Salt (15 page)

On the rich plains of Emilia-Romagna, off of the great Roman road, are the ruins of a Roman city named Veleia. Historians have puzzled over Veleia because the Romans had a clear set of criteria for the sites of their cities and Veleia does not fit them. Not only is it too far from the road, it is on the cold windward side of a mountain. But it has one thing in common with almost every important city in Italy: It is near a source of salt. Veleia was built over underground brine springs, which is why it came to be known as the big salt place, Salsomaggiore.

The earliest record of salt production in Veleia dates from the second century

B.C.

Like many other saltworks, it was abandoned after the fall of the Roman Empire. Charlemagne, the conquering Holy Roman emperor who, like the Romans before him, had an army that needed salt, started it up again. The name Salso first appears on an 877 document.

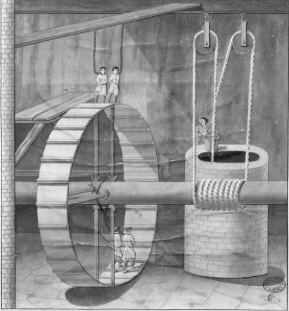

In ancient times the brine wells had a huge wheel with slats inside and out for footing. Two men, chained at the neck, walked inside on the bottom, stepping from slat to slat, and two other men, also chained at the neck, did the same on the outside on top. The wheel turned a shaft that wrapped a rope, which hoisted buckets of brine. The brine was then boiled, which meant that a duke or lord who wished to control the brine wells had to also control a wide area of forest to provide wood for fuel.

Engraving from the late Middle Ages of a wheel powered by prisoners used to pump brine at Salsomaggiore.

State Archives, Parma

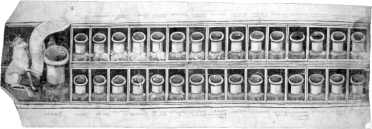

Starting in the eleventh century, the Pallovicino family controlled the wells and the region. But in 1318, the city of Parma took over thirty-one Pallovicino wells. The event was considered important enough to be recorded in a fresco in the city palace. He who controlled the brine wells at Salsomaggiore controlled the region, and the takeover of these thirty-one brine wells marked the transfer of power from feudal lord to city government.

I

N THE SEVENTH

and eighth centuries, before Charlemagne restarted the wells at Salsomaggiore, sailors brought salt from the Adriatic to Parma. For this labor they could receive either money or goods, including Parma’s most famous salt product, ham—

prosciutto di Parma

.

A fresco on a wall of the Parma city palace that recorded the city’s acquisition of thirty-one wells. The bull is the symbol of Parma. The fresco was destroyed when a tower collapsed on the palace in the seventeenth century.

State Archive, Parma

Parma was a good place to make ham because before the sea air reaches Parma it is caught in the mountain peaks, producing rain and drying out the wind that comes down to the plain. That dry wind is needed for aging the salted leg in a place dry enough to avoid rotting. The drying racks for the hams were always arranged east to west to best use the wind.

Bartolomeo Sacchi, a native of the Po Valley town of Cremona, who became a well-known fifteenth-century author under the pen name Platina, gave blunt and easily followed instructions for testing the quality of a ham:

Stick a knife into the middle of a ham and smell it. If it smells good, the ham will be good; if bad, it should be thrown away.

The sweet-smelling ham of Parma earned a reputation throughout Italy that was credited not only to the region’s dry wind but to the diet of their pigs, a diet which came from the local cheese industry. The Po Valley, where butter is preferred to olive oil, is Italy’s only important dairy region. According to Platina, this was more a matter of necessity than taste.

Almost all who inhabit the northern and western regions use it [butter] instead of fat or oil in certain dishes because they lack oil, in which the warm and mild regions customarily abound. Butter is warm and moist, nourishes the body a good deal and is fattening, yet the stomach is injured by its frequent use.

Notice that Platina listed butter’s fattening quality as a virtue, although he was a writer who tended to look for the unhealthy in food including salt, about which he wrote:

“It is not good for the stomach except for arousing the appetite. Its immoderate use also harms the liver, blood, and eyes very much.”

And he was not much more sanguine about the pride of his native region, aged cheese.

Fresh cheese is very nourishing, represses the heat of the stomach, and helps those spitting blood, but it is totally harmful to the phlegmatic. Aged cheese is difficult to digest, of little nutriment, not good for stomach or belly, and produces bile, gout, pleurisy, sand grains, and stones. They say a small amount, whatever you want, taken after a meal, when it seals the opening of the stomach, both takes away the squeamishness of fatty dishes and benefits digestion.

The difference between fresh cheese and aged cheese is salt. Italians call the curds that are eaten fresh before they begin to turn sour,

ricotta,

and it is made all over the peninsula in much the same way. But once salt is added, once cheese makers cure their product in brine to prevent spoilage and allow for aging, then each cheese is different.

The origin of cheese is uncertain. It may be as old as the domestication of animals. All that is needed for cheese is milk and salt, and since domesticated animals require salt, that combination is found most everywhere. Just as goats and sheep were domesticated earlier than cattle, it is thought that goat’s and sheep’s milk cheeses are much older ideas than cow’s milk cheese. The habit of carrying liquids in animal skins may have caused the first cheeses since milk coming in contact with an animal skin will soon curdle.

Soon, herders, probably shepherds, found a more sophisticated variation known as rennet. Rennet contains rennin, an enzyme in the stomach of mammals which curdles milk to make it digestible. Usually, rennet is made from the lining of the stomach of an unweaned young animal because unweaned animals have a higher capacity to break down milk. Here, too, salt played a role because these stomach linings were preserved in salt so that rennet from calving season would be usable throughout the year.

The Romans made a tremendous variety of cheeses, with differences not only from one area to another but from one cheese maker to another in the same place and possibly even from one batch to another from the same cheese maker.

Parmesan cheese, now called

Parmigiano-Reggiano

because it is made in the green pastureland between Parma and Reggio, may have had its origins in Roman times, but the earliest surviving record of a Parma cheese that fits the modern description of Parmigiano-Reggiano is from the thirteenth century. It was at this time that marsh areas were drained, irrigation ditches built, and the acreage devoted to rich pastureland greatly expanded. About the same time, standards were established by local cheese makers that have been rigidly followed ever since. Parma cheese earned an international reputation and became a profitable export, which it remains. Giovanni Boccaccio, the fourteenth-century Florentine father of Italian prose, mentions it in

The Decameron

. In the fifteenth century, Platina called it the leading cheese of Italy. Samuel Pepys, the seventeenth-century English diarist, claimed to have saved his from the London fire by burying it in the backyard. Thomas Jefferson had it shipped to him in Virginia.

In Parma, the production of cheese, ham, butter, salt, and wheat evolved into a perfect symbiotic relationship. The one thing the Parma dairies produced very little of was and still is milk. Just as the Egyptians millennia before had learned that it was more profitable to make salt fish than sell salt, the people of the Po determined that selling dairy products was far more profitable than selling milk.

The local farmers milked their cows in the evening, and this milk sat overnight at the cheese maker’s. In the morning, they milked them again. The cheese makers skimmed the cream off the milk from the night before, and the resulting skim milk was mixed with the morning whole milk. The skimmed-off cream was used to make butter.

Heating the mixed milk, they added rennet and a bucket of whey, the leftover liquid after the milk curdled in the cheese making the day before. They then heated the new mixture to a higher temperature, still well below boiling, and left it to rest for forty minutes.

At this point the milk had curdled, leaving an almost clear, protein-rich liquid, and this whey was fed to pigs. It became a requirement of prosciutto di Parma that it be made from pigs that had been fed the whey from Parmesan cheese. Less choice parts of pigs fed on this whey qualified to be sent to the nearby town of Felino, where they were ground up and made into salami. (The word

salami

is derived from the Latin verb

to salt.

)

The cheese makers also mixed whey with whole milk once a week to make fresh ricotta. By tradition ricotta was made on Thursday so that the cheese would be ready for Sunday’s traditional

tortelli d’erbette. Erbette

literally means “grass,” but in Parma it is also the name of a local green similar to Swiss chard. Tortelli d’erbette is a ravioli-like pasta stuffed with ricotta, Parmigiano cheese, erbette, salt, and two spices that were a passion in the thirteenth century and highly profitable cargo for the ships of both Venice and Genoa: black pepper and nutmeg. Tortelli d’erbette was and still is served with nothing but butter and grated Parmigiano cheese.

Before it succumbed to being heavily salted, butter was a rare delicacy. That was especially true in the Po Valley at the southern extreme of butter’s range in Europe. In the Parma area, butter was a privilege of the cheese masters—theirs to distribute or sell, generally at high prices. Butter is still sold in the Parmigiano-Reggiano area by cheese masters.

Stuffed pasta in butter sauce worked particular well in this region where the local wheat was soft, different from the rest of Italy, and produced a pasta that, when mixed with eggs, was rich and supple when fresh, but brittle and unworkable when dried. Dried pasta, like olive oil, belonged to the rest of Italy.

Each creamery had a cheese master whose hands reached into the copper vats and ran through the whey with knowing fingers, scooping up and pressing the curds as they were forming. When he said the cheese was done, a cheesecloth was put into the vat, and under his direction the corners of the cloth were lifted, hoisting from the whey more than 180 pounds of drained curd. While the others struggled to suspend the mass in the cheesecloth, only the cheese master was allowed to take the big, flat, two-handed knife and divide the mass in two.

The two cheeses were left one day in cheesecloth and then put in wooden molds. The Latin word for a wooden cheese mold,

forma,

is the root of the Italian word for cheese,

formaggio

. After at least three days, the ninety-pound cheeses were floated in a brine bath turned every day. The aging of cheese is a matter of its slow absorption of salt. It takes two years for the salt to reach the center of a wheel of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. After that the cheese begins to dry out. So these cheeses have always had one year of life between when they are sold and when they are considered too hard and dry, even too salty. Platina’s admonition about aged cheese may have been a concern about overly aged cheese.

Other books

Man of the Hour by Diana Palmer

Paper Chains by Nicola Moriarty

Soul Thief (Dark Souls) by Hope, Anne

The Trafficked by Lee Weeks

The Marriage Market by Spencer, Cathy

The Best Man by Ella Ardent

The Breaker's Resolution: (YA Paranormal Romance) (Fixed Points Book 4) by Conner Kressley

Gone Missing (Kate Burkholder 4) by Castillo, Linda

Vanished Without A Trace by Nava Dijkstra

A Nomadic Witch (A Modern Witch Series: Book 4) by Geary, Debora