Salt was the engine of Genoese trade. With the salt the Genoese bought, they made salami, which was sold in southern Italy for raw silk, which was sold in Lucca for fabrics, which were sold to the silk center of Lyon. Genoa competed with Venice not only for salt but for the other cargoes that were exchanged for salt, such as textiles and spices.

The Genoese were pioneers in maritime insurance, banking, and the use of huge Atlantic-sized ships, which they bought or leased from the Basques, in Mediterranean trade. These ships, with their vast cargo holds, had room for salt on a return voyage. Wherever they went for trade, they made a point of getting control of a saltworks at which to load up for the return trip.

But Venice was winning the competition because of a more cohesive political organization and because of its system of salt subsidies. When this salt competition led to a war in 1378–80, known as the War of Chioggia, Venice’s ability to convert its commercial fleet into warships proved decisive. Venice defeated Genoa, its only major competitor for commercial dominance of the Mediterranean.

Yet among those who finally undid the maritime empire of Venice were two Genoese—Cristoforo Colombo and Giovanni Caboto. Neither sailed on behalf of Genoa, and Caboto actually became a Venetian citizen. The beginning of the end came in 1488 when the Portuguese captain Bartolomeu Dias rounded Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. In 1492, Columbus, in search of another route to India in the opposite direction, began a series of voyages for Spain, which opened up trans-Atlantic trade carrying new and valuable spices. Then in 1497, Caboto, the Genoese turned Venetian, sailed for England as John Cabot, again looking for a route to India, and told the world about North America and its wealth of codfish. Worst of all, that same year, another Portuguese, Vasco da Gama, sailed around Africa to India and returned to Portugal two years later. Not only were Atlantic ports now needed for trade with the newly found lands, but the Portuguese had opened the way from Atlantic ports to the Indian Ocean and the spice producers. Now the Atlantic, and not the Mediterranean, was the most important body of water for trade.

After the fifteenth century, the Mediterranean ceased to be the center of the Western world, and Venice’s location was no longer advantageous. Yet it stubbornly held to its independence and so declined with the Mediterranean.

Genoa succumbed to the new reality, and during Spain’s golden age, the Genoese served as the leading bankers and financiers of that expanding Atlantic power. Because of this, Genoa has endured as a commercial center and is today a leading Mediterranean port, though the Mediterranean is no longer a leading sea.

The Glow of Herring and the Scent of Conquest

At the time when Pope Pius VII had to leave Rome, which had been conquered by revolutionary French, the committee of the Chamber of Commerce in London was considering the herring fishery. One member of the committee observed that, since the Pope had been forced to leave Rome, Italy was probably going to become a Protestant country. “Heaven help us,” cried another member. “What,” responded the first, “would you be upset to see the number of good Protestants increase?” “No,” the other answered, “it isn’t that, but suppose there are no more Catholics, what shall we do with our herring?”

—Alexandre Dumas,

Le grand dictionnaire de cuisine,

1873

Other books

Operation Napoleon by Arnaldur Indriðason

According to the Pattern by Hill, Grace Livingston

Blue Moon II ~ This is Reality by A.E. Via

Last in a Long Line of Rebels by Lisa Lewis Tyre

Slapping Leather by Holt, Desiree

A Fresh Start by Martha Dlugoss

Hare Moon by Carrie Ryan

Alienated by Milo James Fowler

Adapting Desires (Endangered Heart Series Book 3) by Lance, Amanda

The Ex Factor: A Novel by Whitaker, Tu-Shonda